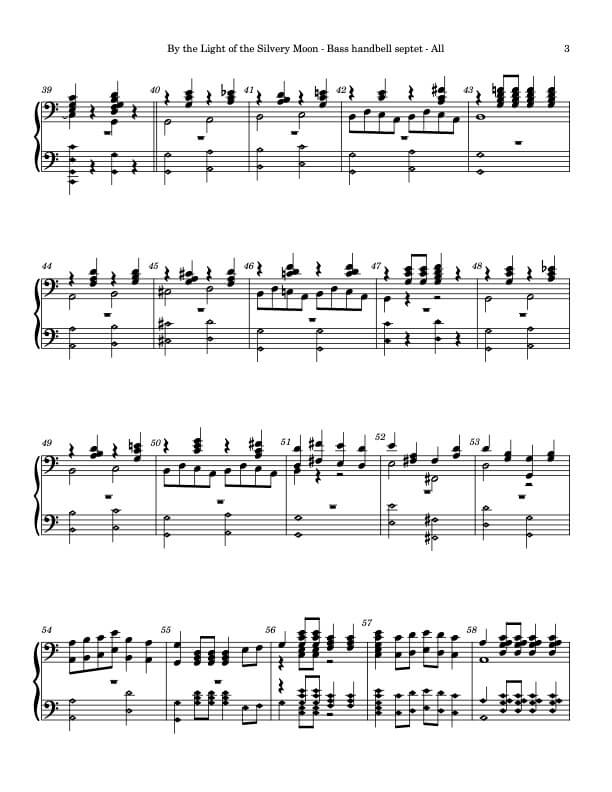

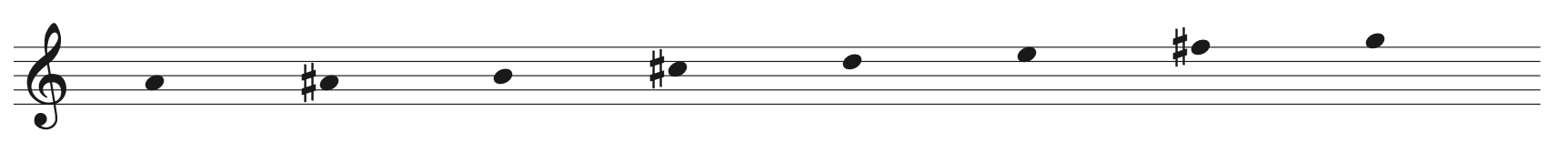

I’m a “bass ringing specialist”. The simple explanation of that phrase is that some people think that I’m reasonably proficient at ringing bass bells. I realize that still requires a bit of clarification, because the bass clef in modern handbell music tops out at C5 (which is written as a middle C on the handbell grand staff). Some of those “bass bells” are a bit on the small side, since C5 weighs a bit over one pound (comparable to a standard softball).

The bells grow in size more or less exponentially as you go down the scale. C4 weighs about three pounds and C3 weighs seven to eleven pounds, depending on manufacturer). These weights are for bronze handbells, and so the bronze C2 weighs between fifteen and twenty pounds, depending on manufacturer. There’s a huge weight improvement for Malmark aluminum bells; the C2 of this type weighs just nine pounds – but the aluminum casting is a lot larger than the corresponding bronze one, so the actual effort of ringing each bell is approximately equivalent because of the tradeoff between raw mass and weight distribution.

