The following is from a series of articles I wrote for Living Water, the choir I directed at Valley Church (Cupertino, CA) from 1987-2003, and at First Presbyterian Church (Mountain View, CA) from 2003-2011. While Living Water is no longer in action, the ideas I had the opportunity to present are just as valid now as then.

I’ve been wanting to write up some stuff about sight-singing for quite awhile now, and find myself with the time and motivation to do so (finally!). The first question to answer, of course, is: “Why?”

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 1

Well… sight reading is one of the most valuable assets a musician can develop. The essential reason is to reduce the amount of effort required to learn music: If a choir learns to sight read solidly, then their learning speed probably doubles (at least). It’s because the singers have progressed beyond the stage of having to do lots of part-pounding during rehearsals. Note: having to learn parts by hearing them – rather than reading them – is akin to learning by rote, which is at best a difficult and inefficient way to acquire new repertoire. I’ve likened this to trying to complete school as an illiterate by having someone else read all your textbooks to you aloud…

A second reason sight reading is oh-so-useful is that it gets you past the little black dots on the score and into the music itself. Put simply, the less time you need to spend on figuring out what the notes are, the more time you have available to make them into wonderful things for others to hear. Music isn’t paper and ink or mere notation – music is the auditory picture we paint when we do something with what’s on the physical page (well, yes, Steve and Phil – I suppose you could indeed have music on a virtual page…). To make the interpretation happen, then, we must be able to progress beyond the notes. Analogy: Actors don’t read scripts; they play roles – and so choirs must do more than thumping quarter notes.

There is another reason which, perhaps, is a little more subtle: Risk-taking. Sight reading involves the constant risk that the next note you sing will be a horrible clinker, that everyone in the choir will notice and point fingers at you, that you’ll be so-o-o-o-o-o embarrassed that you’ll turn brick red, melt down into your shoes, and be absorbed by their Velcro fastening straps… Just kidding, of course. My intention in giving us regular sight reading is to remind us that it’s okay to take risks – and that’s it’s okay to make honest mistakes in the process of learning to minister more effectively. Remember, we all mess up now and then (you’ve heard me sing the wrong verse of a hymn while songleading more than once, I’m sure), and the reminder of our fallibility actually ought to be welcome because it then can drive us to appreciate the Lord for His perfection and transcendence.

So, as Robert Conrad said with a battery on his shoulder in the Eveready commercial about fifteen years ago, “Go on. I dare ya.” Philosophical point: Ministry should be a place where people not only should enjoy succeeding, but a home where they should learn not to be afraid of risking failure for the sake of honoring God in a greater way. Give it all you’ve got!

Next time: We start on the technical stuff, probably with liberal doses of cheerleading.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 2

Musical literacy is a prerequisite to developing proficiency in sight reading. Well, duh – literacy is part and parcel of reading… All kidding aside though: being able to understand what’s on the page is the first step in being able to share it with someone else.

Over the past couple of decades, I’ve had the privilege of teaching the basics of reading music to a number of my singers. It really isn’t all that hard to get started in this; it’s usually taken about ten minutes to explain the fundamentals to those who couldn’t read music when we began. So it’s not a big scary sort of thing, and it certainly shouldn’t be a legitimate excuse for people to say that they can’t contribute to a choral ministry.

By the way, if you want to acquire this essential skill, Helen Cooper has written a wonderful little book entitled How To Read Music. It’s a great investment for the price, and I recommend it heartily.

One more thing about musical literacy: Music is a language, so you have to work at it to become fluent. Lest you think that this is an insurmountable obstacle, I hasten to remind you that there is a language in which 18% of the words are irregular, where alphabetic characters are used in inconsistent fashion, and where apparently similar sets of letters are pronounced differently in near-identical words. I also remark that you know this language; it’s English.

If you think about it, English has roots in many other languages. The great bulk of the words are taken from Latin and Greek, but there also are words from Arabic (“algebra”), French (“soiree”), Mesoamerican (“axolotl”), Polynesian (“luau”, “lei”, “lanai”), German (“dachshund”, “blitzkrieg”), Yiddish (“yarmulke”, “schmooze”), Chinese (“yin”, “yang”), and Japanese (“kamikaze”, “hara-kiri”).

Why aren’t “desert” and “dessert” accented in the same way? Why don’t “posses” and “possess” rhyme? Why don’t “sleigh” and “sleight” sound alike? Why are some letters phonemically schizophrenic (“a”), while others are seemingly redundant (“c”)? Why are there words such as “periodic,” “entrance,” and “tear” which have multiple pronunciations – and different meanings to match?

I don’t know, but I’m using these examples to show you that you’ve mastered a much more difficult language than the written expression of music. You can do this!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 3

I choose to break sight reading into the major components of “pitch reading,” “rhythm reading,” and “expression reading.” The first has to do with knowing what the pitches are on the music (without worrying about duration or feeling), the second addresses the relative time lengths of the notes, and the third deals with the interpretation of the score with respect to the pitch-rhythm mechanics therein indicated.

There are several ways to achieve an understanding of which pitches are to be sung in a particular song:

- Rote: This is the quickest way to learn your part; you and the other singers just sit around the piano and bang out your parts until you know them. It produces appreciable results very swiftly, and has been used for centuries.However, effective as it may be in the short term, learning music by rote ultimately is less efficient than sight reading; if a choir can sight read, then they shorten or even eliminate the time required to learn the notes on the page and can work on more music while also putting some serious time into learning the expressive aspects of the music.I’ve already alluded use of rote as analogous to having someone read all of your books to you all the way through school. Can it be done? Yes. Is it ultimately a reasonable and sane way to approach the subject at hand? No!

- Absolute Pitch: This is also known as “perfect pitch”; it’s the ability to identify pitches only by hearing – or to convert the written notes into the correct pitches. Until the last few years, it commonly was thought that perfect pitch was something you had – or didn’t. But more recently, a guy’s been around who says that he can teach anyone the art of absolute pitch – he must be able to do it, because otherwise he’d be hauled into court for violation of the “truth in advertising” principle.Assuming that it indeed is possible to teach anyone to have perfect pitch, it can be a very useful tool in sight reading. However, there are a couple of concerns which you need to address should you be blessed/cursed with this gift:

- How do you handle detuning? One difficulty some of these special people have is that they’re quite irritated when the group around them is in tune with each other, but is also blissfully ignorant of the fact that they’re ever so slightly off of A-440. I once tuned a piano belonging to a woman who had absolute pitch – and it was off a quarter step (half the pitch distance between adjacent keys). Now, that was a headache to her because of her gift.

- How do you handle transposition? What if the director wants to move the piece at hand into a different key – will the new set of diatonic pitches conflict with your perception of what’s on the page? I’ve heard that this is a really tough situation for some people with perfect pitch.

The bottom line is that perfect pitch is a great advantage in sight reading regardless of the difficulties which may occur.

- Relative Pitch: This is the “one step at a time” pitch reading method. It’s based on recognizing the “pitch distance” between consecutive notes, and therefore requires you to know how to sing each interval you might encounter. In practical terms, this means that you need to be able to sing about a dozen different intervals both going up and going down – a total of twenty-four intervals – but that you also need to be able to identify each of them correctly within a very small fraction of a second to keep up with the music.The training involved is in learning how to identify the intervals, followed by a period of application to solidify that education. A common way of doing this is to collect a bunch of songs which start with the needed intervals, for instance, a perfect fourth going up is the first two pitches of “Here comes the bride…” and a perfect fifth going up is the first pitch change in “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.”The advantage of learning this method is that it relies on familiar songs to flag the intervals sung. However, in practice I don’t find myself using it much because I don’t usually have time to figure out the interval, remember the flag song, and sing the interval before I’ve missed the note altogether. The mental processing speed required is somewhat beyond our normal operating mode.

Having now put you into a little more despair over the pluses and minuses of these three methods of pitch reading, I’ll come back to the subject next time…

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 4

I started learning choral parts by “pound and ‘peat” (rote). We spent a lot of time in sectionals in those days because then the amount of time used overall was half as great. However, I recall that the routine of go-to-the-piano-and-let’s-do-it-one-more-time got pretty old. In addition, I was starting to acquire a reasonable feel for sight singing even though I had no mental tangibles with which to explain how it worked.

Sometime during my seven years at my first church I also started singing parts from the hymnal and, when no written parts were available, improvising harmony parts. The truth of the matter is that I don’t want to give my mind an excuse to go to sleep on me, and so was exploring new vistas in my music. I still do this for the same reasons – and that continuing exploration into music ministry turned out to be one of the reasons I’m involved at Valley Church today: Paula Meil, our music secretary in 1987, heard me singing one evening service and asked if we were looking for a new home church. We said yes, she put me in touch with Tom, and the rest is history. God has been wonderful and great and gracious in all of this!

Note: Singing parts by improvisation is not sight singing. It, however, is a wonderful way to develop perception of the harmony surrounding you, and I recommend that you try it on a regular basis. Well – except with the choir: The composer/arranger usually has some special reason for writing the parts which are on the paper, so you should stick with what’s there unless there’s a good reason to change it (and if the director, including me, decides to change something, it’s not wrong to ask why he’s doing that).

Back to our regularly-scheduled programming After some weeks of “pound and ‘peat” I started to perceive the intervals in the music I was singing. This was a good thing because I don’t have perfect pitch. Having a background in piano helped quite a bit because after awhile my mind began to link the intervals in the music with how the tactile sensation of playing them on the keyboard – and connected them to the physical effort required to sing them. And once I’d learned to sight read, I found myself enjoying being part of a choir much more – well, except occasionally during our “pound and ‘peat” sessions…

And so, when I became a choir director, I sought a way to bring my singers to be able to sight read. I settled on the “relative pitch” method because I proceeded from the assumptions that rote wasn’t much fun and absolute pitch wasn’t musician-endemic (which, incidentally, was the prevailing doctrine at the time). We worked on this and achieved partial success. So it turned out that the relative pitch method had its deficiencies as well.

The most glaring deficiency of the relative pitch method is that if you miss even one interval, you’re lost big time. Analogy: if the Apollo missions to the moon were off even a fraction of a degree, our astronauts would still be sailing outward to the unexplored universe. They’d have starved to death by now, of course, but they’d still be heading away from home (does this sound like some summer camps?). In addition, relative pitch relies on having a complete understanding of all interval types, which means if you’re not there already, you might go off track the first time you encounter one of those little monsters.

I’d failed to account for the advantage of using the surrounding sound as a point of reference while singing. After all, the accompanist provides a clear pitch reference, and so it’s a good idea to take advantage of it (I had been for years, but didn’t think about it…). This led to the “anchors” method of sight singing.

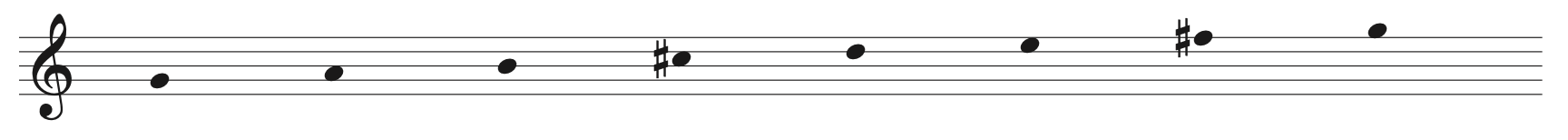

“Anchors” relies on knowing how to read music, and combines the positive aspects of positive pitch and relative pitch with perception of your surroundings. The essential concept is knowing where the (key) scale tones are (musical literacy / absolute pitch) and then using them as a basis for finding other pitches (relative pitch). The sound around you provides a continuing reference to the current tonality (key).

