Why?

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Part 1

What you need:

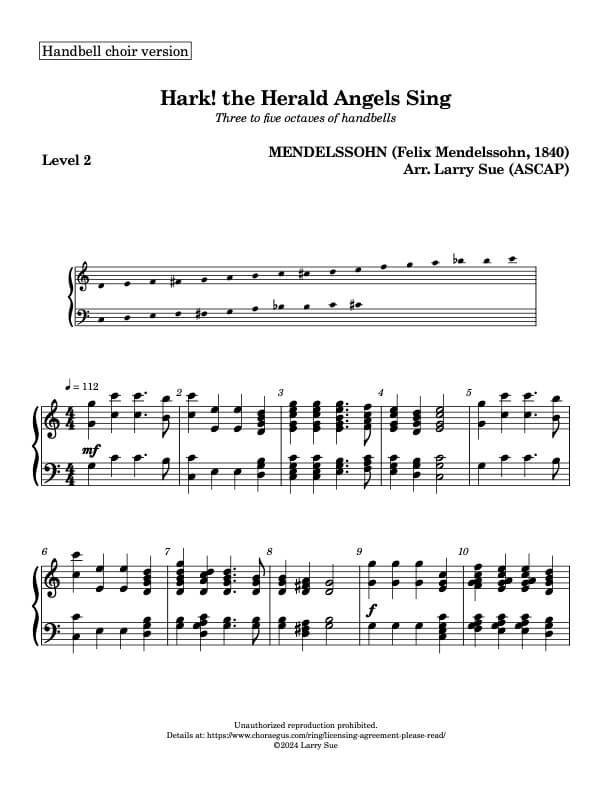

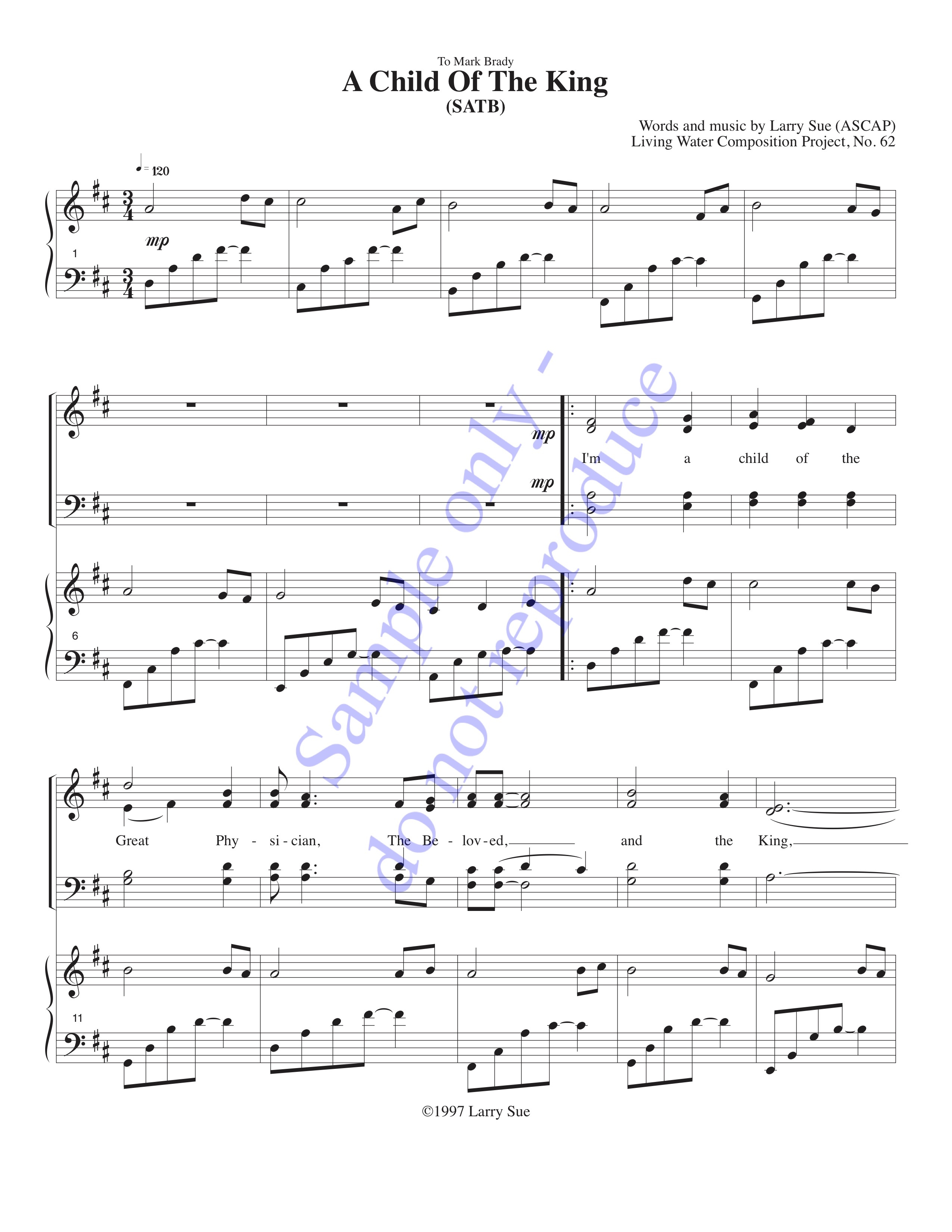