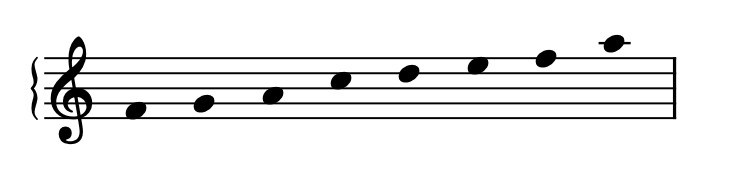

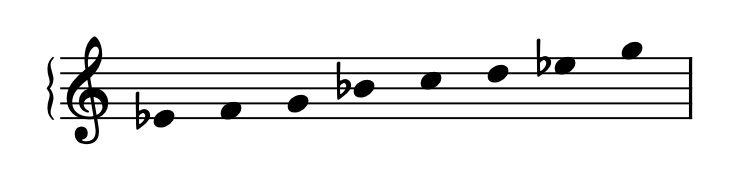

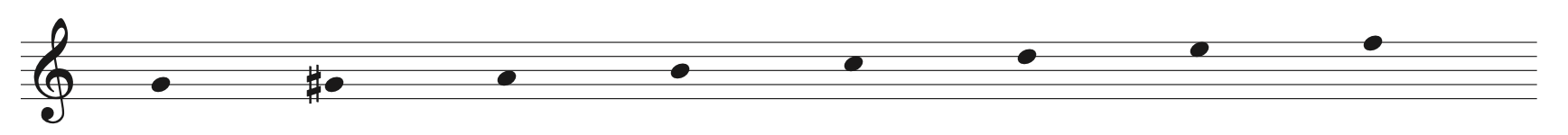

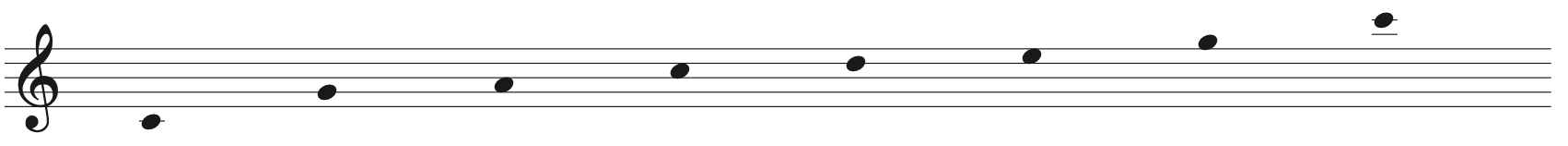

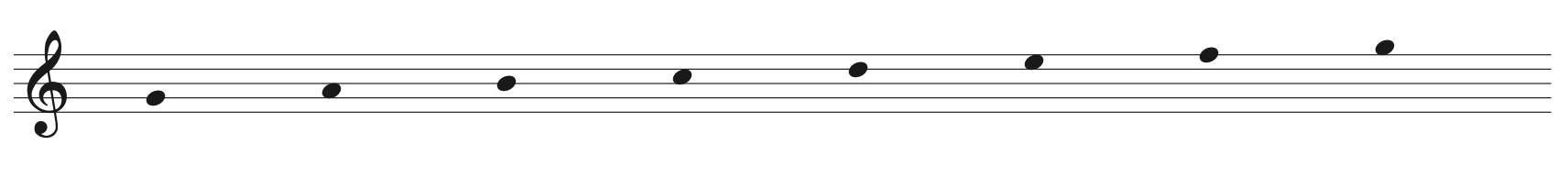

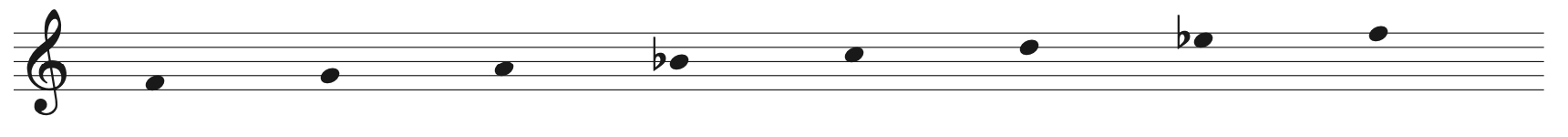

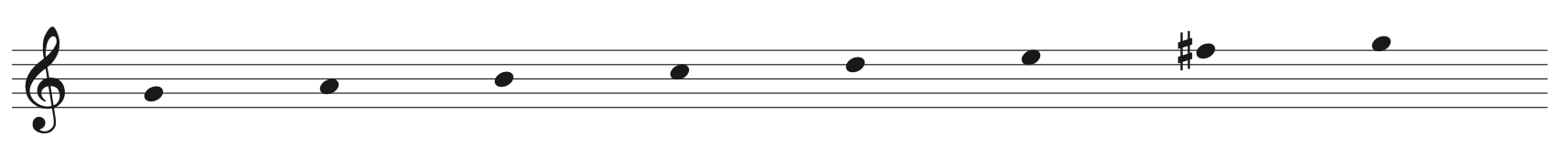

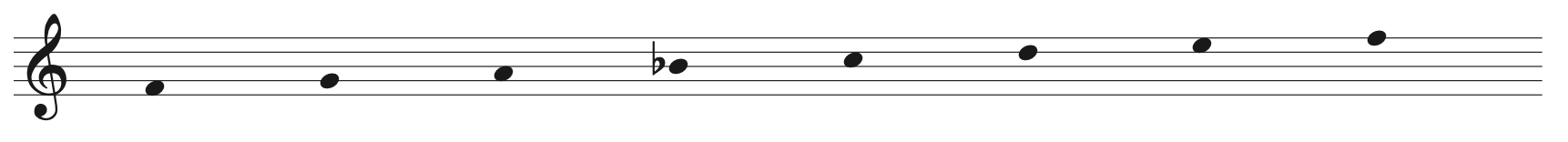

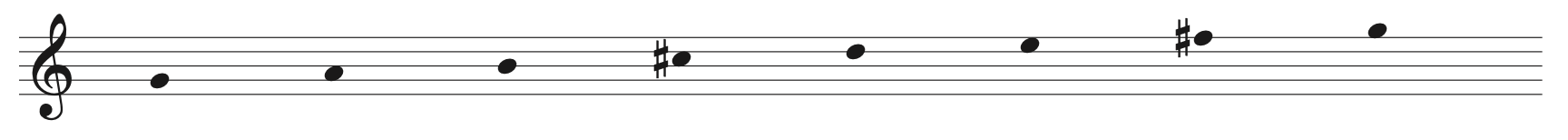

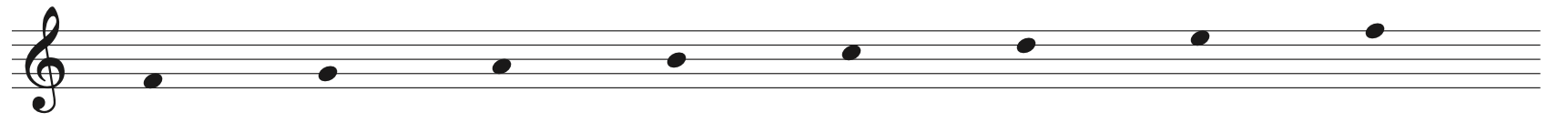

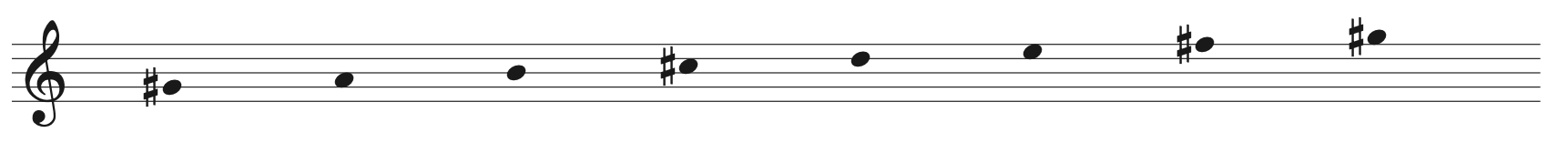