In general, intervals are navigated based on key scale tones, with an option to perceive small intervals via relative pitch. Accidentals are located by using a combination of the two, for instance, an identifiable scale pitch plus or minus a half step (more later about this…). Essentially, this method is less talent- and heredity-based and more education-based than the others, and therefore is accessible to more people.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 5

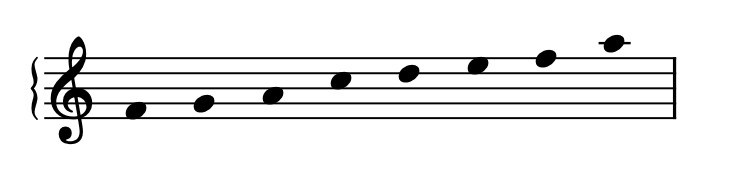

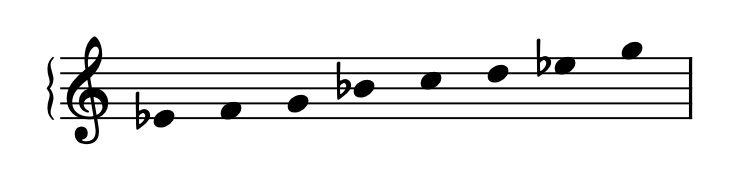

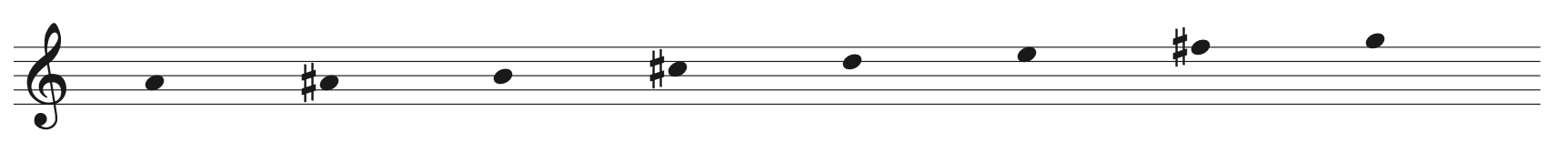

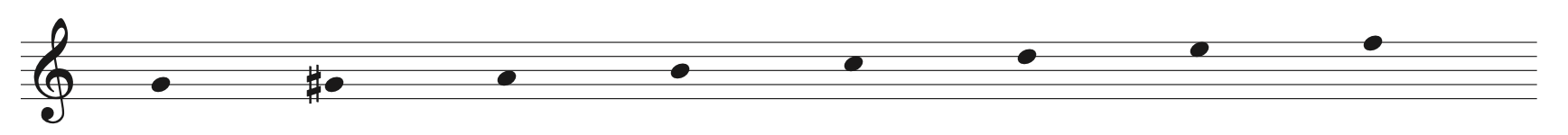

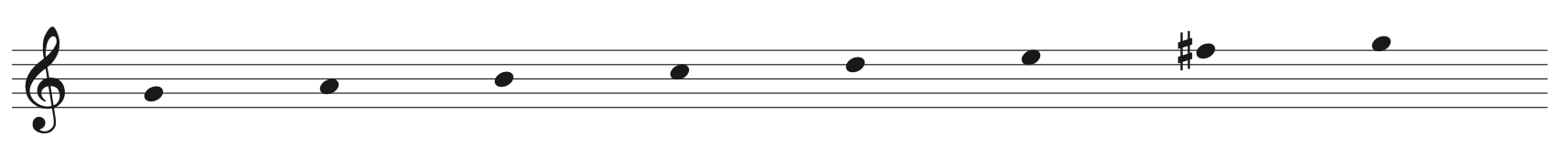

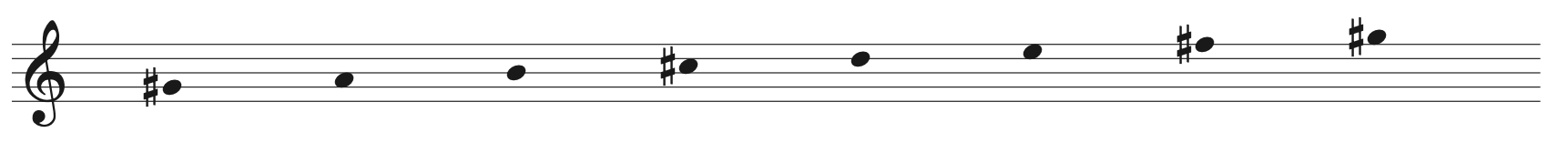

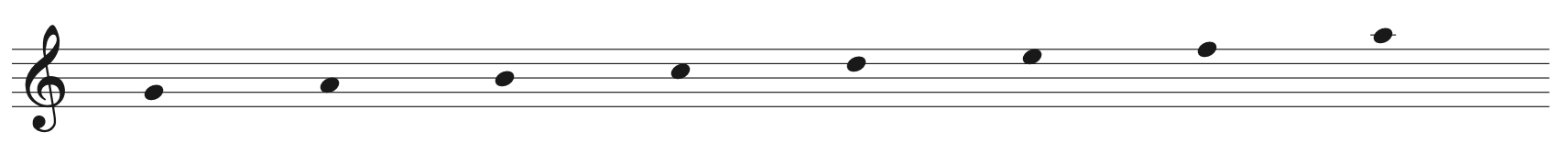

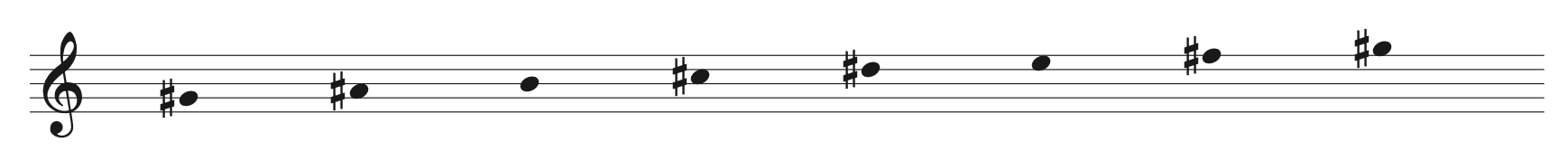

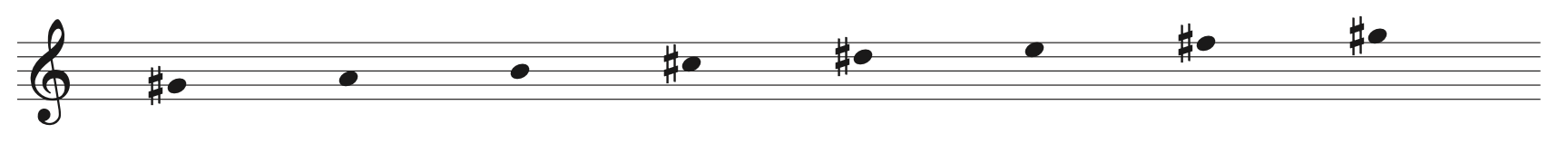

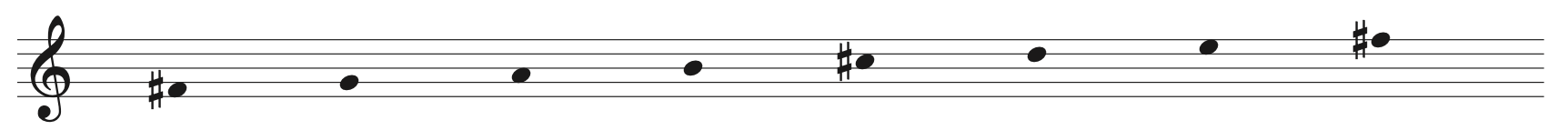

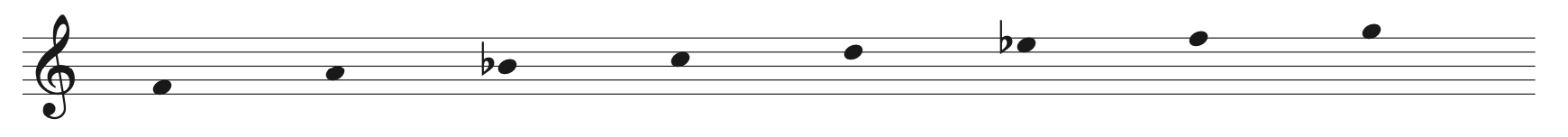

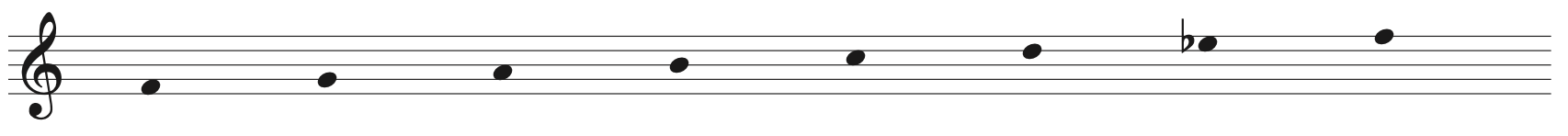

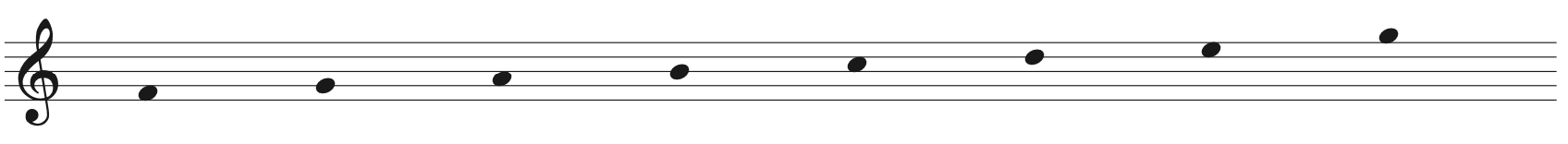

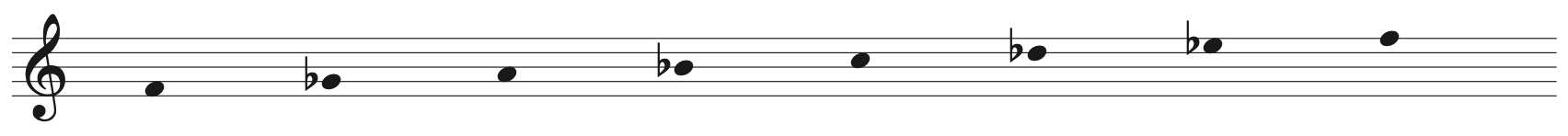

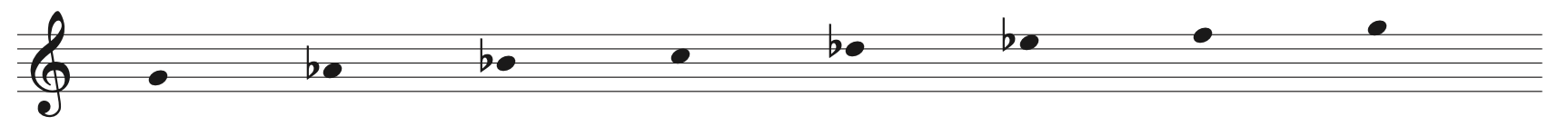

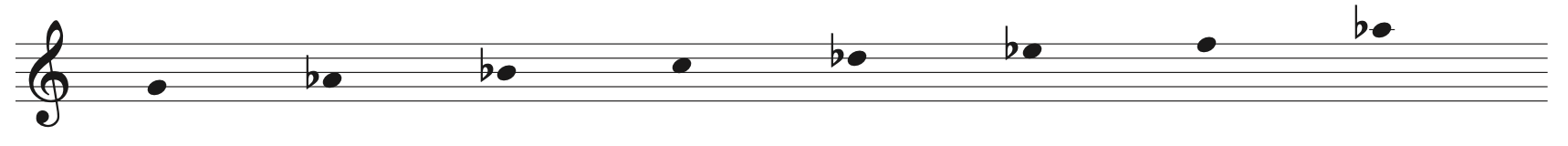

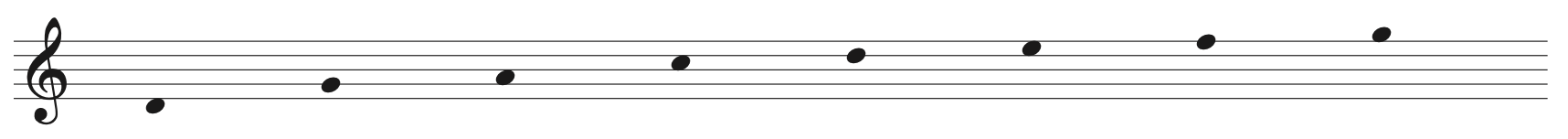

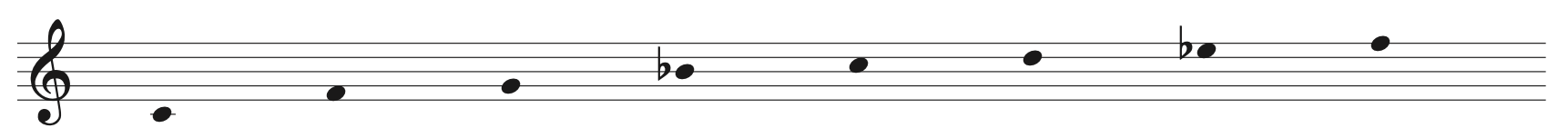

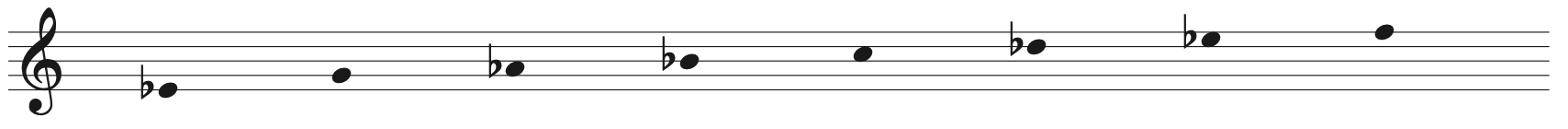

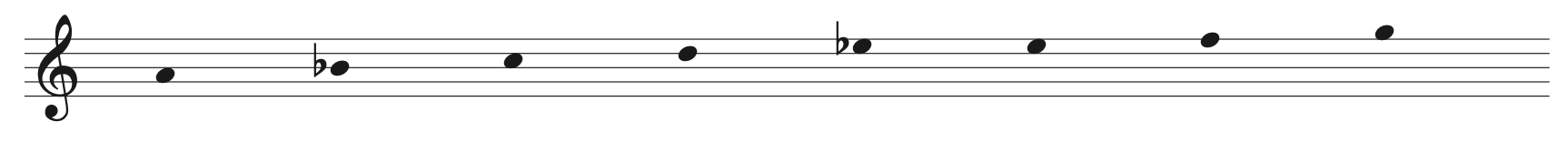

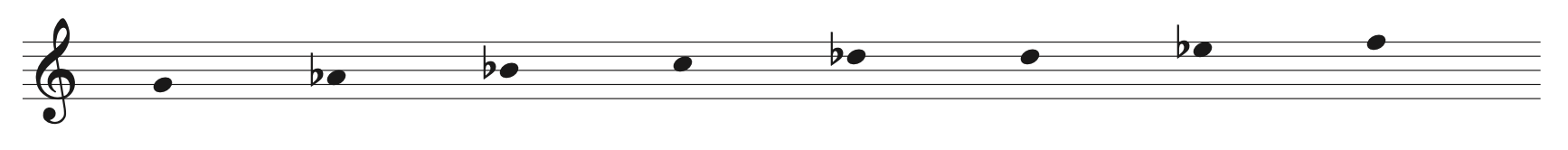

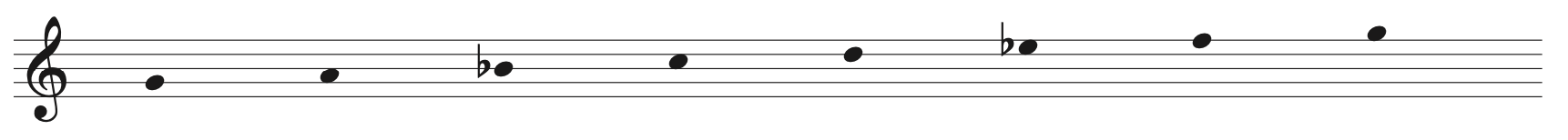

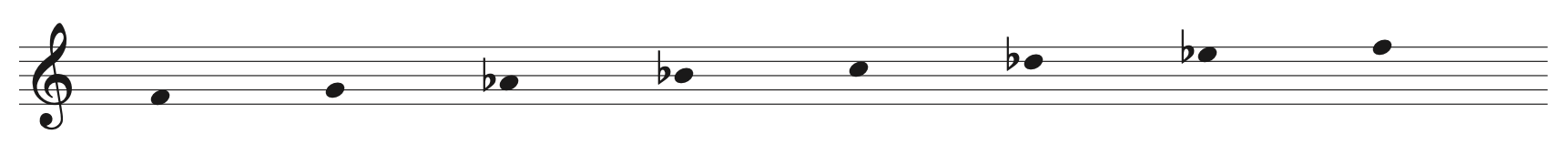

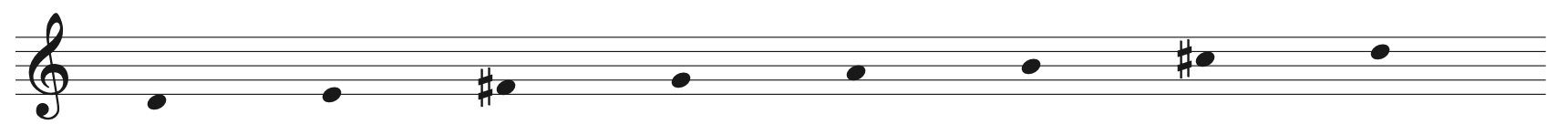

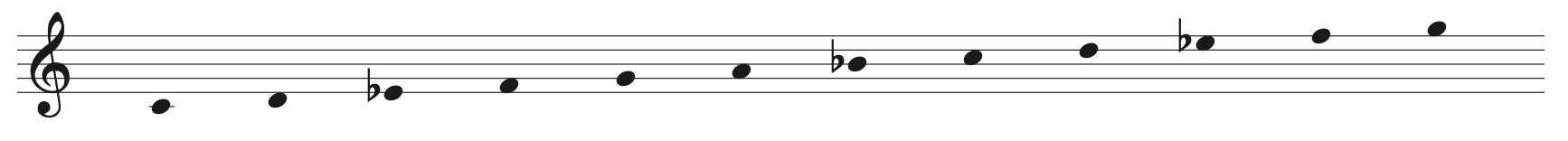

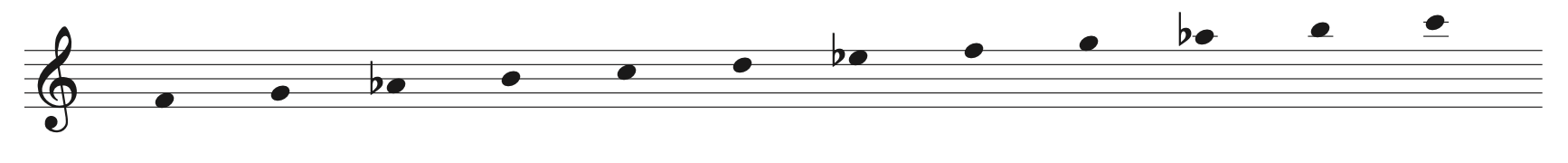

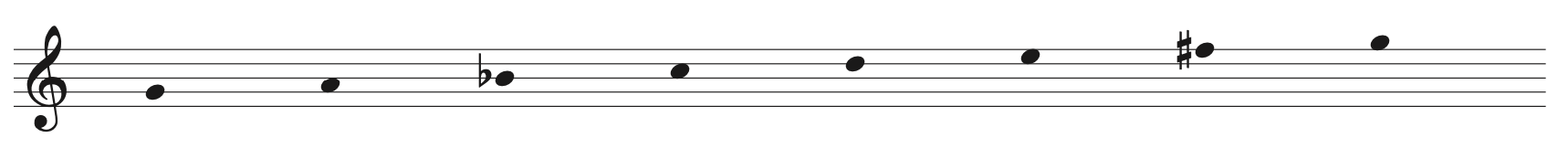

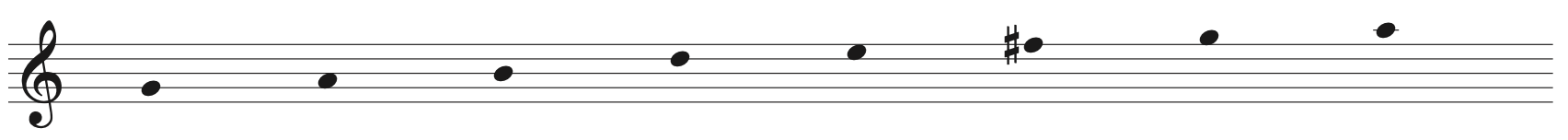

The “anchors” sight reading method is based on intervals which we find easy to sing. In the American mindset, this generally is based on the [European] major and minor scales. For instance, the melody “Joy To The World” begins with a descending major scale.

The base intervals for “anchors” are also determined from what is known as “tertian harmony,” that is, harmonic structures which are derived from using alternating scale tones (now that’s a mouthful). Restated so as to be less theoretical: Most of our Western harmony is based on the concept of the triad, for instance, the chord formed by C-E-G – the first, third, and fifth tones of the C major scale.