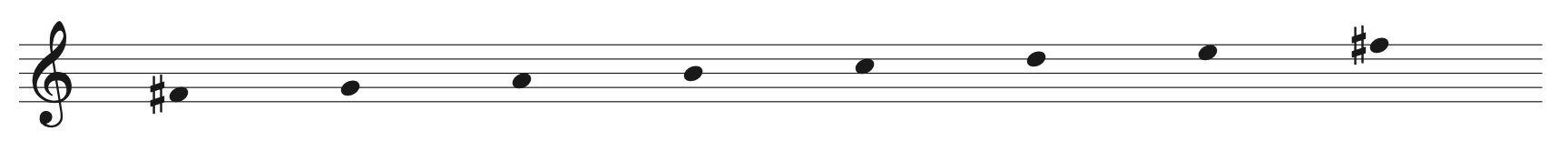

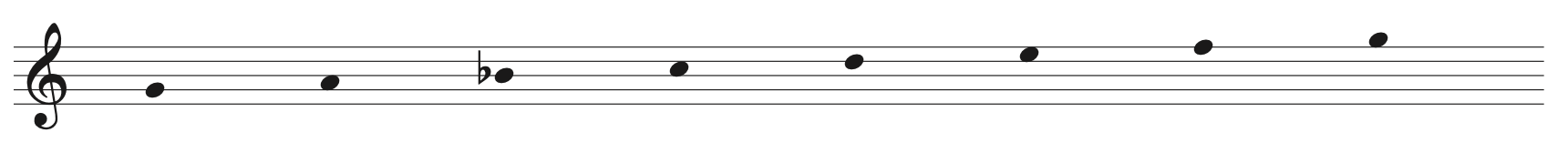

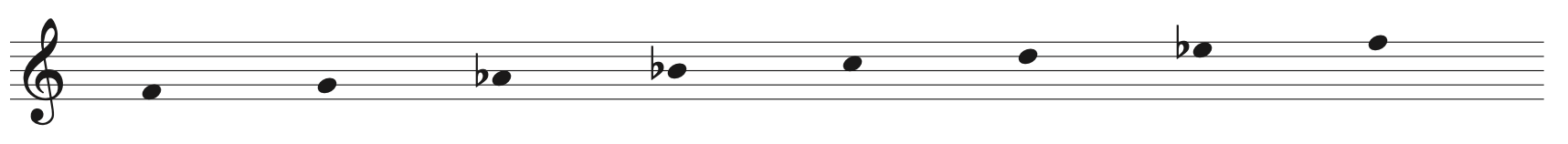

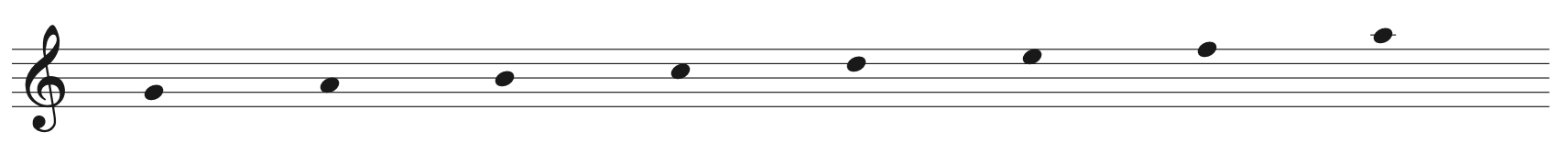

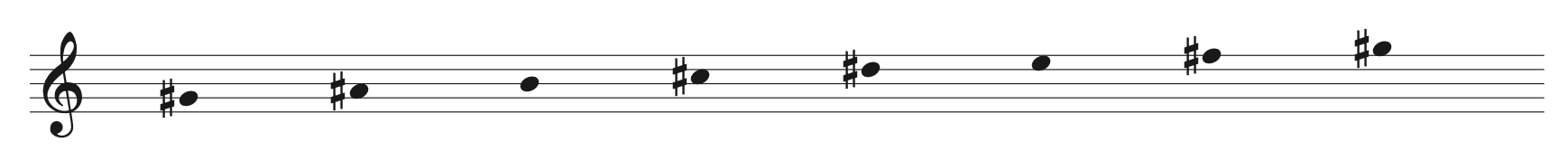

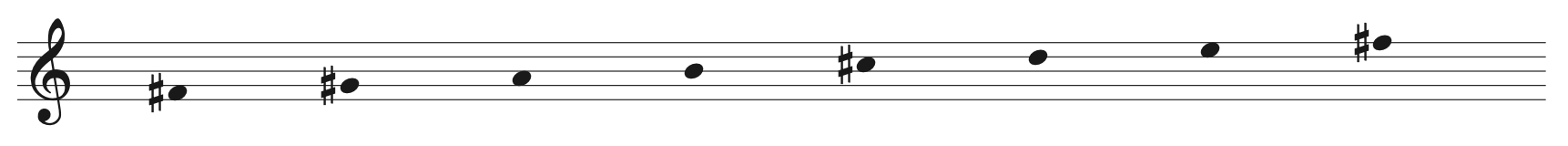

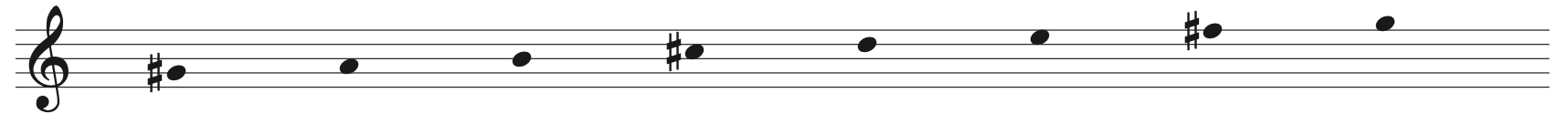

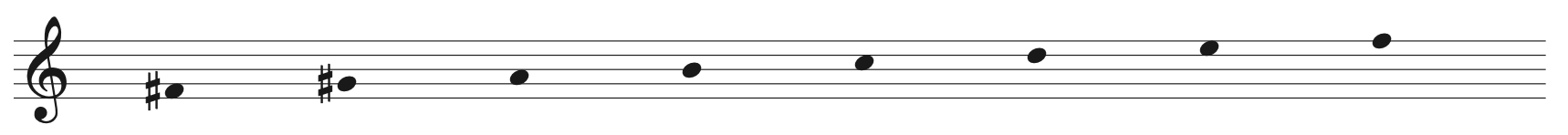

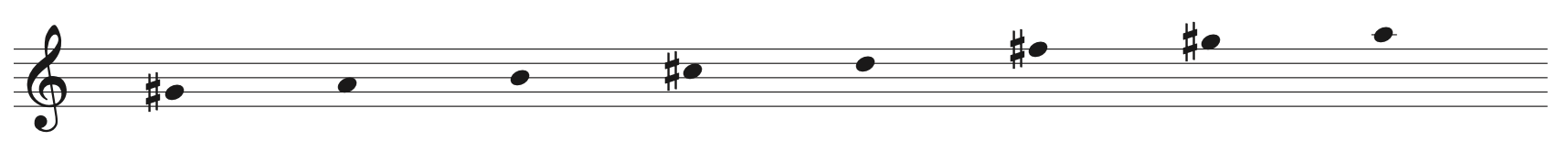

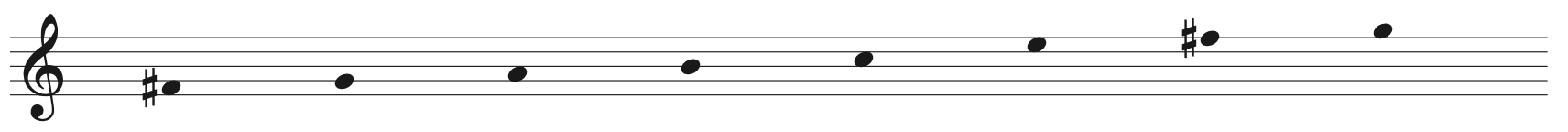

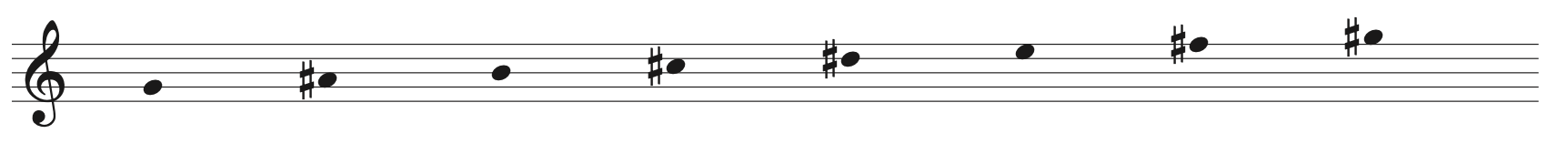

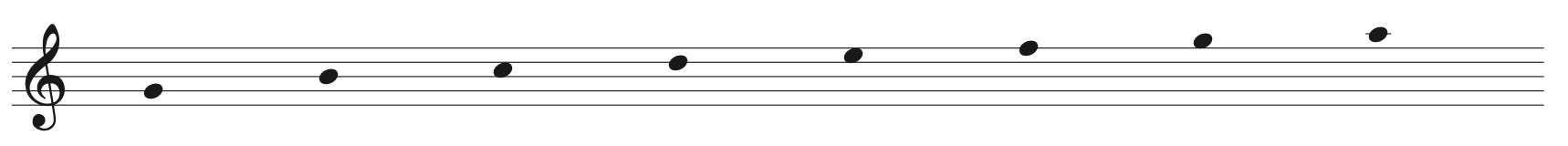

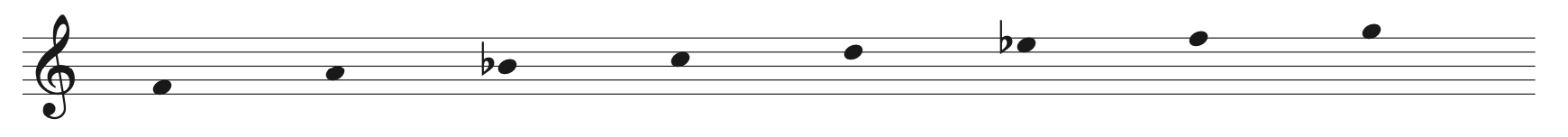

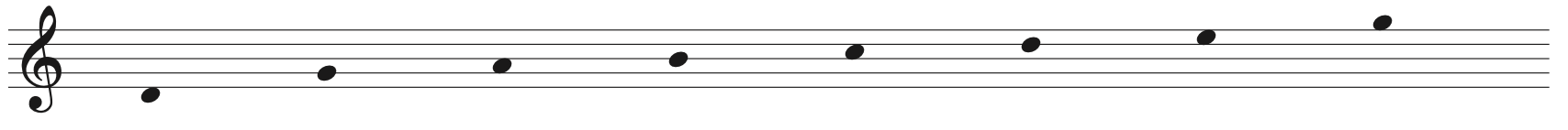

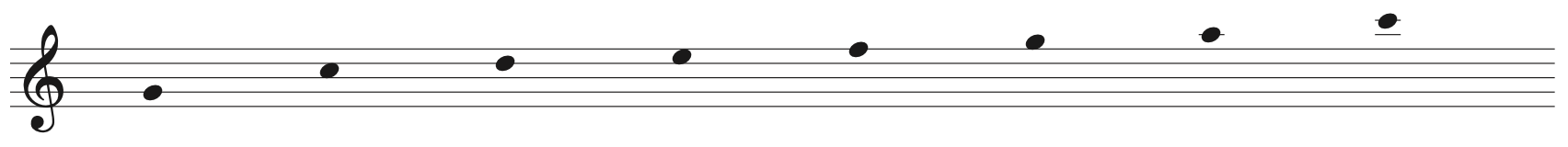

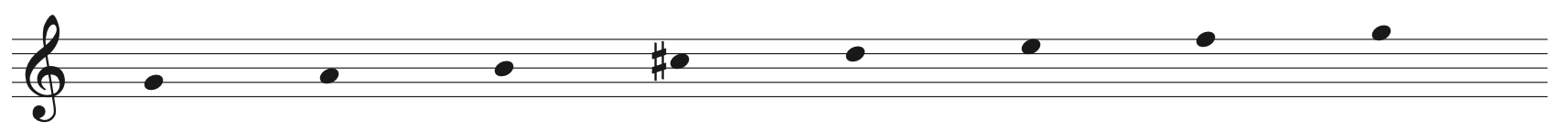

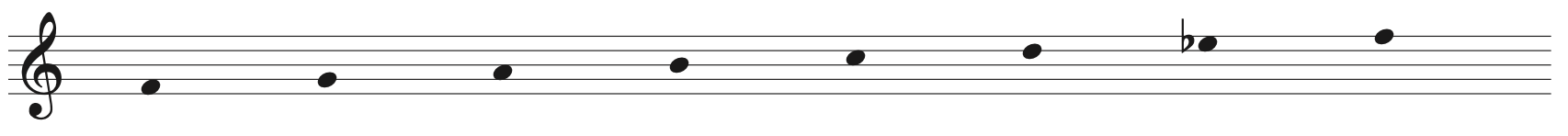

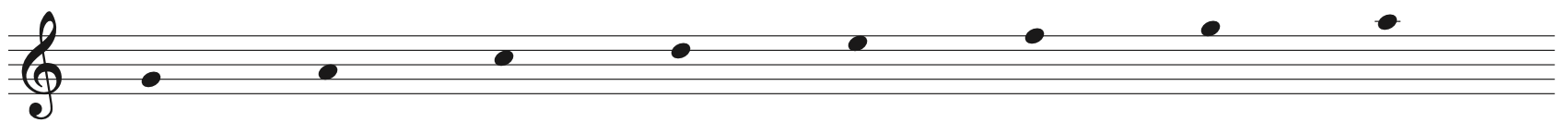

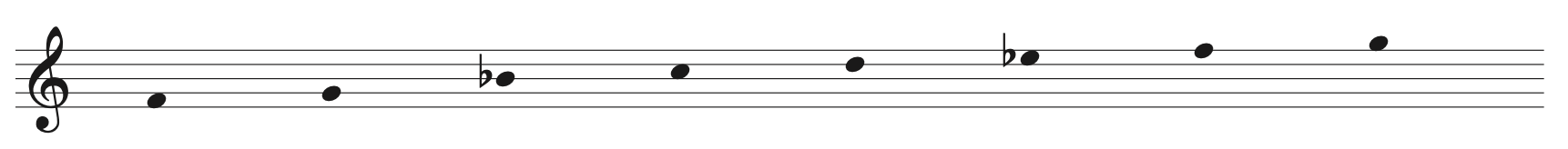

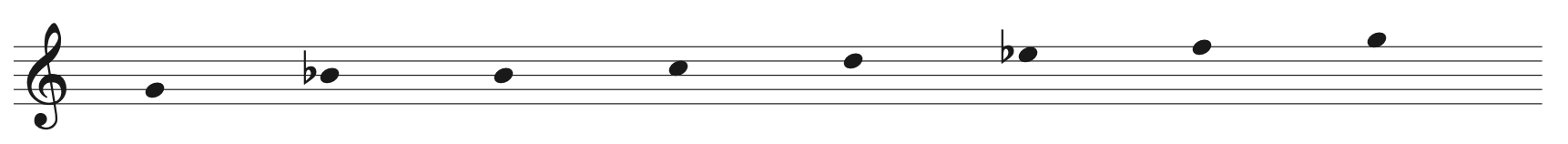

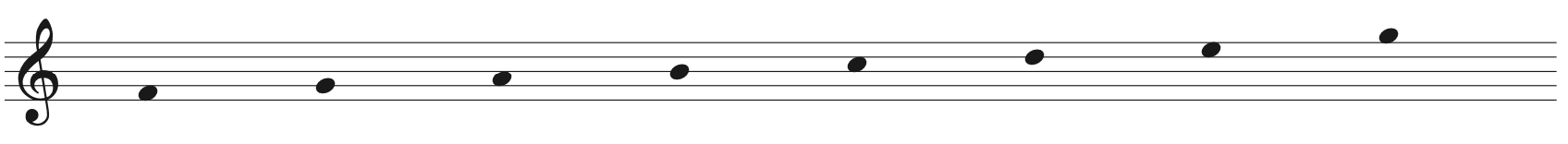

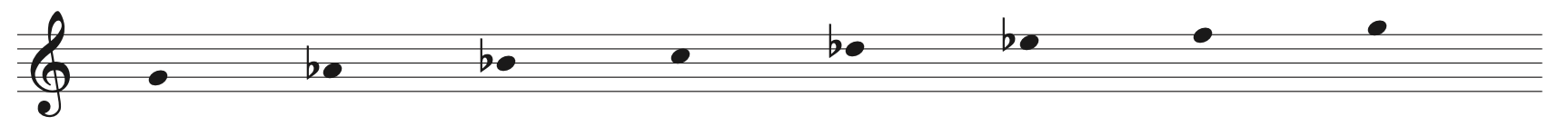