We hear triads quite naturally because they are the harmonic essence of our music. We also hear major scales and, to a lesser degree, minor scales easily for the same reason. And it turns out that, as a result of this “immersion education” which you’ve received since we were very young, you already have most of the “anchors” system embedded in your mind!

The “anchor tones”: The basis of the “anchors” system is knowing where a few key scale tones are. As a reference, here’s a table of the scale tones with their formal names; I’m providing it because these terms will arise both as we continue our exploration and as we sing. “Degree” is the number attached to the formal name. Example pitches are provided for the C major (CM) and C natural minor (Cm) scales.

Degree Formal Name CM Cm

------ ------------ ------ -----

1 Tonic C C

2 Supertonic D D

3 Mediant E E-flat

4 Subdominant F F

5 Dominant G G

6 Submediant A A-flat

7 Leading Tone B B-flat

8 Octave/Tonic C C

You’ll notice that degrees 1 and 8 are both have the same formal name. This is because the scale extends infinitely in both directions (though we can’t hear most of it) and so this periodic sequence starts over every seven notes. One man’s octave is another man’s tonic…

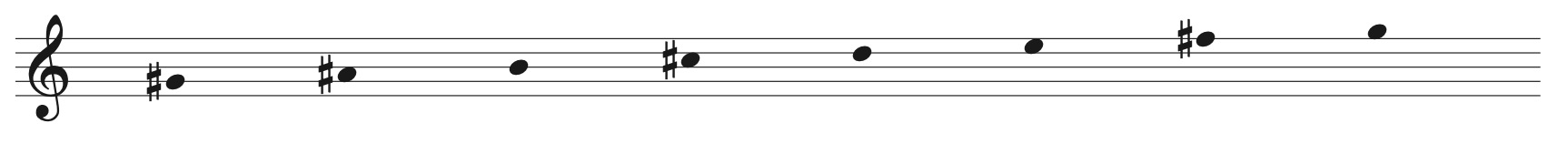

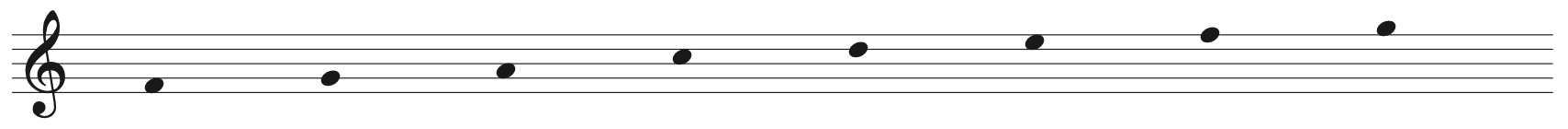

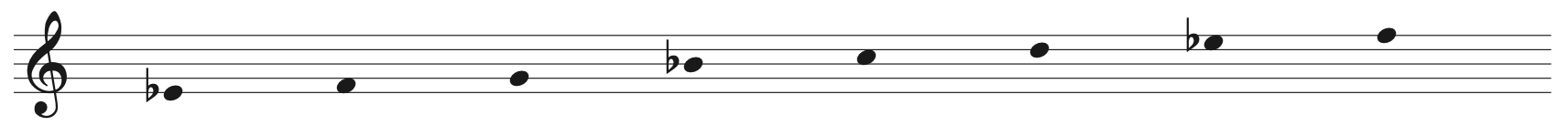

The tonic/octave: The first/last tone of the scale is the most important anchor. It’s easy to find because it’s the note on which we want to end the melody. Funny thing, that’s exactly what happens in almost every melody you’ll meet; notable exceptions are “The First Noel,” “Lord, We Love You,” and “I Wonder As I Wander.” Another convenient way to find the tonic is to hear the key given, and then to sing “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” or “Frere Jacques” – the first note of each melody is the tonic. It also is important to identify the actual keyboard name of the tonic from the key signature. This is pretty easy:

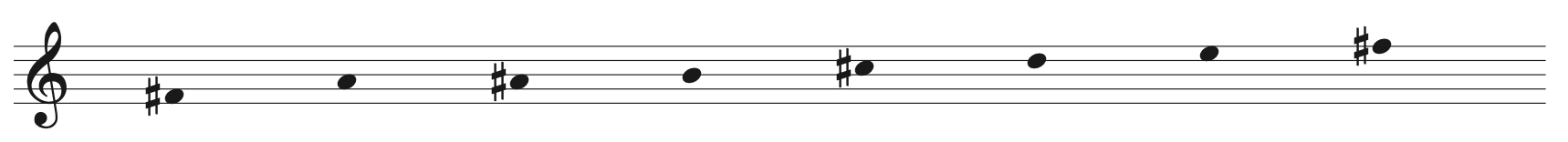

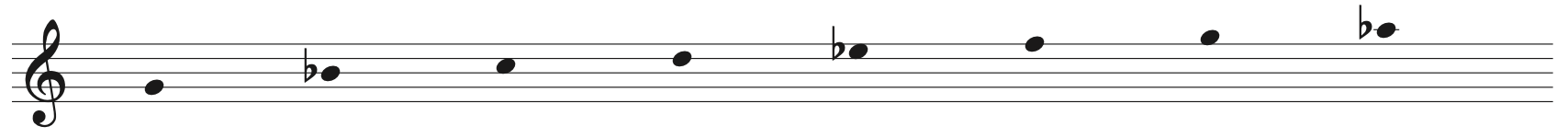

For major keys:

- If there are no flats or sharps in the key signature, the tonic is C.

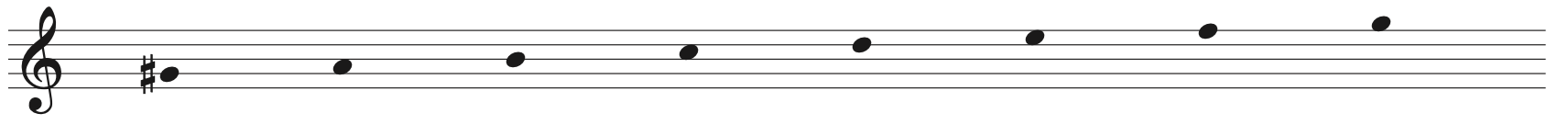

- If the key signature contains sharps, the tonic is the next key upward from the rightmost sharp in the key signature.

- If the key signature is one flat (i.e. B-flat), the tonic is F.

- If the key signature contains more than one flat, the tonic is the note indicated by the second-to-last flat.

Here is a table of key signatures:

Stuff in key Major Key Minor Key

Signature

------------ --------- ---------

7 flats C-flat A-flat

6 flats G-flat E-flat

5 flats D-flat B-flat

4 flats A-flat F

3 flats E-flat C

2 flats B-flat G

1 flat F D

0 C A

1 sharp G E

2 sharps D B

3 sharps A F-sharp

4 sharps E C-sharp

5 sharps B G-sharp

6 sharps F-sharp D-sharp

7 sharps C-sharp A-sharp

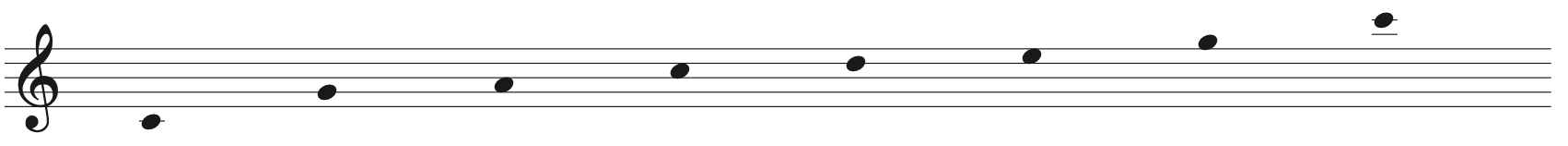

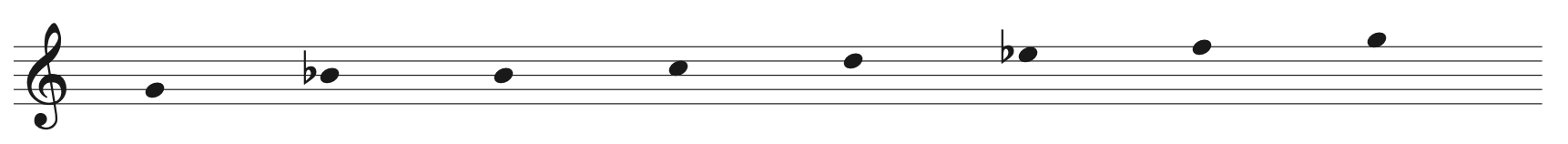

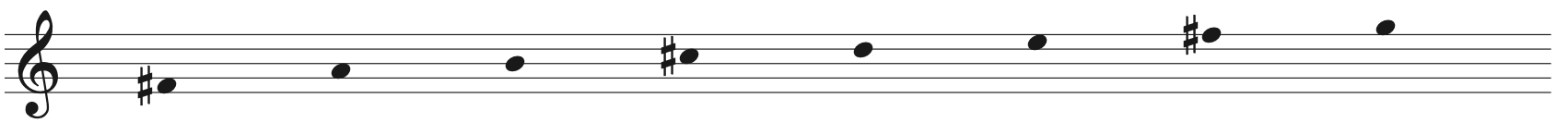

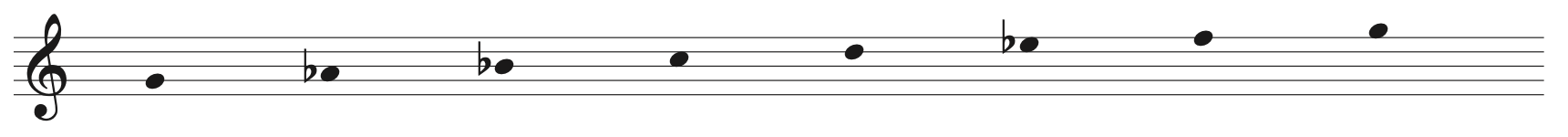

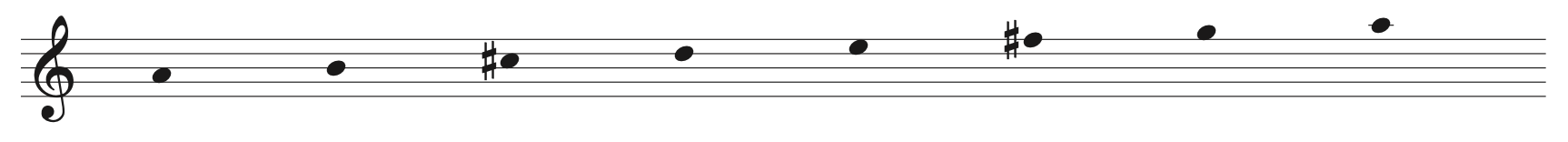

The dominant: The fifth tone of the scale is the second most important anchor because it’s the base note for the “dominant seventh” chord, which is the penultimate chord in almost every piece of music we hear. Basses, you have it pretty easy here because many of your parts end with the tone sequence “dominant-tonic.” There are a couple of easy ways to acquire a feel for the dominant. The first way is to sing “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” – the dominant is the tone of the second “Twinkle.” The second way (my favorite) is to sing the marching song of the Wicked Witch’s soldiers from “The Wizard of Oz”: “Oh-Ee-Oh, Ee-Ohhhhhhh-Oh…”

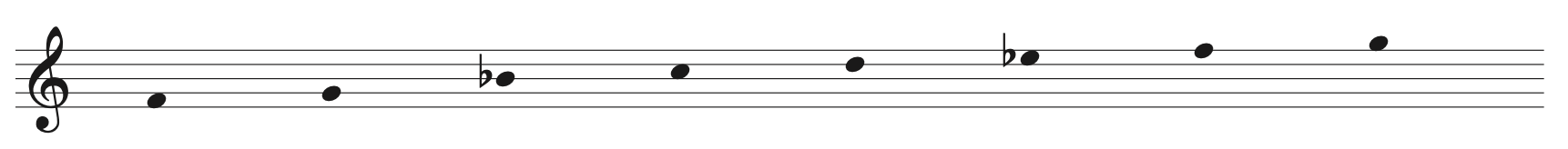

The mediant: The third foundational anchor is the third tone of the scale. It has two important uses as an anchor. The first is to subdivide the frequency span between the tonic and the dominant roughly into halves. This means that if you’re dealing with notes in that range, you’ll have an easier time finding an anchor with is close (or the same as) the note you’re singing.

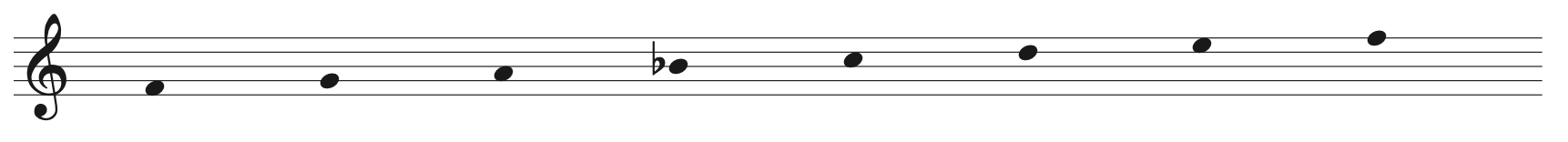

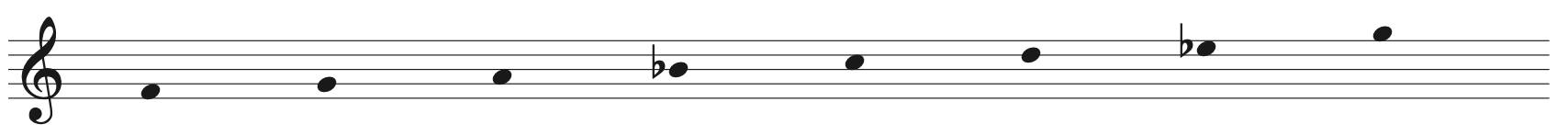

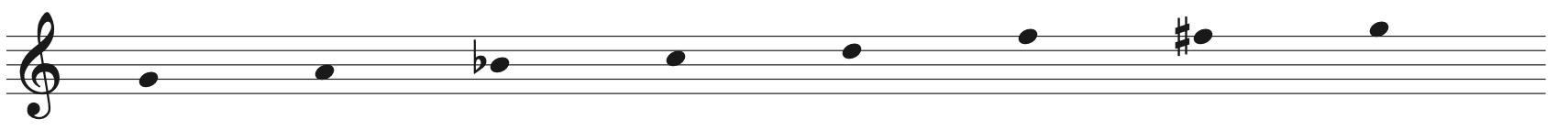

The mediant’s other important use is to aid in establishing whether the current tonality is a minor or a major key. If you check out the key signatures mentioned a couple of subsections ago, you’ll find that the third scale tone of C major is E-natural, while the third scale tone of C minor is E-flat. Having this pitch in mind not only serves both to determine the type of key being sung; it also helps to define all of the tones in the entire scale.