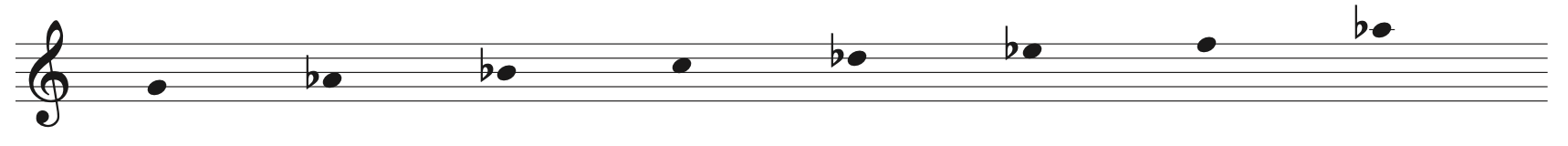

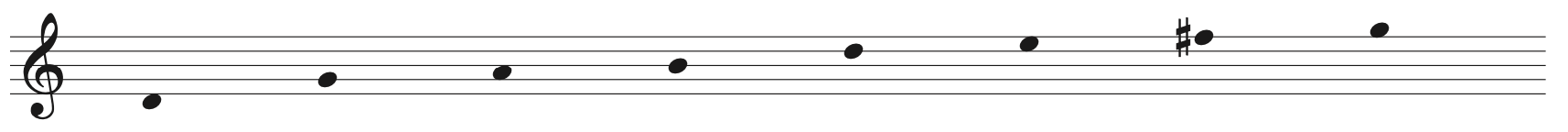

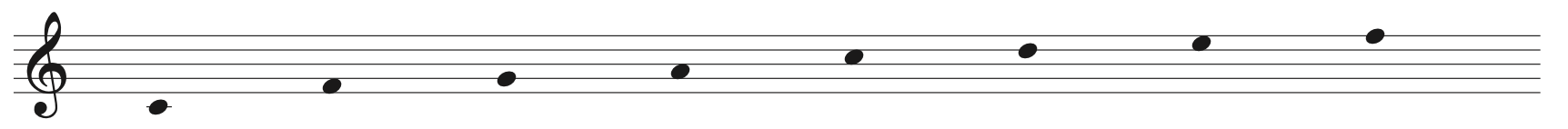

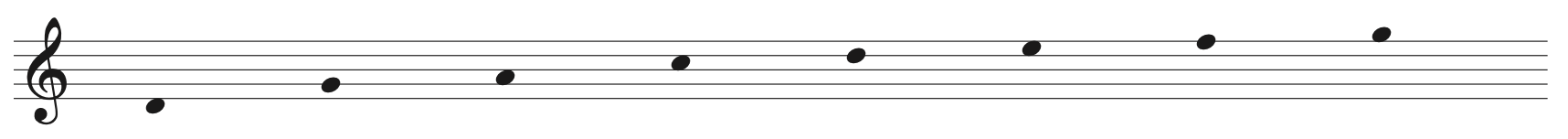

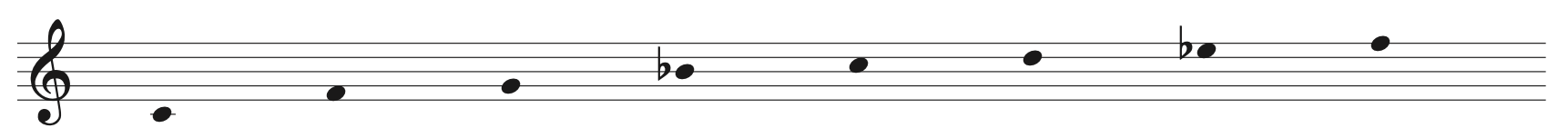

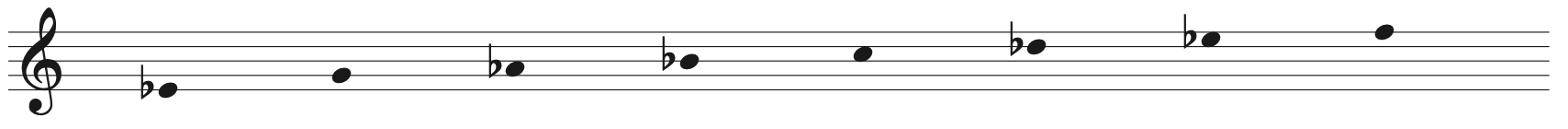

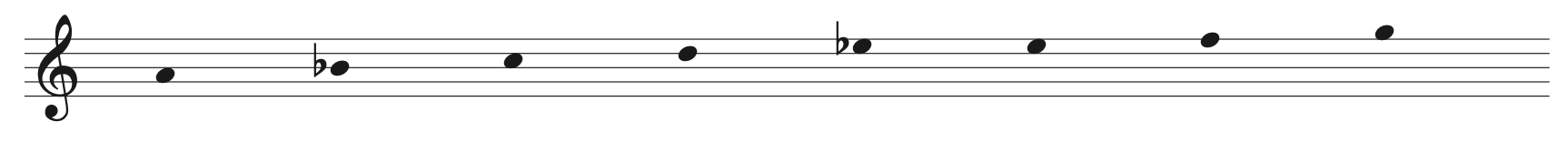

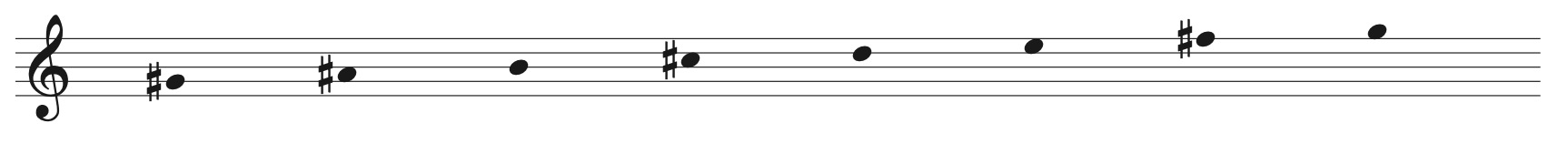

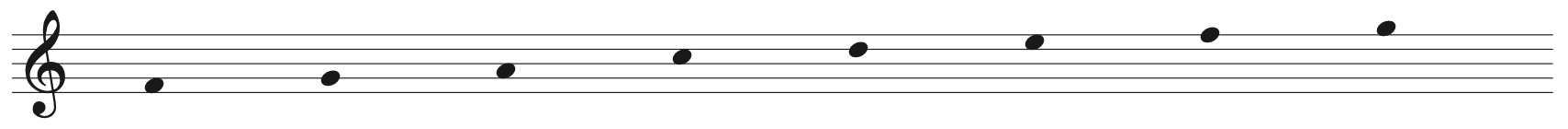

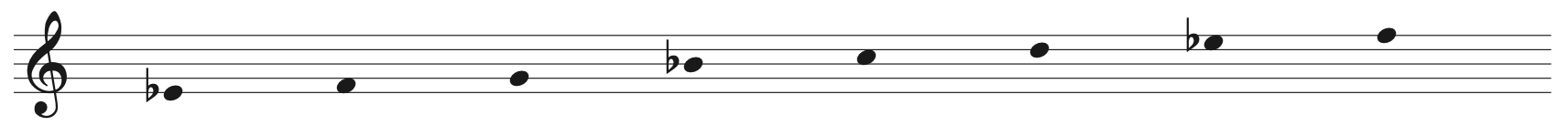

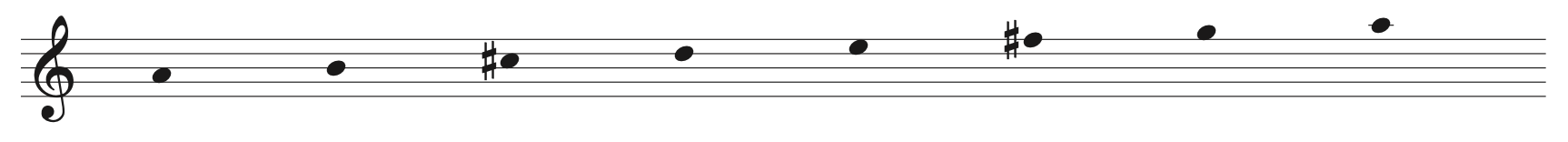