Theoretically, the mediant defines tonality; in practice it represents the (diatonic) third, which is the easiest harmonization to sing. Proof of this: Have you noticed how people split to parts on the last word of “Happy Birthday To You”? The next time this happens, observe what notes are being sung as harmony parts. You’ll find, at the end, that the majority of people who eschew the tonic are singing the mediant.

This is part and parcel of the “tertian harmony” from which the harmonic structure of most of our music is derived. “Tertian” refers to the use of thirds, and analysis of the majority of instrumental and vocal works reveals that the third is the base interval used in building harmony.

The leading tone: The leading tone is the scale tone just below the octave. It’s so named because of its innate instability within its key – it drives the performer and the listener toward the tonic/octave. Example: Hum “shave and a haircut, six bits” to yourself. Now hum just “shave and a haircut, six” – you’ll find that that leading tone on “six” makes you want to move right on to the last syllable, which falls on the tonic.

Part of the reason that the leading tone is so strong in terms of the purpose defined by its name is that it’s a third above the dominant (therefore harmonizing with it). By virtue of this, it defines a harmonic structure which readily resolves to the major chord based on the tonic (note, however, that this observation is based on the assumption of Western [European] harmony, so depending on your background you may or may not be impressed by this statement).

Bottom line: The result of having the first, third, fifth, and seventh scale degrees (tonic, mediant, dominant, and leading tone) as anchors is that no pitch is farther than a whole step away from an anchor. This makes life pretty easy, as it’s not too hard to learn to find a pitch a half step or a whole step away from one you already know.

Next time: We fill in the holes between anchors.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 6

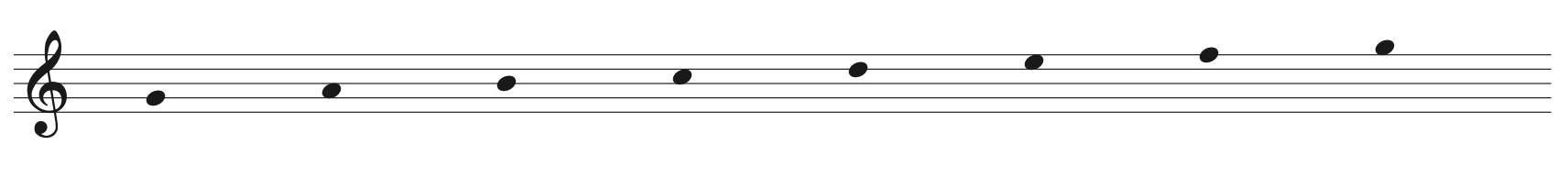

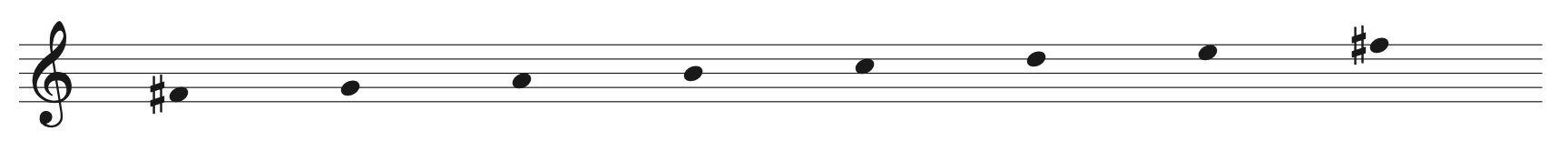

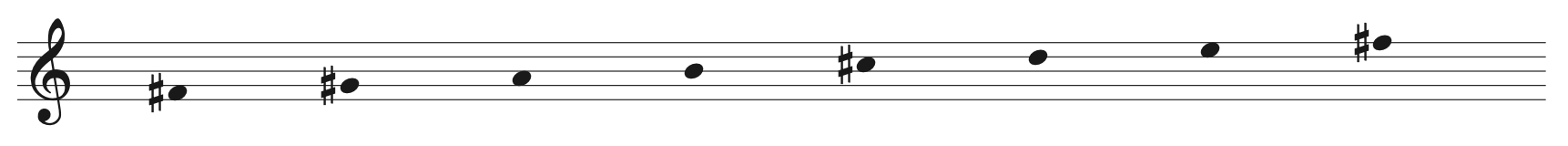

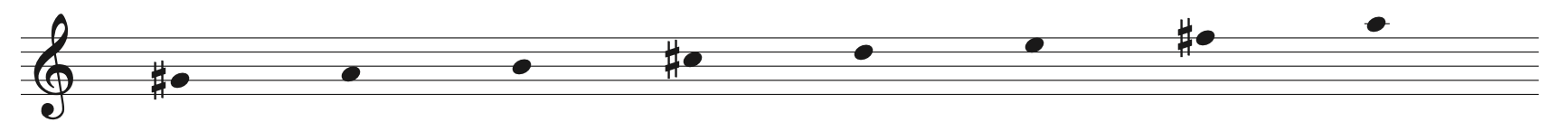

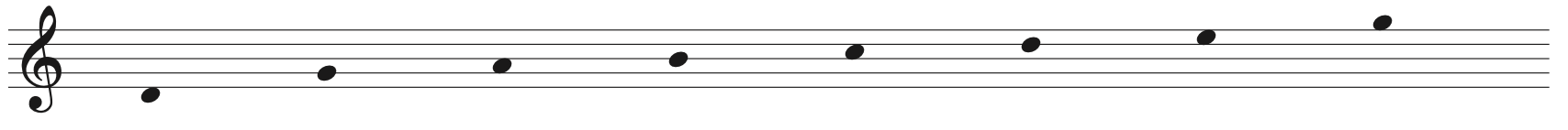

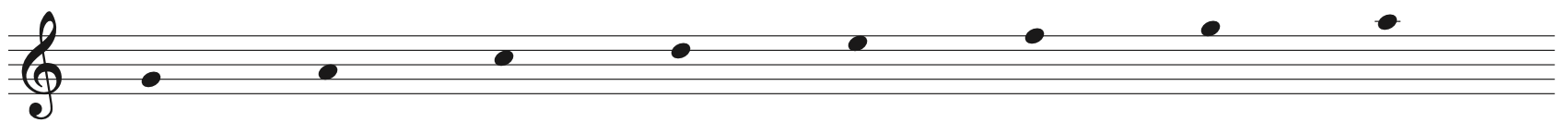

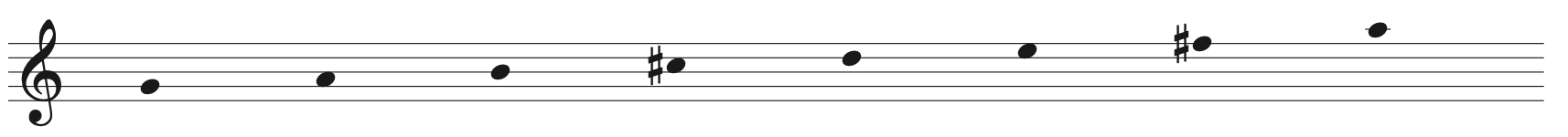

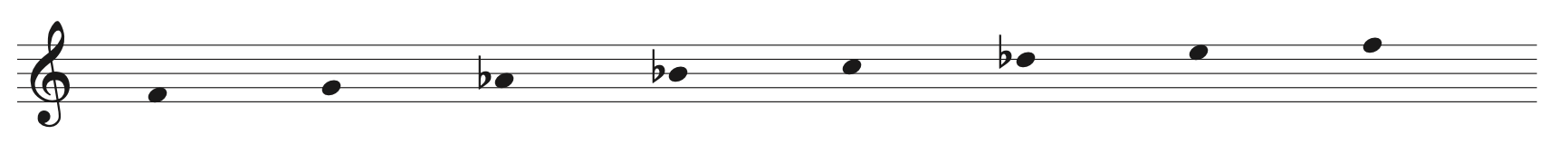

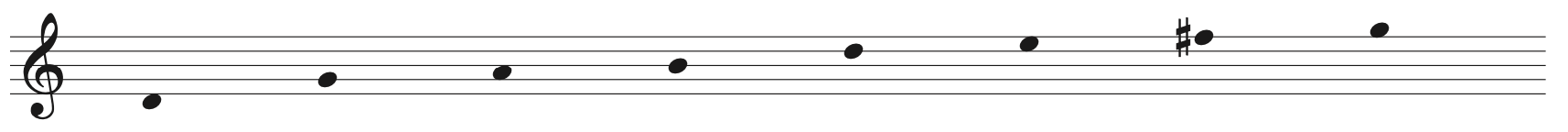

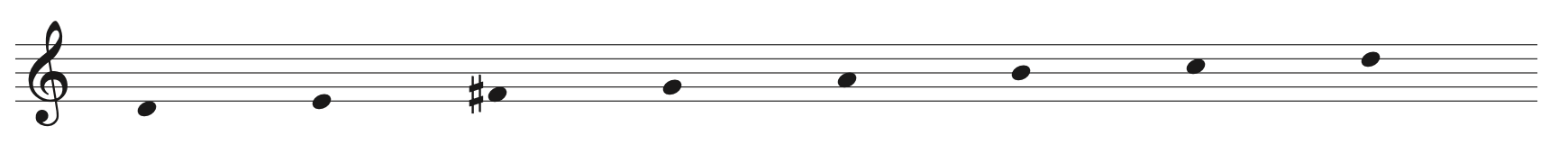

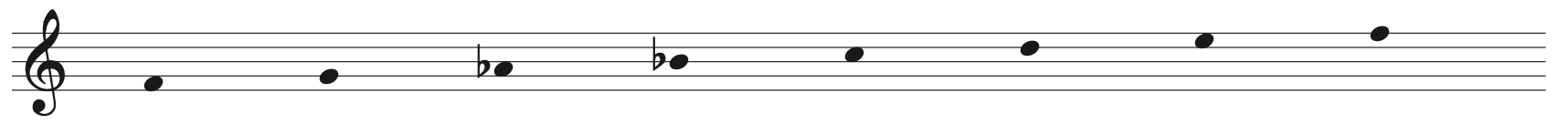

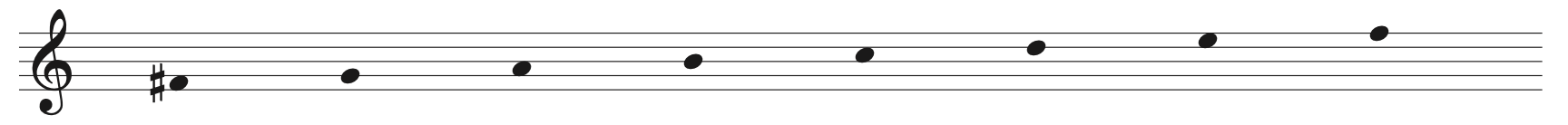

Now that you’ve learned the odd scale degrees (1 = tonic, 3 = mediant, 5 = dominant, 7 = leading tone) as the basic anchors, we can fill in the holes between them. These are the three remaining scale degrees:

- 2 = supertonic

- 4 = subdominant

- 6 = submediant

To find them when singing, simply sing the scale tones in between 1 and 3, 3 and 5, or 5 and 7. Note, however, that I’ve assumed that you know where the tonic is, and then also have a pretty good idea of which pitch you’re supposed to be singing based on the musical score.

Supplementing all this with relative pitch: This is where relative pitch can be useful. Sometimes you’ll have a really good idea of which scale tone you’re singing, and sometimes the score will be sufficiently accidental-prone so that performing the computation of “just which scale degree that is” becomes impossible in real time. However, if you have some understanding of relative pitch, you can make life somewhat easier by knowing which interval you’re to sing.

For a pure “anchors” approach, the thought sequence would be “What’s the key signature? What’s the letter name of the note? Which scale degree is it? Which anchor do I use? Sing it!” while the relative pitch approach is “What pitch did I just sing? What’s the interval to the next pitch? Sing it!” Note, however, that relative pitch actually is a slightly camouflaged version of “anchors” because WHEN YOU SING EACH INTERVAL YOU’RE USING THE PREVIOUS NOTE AS A TEMPORARY ANCHOR.

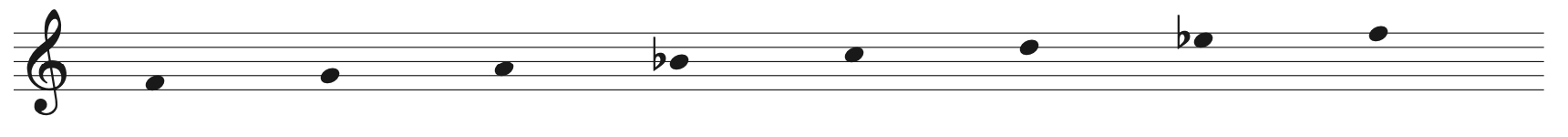

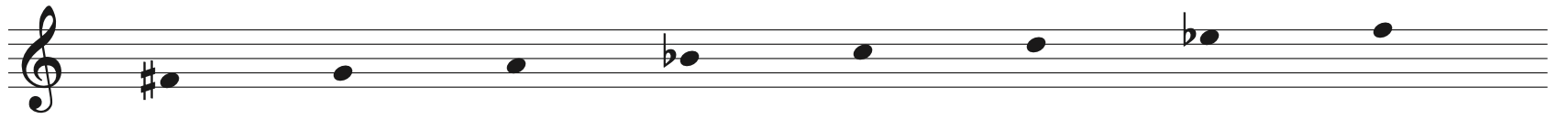

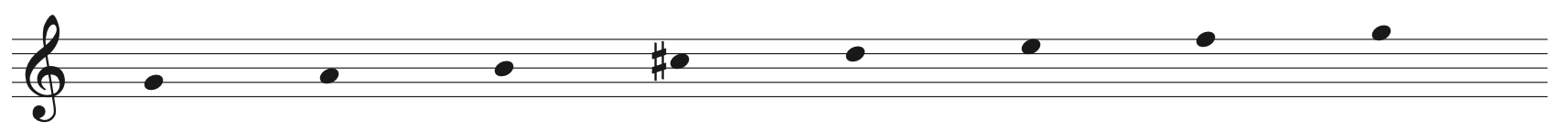

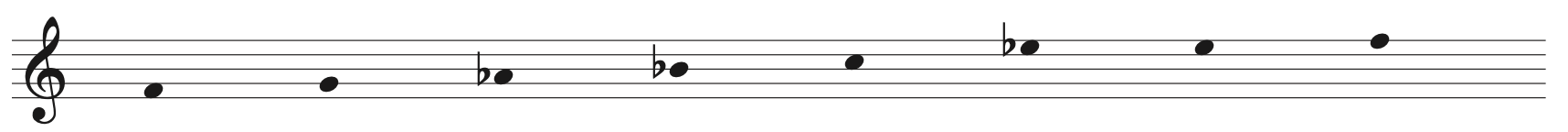

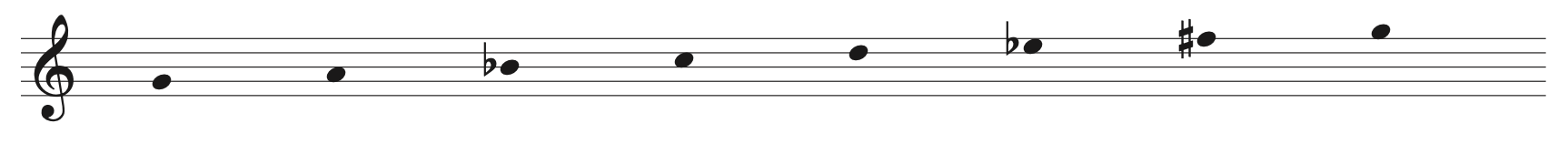

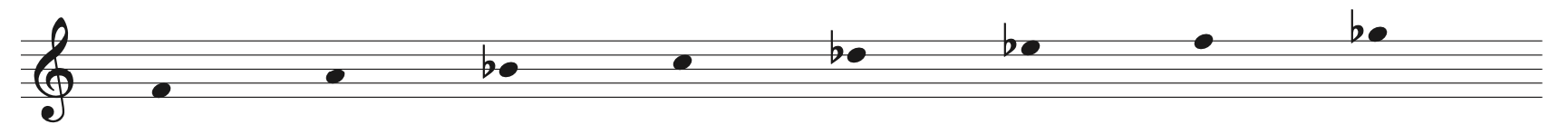

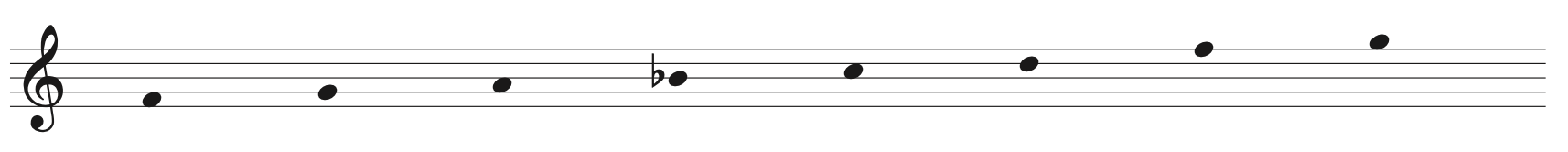

Accidentals: These are the nondiatonic pitches on the score, indicated by sharp, flat, and natural symbols which don’t correspond to the notes indicated by the key signature (the ones which actually are notes in the current key are known as “courtesy accidentals”). But even though there are five nondiatonic pitches in each scale (within enharmonicity), it doesn’t mean that we need to learn more anchors.

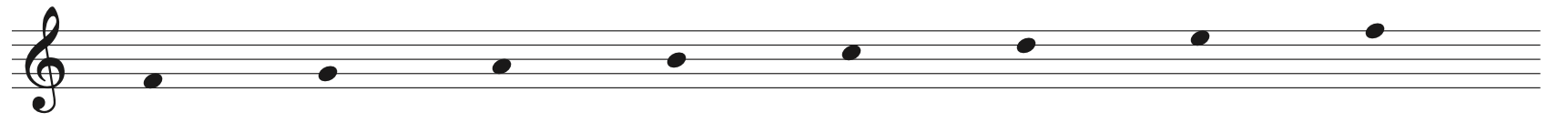

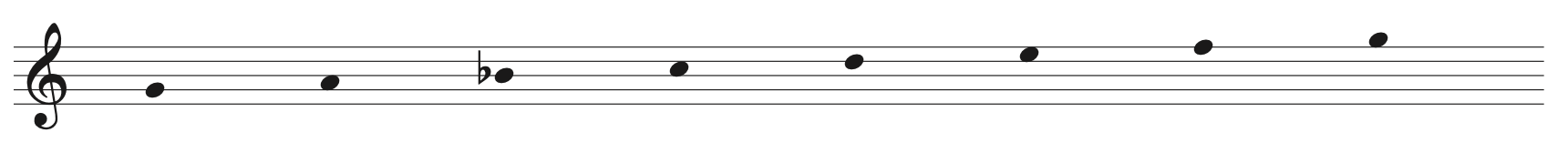

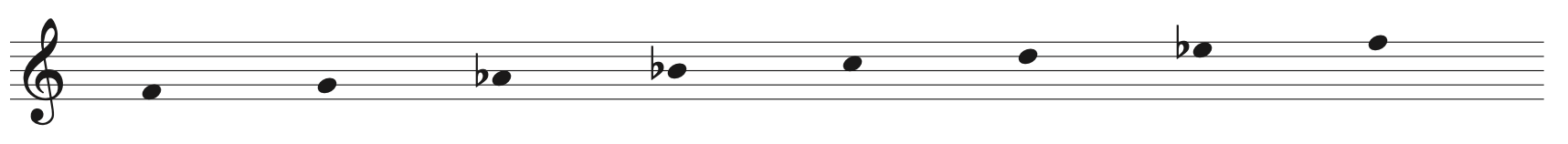

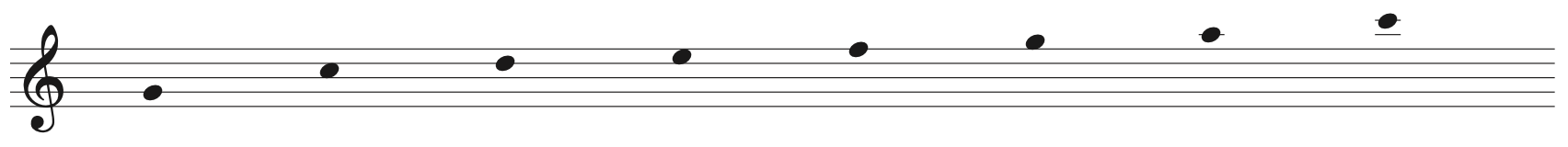

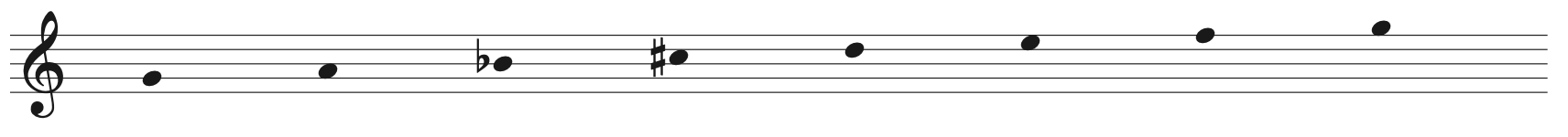

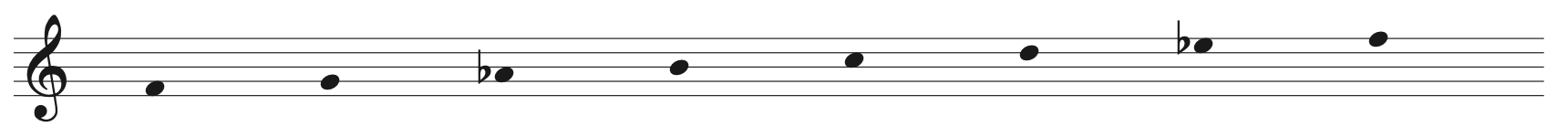

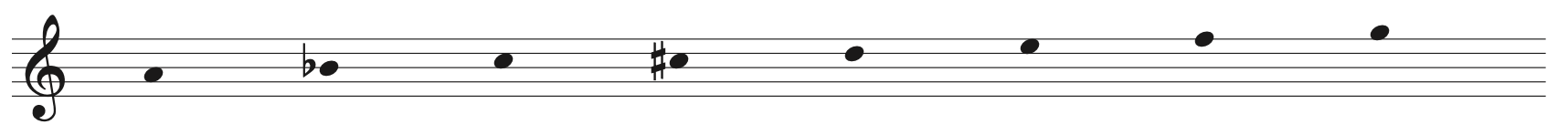

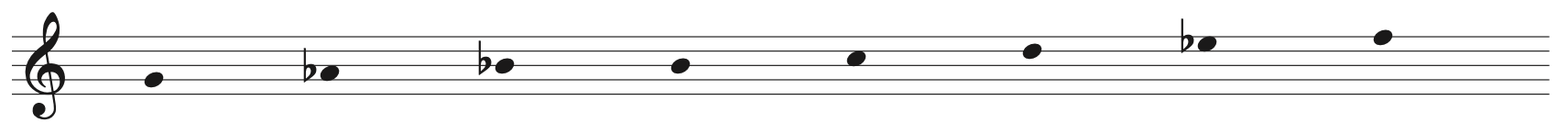

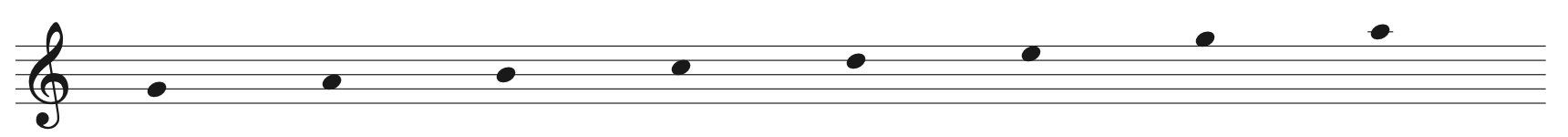

It only is necessary to learn to sing “half steps” and “whole steps.” These are the two smallest possible intervals based on our twelve-tone scale, and all that is required to sing them is a perception of the “pitch distance” between adjacent scale tones. The major scale is composed entirely of these little intervals:

- 1-2 whole step

- 2-3 whole step

- 3-4 half step

- 4-5 whole step

- 5-6 whole step

- 6-7 whole step

- 7-8 half step

If you sing your way up the major scale, you’ll find that the intervals 3-4 and 7-8 are smaller (i.e. have a smaller frequency width). These are the “half steps” in the major key. All of the other intervals are “whole steps. ”

It turns out that the nondiatonic pitches are no more than a half step from any of the 1-3-5-7 anchors, so once you know how to sing half steps and whole steps in addition to being able to find anchors the nondiatonic pitches should be relatively (pun intended) easy.