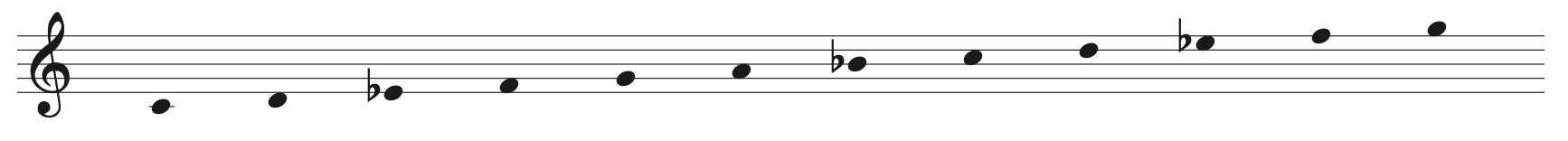

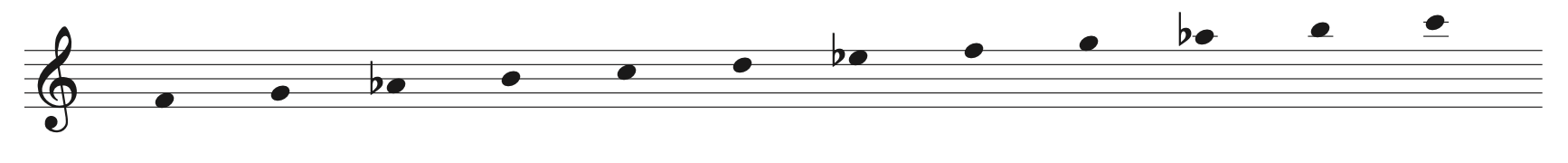

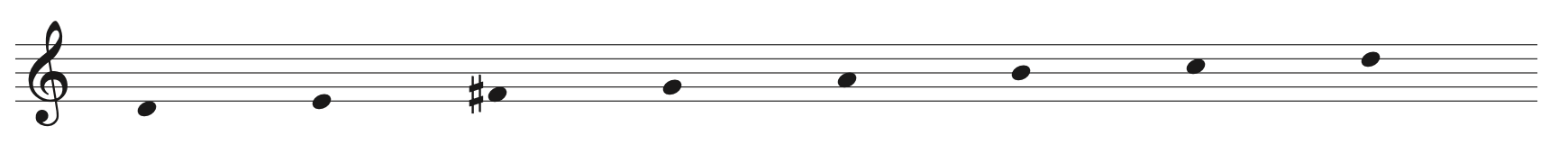

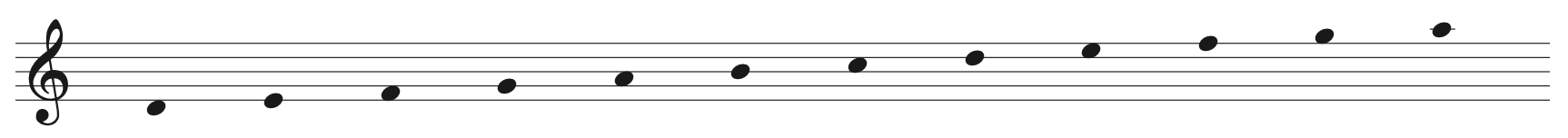

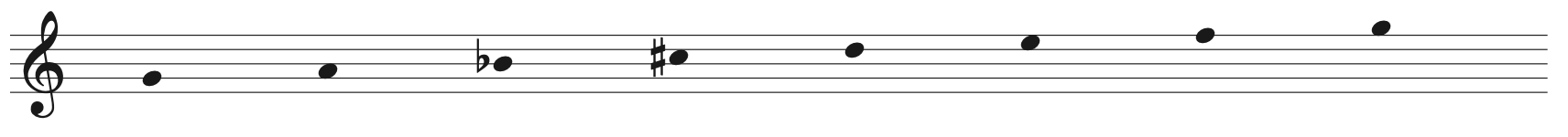

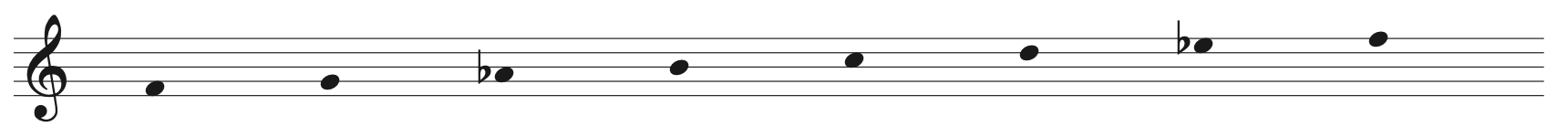

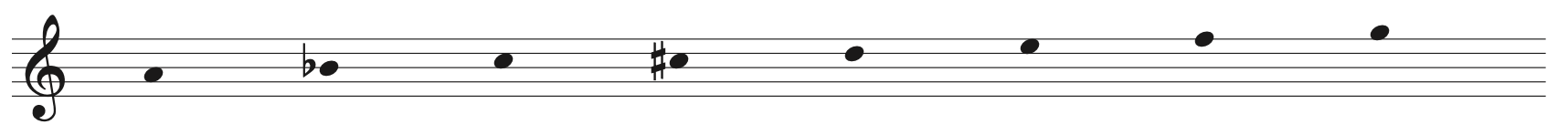

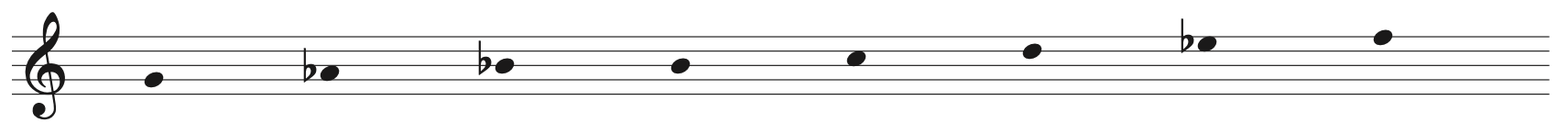

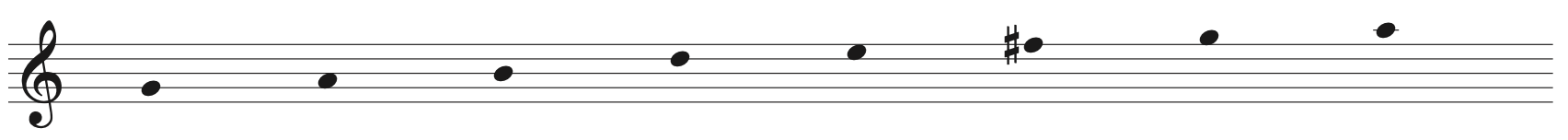

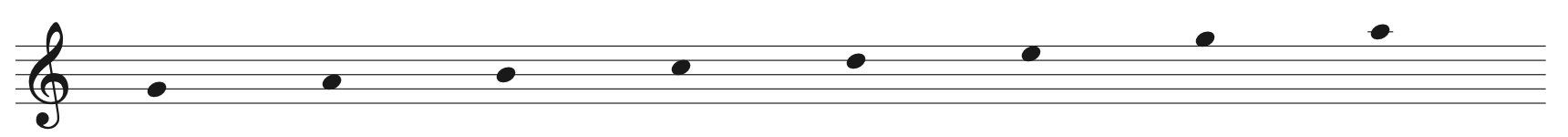