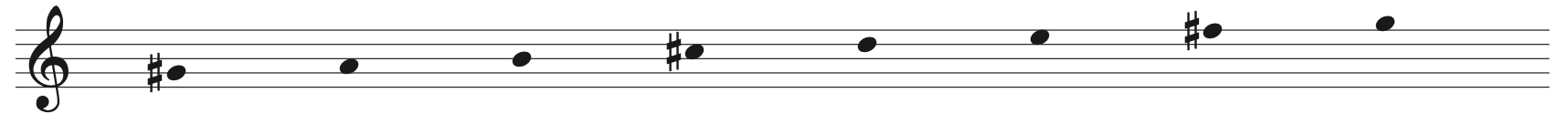

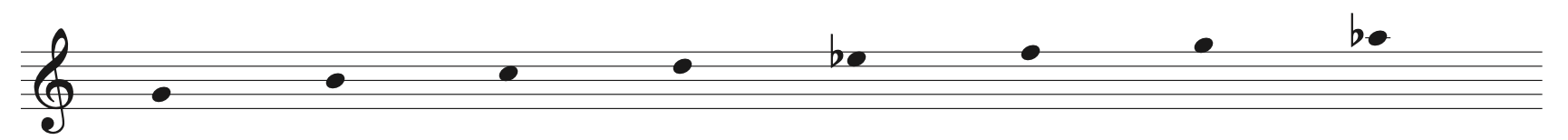

There actually are two ways to find pitches within the “anchors” approach:

- For small intervals: Find notes by starting from where you currently are and jumping, say, no more than a couple of whole steps up or down. This is a relative-pitch-based method, and it probably is the faster than finding anchors once you can identify intervals with sufficient speed.

- For large intervals: The wider the interval, the greater is the need for an understanding of where to go; this is where the anchors come in. So if the upcoming jump is a big one, find the corresponding anchor and work with it.

For medium-size intervals, you can use either method easily (note, however, that the dividing line between which method you use is a choice based on your God-given skills).

Accidentals: Accidentals have been a musician’s thorn for centuries because they don’t fit into the diatonic scheme and therefore require a more effort. However, a combination of the two methods above can make them much easier: Simply find the anchor which is closest and treat the accidental as a small interval from that anchor.

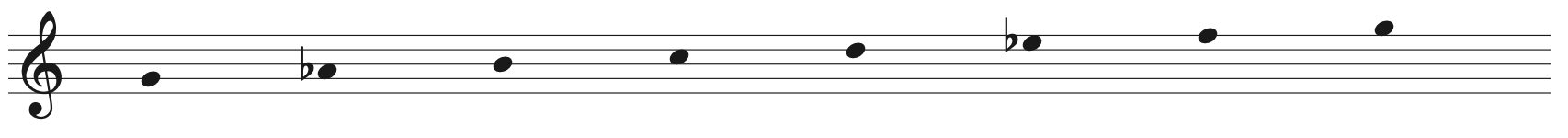

Alternate keys: One more item for now… You can use “alternate key signatures” to sing intervals. That is, it might be easier to sing a sequence of notes in a key other than the one indicated by the written key signature. It takes awhile to develop the perception of just which key is appropriate, but the best clues are found in the accidentals in the score (they’re put there either for chromaticism – which involves singing half-steps) or modulation – which indicates movement toward a new key).

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 7

We’re done (for the moment) with our exploration of pitch reading, and so will be moving on to the next aspect of sight reading as a whole. If you haven’t noticed, I like to break large topics into what I perceive to be manageable subsections, and then treat each minor topic separately before integrating them into a (hopefully!) coherent whole.

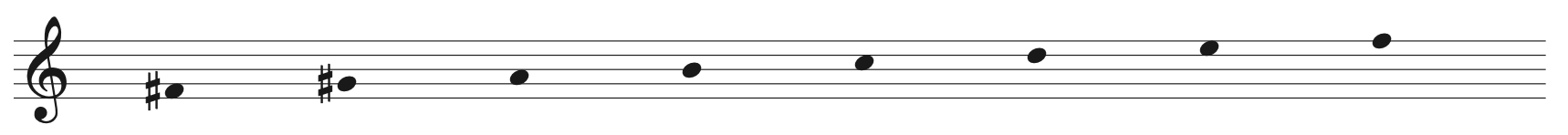

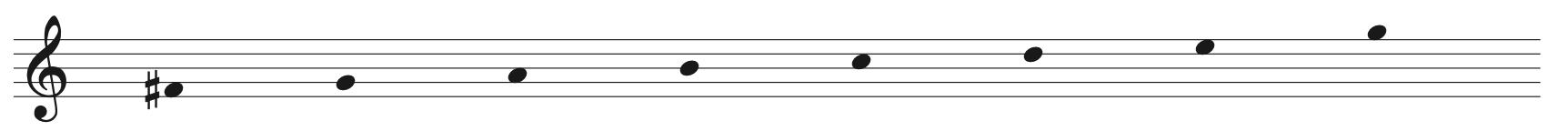

The second subject we’ll tackle is “rhythm reading,” that is, the on-the-fly determination and execution of the relative durations of the notes on the score (say that three times fast…). The prime concept is that of the “time signature.” As we have a key signature to tell us which pitches are endemic-diatonic to our tonality, we have a time signature which specifies the temporal (i.e. time-based) structure of the music.

Back to basics: I know you all read music to some degree, but as the definition of the time signature is the essence of the next few segments it’s reasonable to do a little bit of recall. As you know, the time signature is composed of two numbers which are stacked on each other at the left end of the first measure. The upper number tells how many time units there are in each measure; the lower number indicates what sort of note represents one unit. For instance, “three-four” means that there are three units (beats) per measure, and that a quarter (i.e. one-fourth) note is the unit note. If you like, you can treat the time signature as a fraction which tells you how many whole notes each measure contains.

As you’ve seen occasionally, however, the time signature changes in the middle of more than a few songs, but even if the time signature is different its purpose is still the same. Usually when this happens the composer/arranger is trying to say something a special way, perhaps a little like the way Batman and Robin (in the OLD Adam West series) used to talk in more or less complete, intelligible sentences, interspersed with POW! and WHAP! starbursts when they were administering pain to the bad guys.

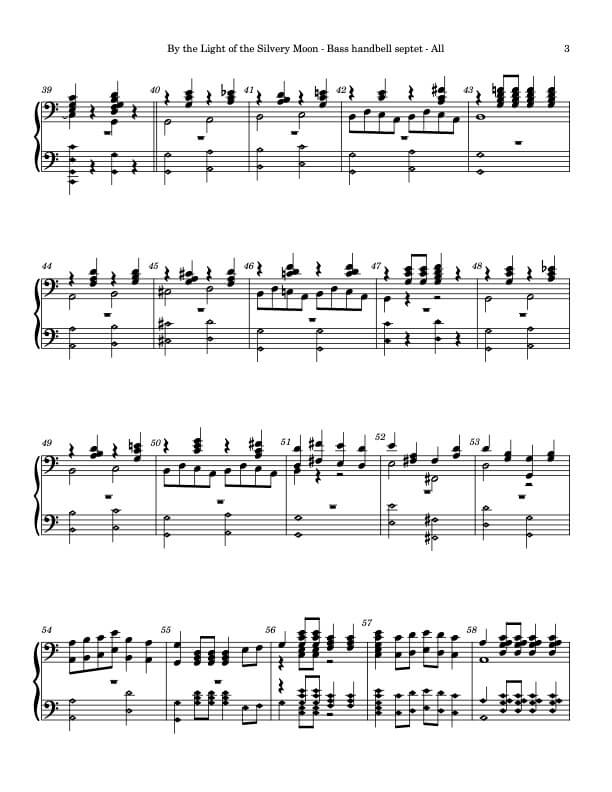

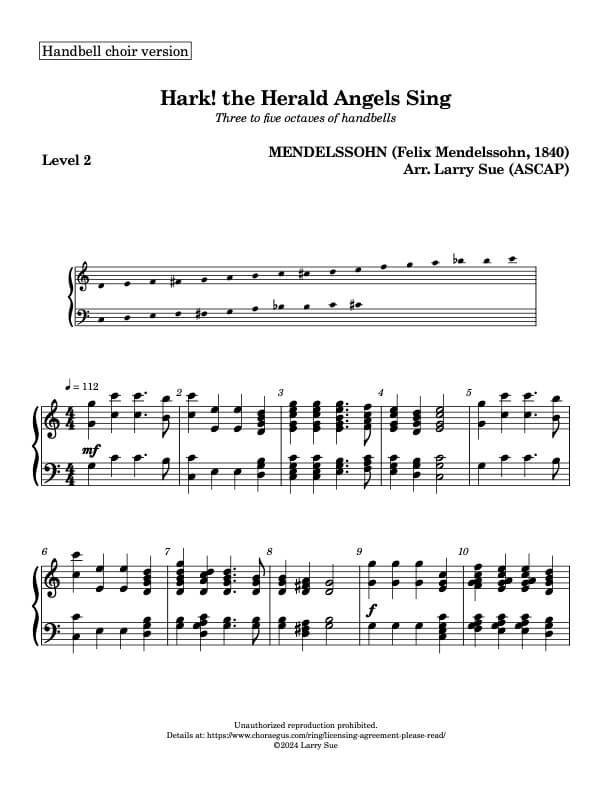

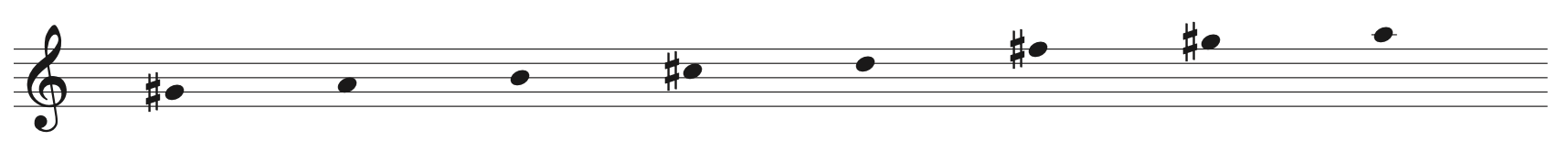

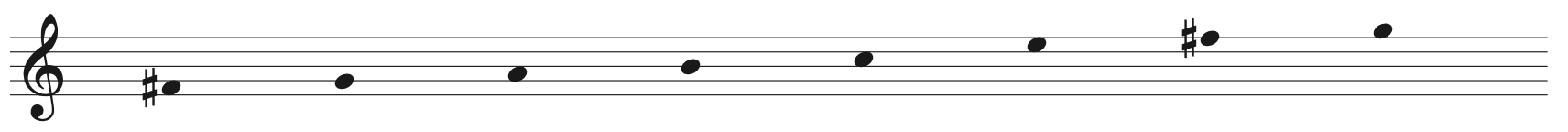

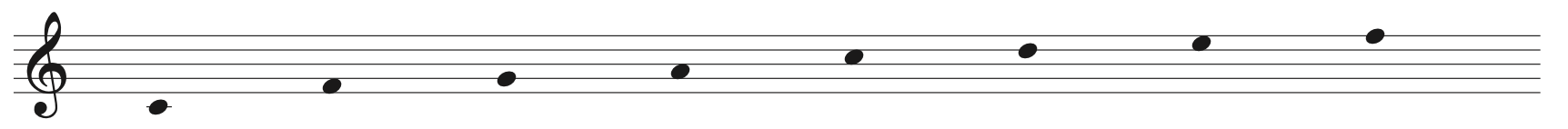

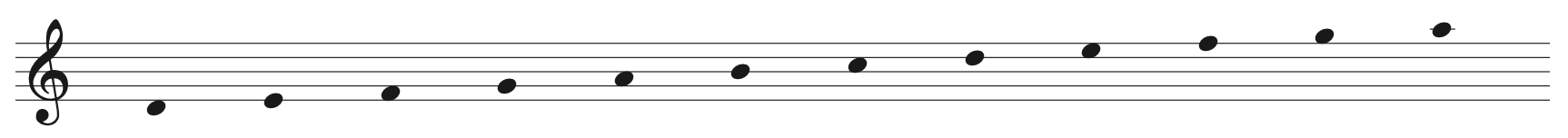

Western musical notation is based on the binary system. Here are the elements thereof (the notes are on the top staff and the rests are on the bottom staff): ?

Each note in the above illustration is half as long as the note to the left; each note is twice as long as the note to the right.

By the way, to maintain a relatively high level of sanity in the ensuing discussion, I’m going to be working in 4/4 (“four-four”) time. It’s pretty easy to adjust to other time signatures; all you have to do is remember how many beats there are per measure and which note type is equal to one beat.

If, in 4/4, you’re counting plain ol’ quarter notes, you just assign them cardinal numbers: “one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four…” If you have half notes, they get two beats, and if you have whole notes, they get four beats. Anything worth an integral number of beats is simply counted using the numbers.

It becomes a little trickier with notes which consist of fractional beats. By tradition, which means “you-don’t-have-to-count-it-this-way-but-if-you-don’t-no-one-else-will-understand-you,” eighth notes are half a beat each, so they’re counted “one and two and three and four and…” (also written “1 + 2 + 3 + 4 +”). Sixteenth notes are counted “1 ee + a 2 ee + a 3 ee + a 4 ee + a.”

You’ll note that a couple of paragraphs back I wrote that Western musical notation is based on a binary system. This is great, since it’s really simple to notate many rhythms. However, a “three-against-…” or “triplet” rhythm just can’t be done with a pure binary system (reason: 1/3 = 1/4 + 1/16 + 1/64 + 1/256 + … 1/1048576 + … forever and ever…) unless you want to sit around writing notes and ties for the rest of eternity future. So the people who invented the system also created a way to write these non-binary musical elements: all you do is put the number of equal subdivisions you want (e.g. for triplets, three) and if necessary some sort of bracket or slur to frame the somewhat uncooperative notes.

Sometimes you’ll run into sets of five, or six, or seven, or (especially in Chopin’s music) eleven, or twenty-three,… notes. The notation used to get around this difficulty is elegant and complete – the traditional convention really is quite elegant!

By the way, triplets traditionally are counted something like “one ta ta two ta ta…” For higher-order tuplets, consult an expert, or just make up some syllables… at that point, anyhow, it’s more important to say the rhythm than it is to deal with whether there are traditional syllables for that particular situation. Besides, the free-form approach to high-order tuplets could be a great training ground for learning scat jazz.

Yes, of course it’s partly nonsense syllables – but at least they’re well-defined nonsense syllables. Just so you know, the whole idea of using these preformulated syllables is to provide you with a way to associate certain rhythmic elements with certain phonemes; once you know the structure of things, it really does make life easier. Sidelight: There was a trumpet player named Alfred Harris in my senior high band. He was an excellent instrumentalist, and the foundation of his skill was his ability to count practically anything correctly the first time – as far as I remember, Al never made a counting error!

I also understand that the Shaw Chorale does a lot of work with “the numbers.” Weston Noble once told us that Mr. Shaw would have his singers count their parts for weeks on end, never letting them sing the actual lyrics until he was satisfied that they had the rhythm.

How to learn this: Grab any piece of music and work out the rhythm syllables until you can read them off smoothly and quickly. Then learn to do it at any [steady] tempo. Nothing to it, right?

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 8

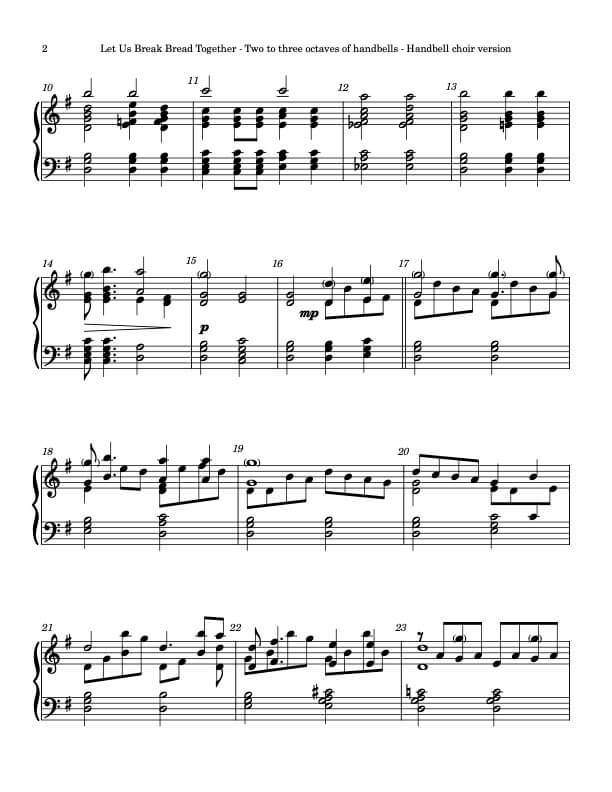

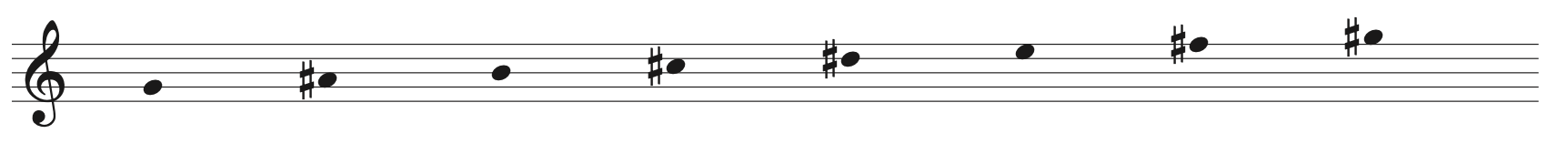

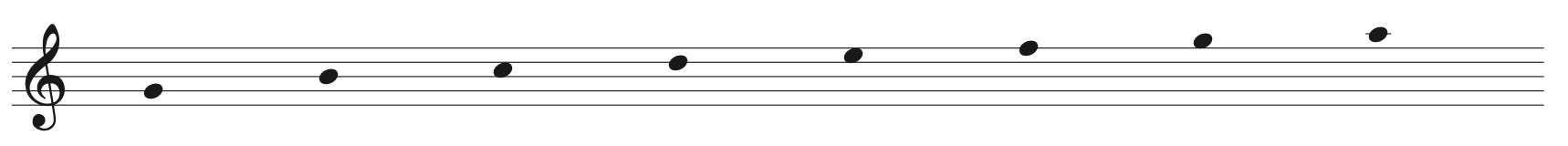

In addition to pitch and rhythm, there are lots and lots of expressive markings, such as ![]() ,

, ![]() ., and “rall.” These cover other very important aspects of the music:

., and “rall.” These cover other very important aspects of the music:

Volume:

| ff | “fortissimo” | Very strong. |

| f | “forte” | Strong |

| mf | “mezzo forte” | Medium (“sorta”) strong |

| mp | “mezzo piano” | Medium (“sorta”) soft. |

| p | “piano” | Soft |

| pp | “pianissimo” | Very soft |

| cresc. | “crescendo” | Becoming stronger |

| dim. | “diminuendo” | Becoming softer |

Tempo:

| rit., rall. | “ritard(ando)”, “rallentando” | Slowing |

| accel. | “accelerando” | Accelerating |

| <bird’s eye> | “fermata” | Hold this note/chord |

Articulations:

| <dot> | “staccato” | Shorter in duration than written (with respect to the current musical context. |

| > | “accent” | Somewhat stronger with respect to the current musical context |

| sfz | “sforzando

‘ |

Forced; played with extra emphasis with respect to the current musical context |

| marcato | “marked” | Marked (as in punchier) with respect to the current musical context. |

A lotta words in Italian, German, French, or English (mostly, but not exclusively so): More than a few composers add notations such as:

| Andante | At a walking pace |

| Vivace | Lively |

| Presto | Mucho fast |

| Meno mosso | Carnivorous moss ahead. (Well, no… actually “somewhat less [fast]”) |

The bottom line is that you’ll do very well for yourself if you pick up a music dictionary somewhere. They cost only a few dollars (three or four or five), and define most of the common terms. As for the others, you can consult your friends which might happen to know the language in question…

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9

Part 9

Sight reading skill seems to progress in levels. At first, the pitches and rhythm are enough. As your skill increases, you add the dynamics and articulations, and eventually everything else. But there’s another level. If you’re singing in a choir, you need to fit your voice into the corporate expression. Among other things, this means:

- You sing in such a way that you contribute significantly to the section of which you are a member.

- You sing so that you and your section complement the other sections.

- You know who’s singing the melody and temper your vocalizing so that their part can be heard easily.

- You grasp the harmonic structures as you encounter them, possibly adjusting the harmonic spectrum of your voice to fit the circumstances.

- You understand, implicitly, the group chemistry and function as part of the entire group expression.

The next level is to perceive what surrounds you and to contribute to it. It can be a very challenging learning experience because you need to learn how each person sounds. Work from wherever you are and aim to learn how to sight read rhythm, but think and feel far beyond the scope of your individual voice. This may mean that you have to sing less strongly – or more strongly! – than is natural for you, or that you have to execute some interesting technical gymnastics to accomplish the task at hand. Ultimately, the idea is to meld the individual members of your choir into a unified whole, which means that everyone must be making ministerial and technical progress on a continuing basis.

Sight reading is combining everything together to make one coherent whole the first time you see a score.It takes some time to learn how to read effectively. It fits into our Value statement quite nicely:

- Professional Quality In Service: Being able to sight read effectively reduces the amount of time required to learn the mere score, and gives you the advantage of being able to address the message and expressive characteristics of the music (that’s why professional singers can make their living with their voices: they can sight read anything). Once again, hereÕs my description of the ideal choir: “The ideal choir is a body of musicians from which any selection of members (regardless of sectional distribution) can sight-read any musical selection (regardless of difficulty or style) at performance quality.”

- Open-Ended Achievement: There always is room for growth. Sight-reading skill makes it possible to reach for new vistas, if not only because it represents a significant milestone in technical achievement.

- Service In Action: Being able to sight-read proficiently makes life easier for those who surround you, and can inspire others to grow as well. It also places you in a position where you can help others who are following your example!

- Unity Of Spirit: There are very few musical experiences beyond that of hearing (and seeing!) a choir which is well-unified in what they do. The attitude is evident even before such a choir sings a single note, and is obvious as they make music. LetÕs (continue to) be such a choir!