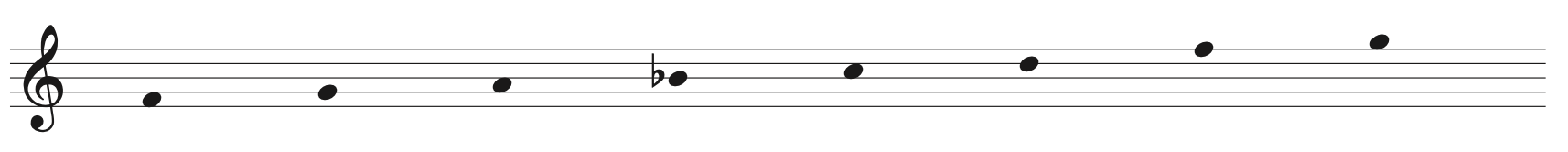

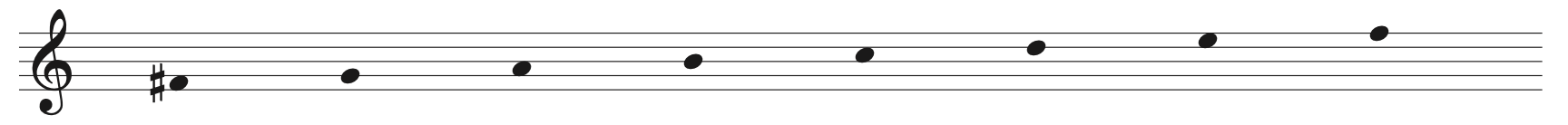

For handbell folks, the idea of “bass” seems to be from B3 downward (which corresponds well to piano music, where middle C actually is C4 – handbell scores are transposed down one octave from actual pitch). Bass ringers, then, are the members of the ensemble who typically handle the octave from C3-B3; if you’re fortunate to have more, those bass bells can extend all the way down to G1.

The challenge of bass ringing means that you have to keep up with the ensemble while slinging larger, heavier bells than everyone else. That entails more intense lifting and more forceful damping, because those large castings have to be tamed with more power than the little ones. The larger castings also mean that the clapper swing distance is correspondingly larger, so you have to account for that in the timing of your ringing stroke. They also take up a lot more real estate on the table; a treble ringer typically needs only about two or three feet of horizontal space to set up, while a bass ringer playing half of the octave C3-B3 needs about twice that. At the Bay View Week of Handbells, there are five “deep pit” ringers covering a double set of C2-B2 (plus one each of G1-B1 and C3), each with about eight linear feet of table space.

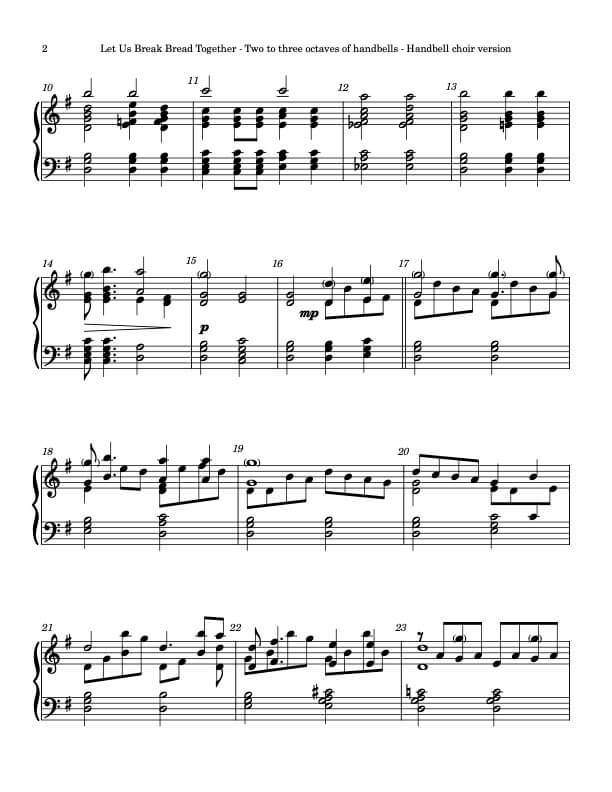

I think “specializing” is best interpreted as “being the one who gets to do it”; in many handbell choirs, the bass ringers are the ones who can actually wield those bells creditably. In the first handbell choir I joined, there were two of us playing the lowest octave for a year, and then my partner moved on. So I became a specialist by virtue of being given the opportunity to play “CD4, and anything to the left that you can manage”. That was the beginning; fortunately, I’ve had lots of great bass ringing teammates over the last few decades, so the journey hasn’t always been a solo endeavor.

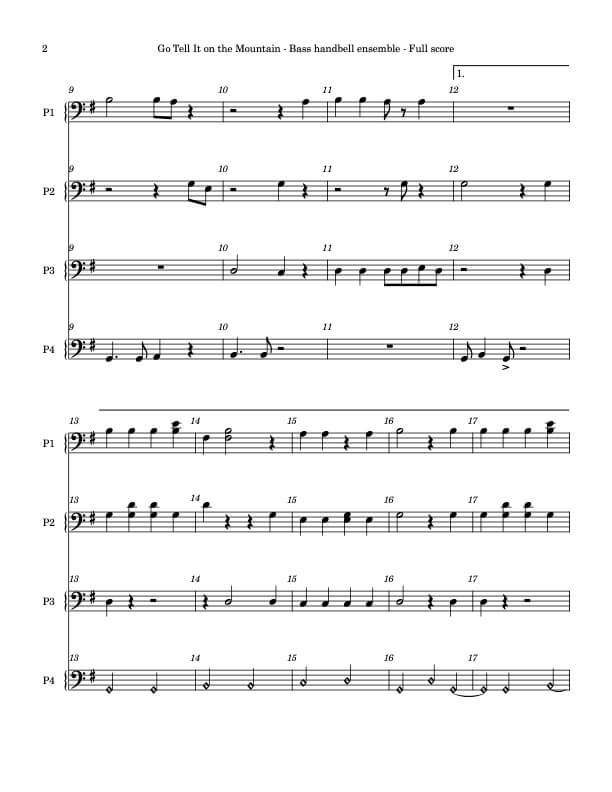

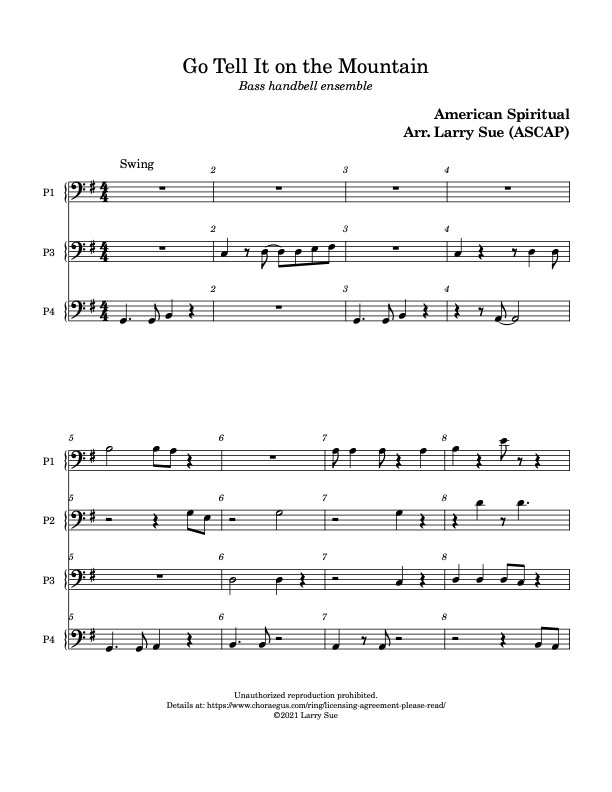

Eight years of the voyage was with Low Ding Zone, the World’s First Bass-Only Handbell Ensemble. We found that Bay Bells, the community ensemble with which we played, had five solid bass ringers. Someone had to ask the question (okay, it was me): “What if we formed a bass handbell ensemble?” For the eight years from 2005-2013, LDZ created and performed a lot of wild and crazy “heavy metal” music, and even now I spend some time writing a new piece for bass handbell ensemble, such as the “Dance of the Sugar Plum Sumo Fairy”.

By the way, there are even larger handbells out there. The Malmark factory has made some seriously huge bronze ones for research purposes, the largest of which is a G0 that weighs between 25 and 30 pounds. When it’s rung, the lip of the casting oscillates visibly (about an inch), and the mess of partials is so complex that it sounds like a gong. Carla and I saw this giant when we toured the factory in 2015, and couldn’t pass up the opportunity when asked, “you wanna ring it?”