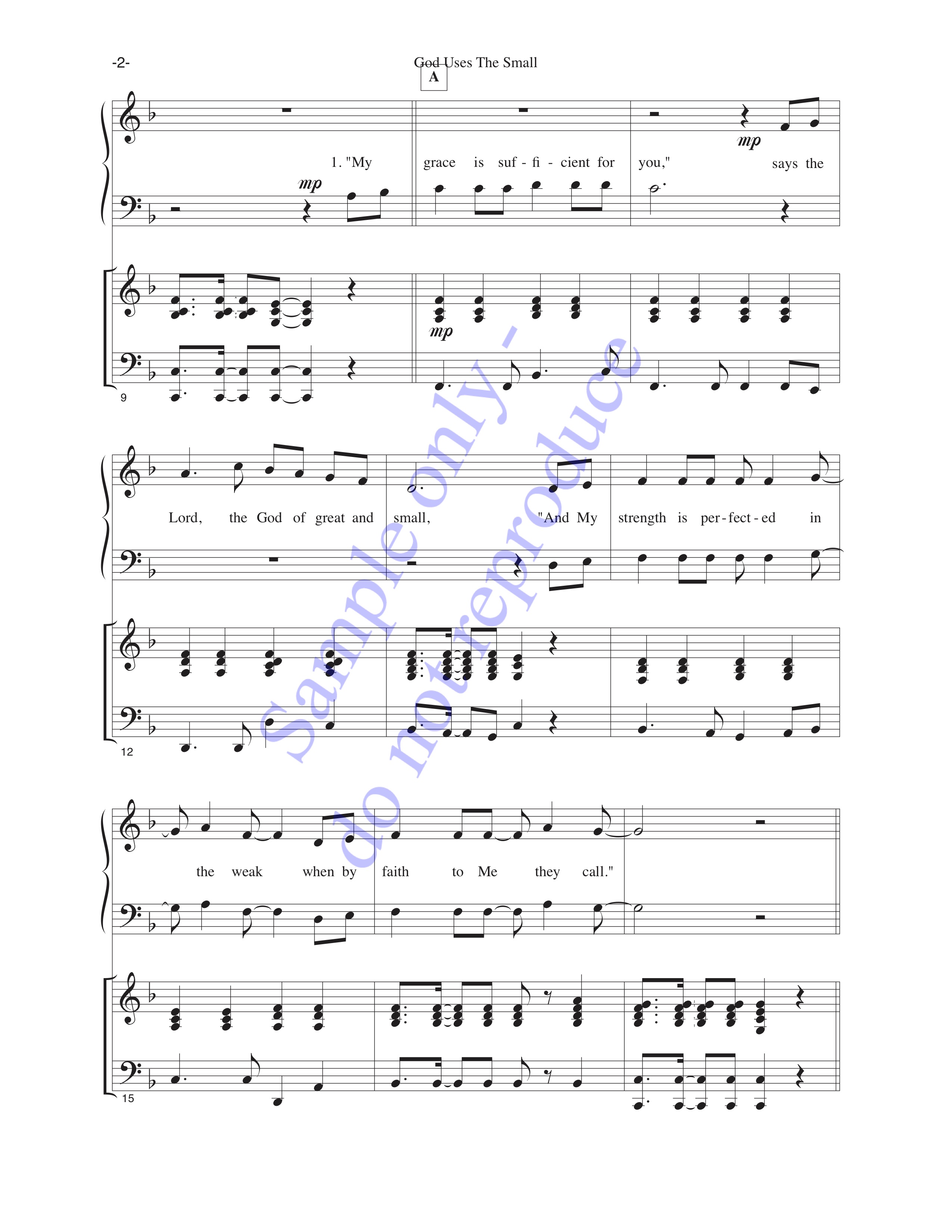

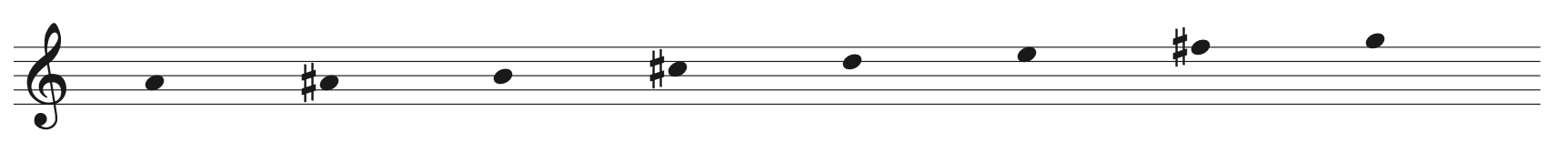

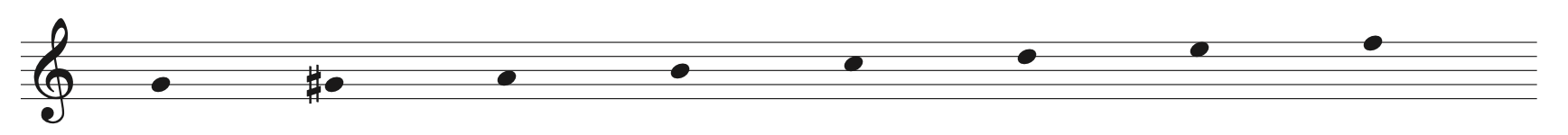

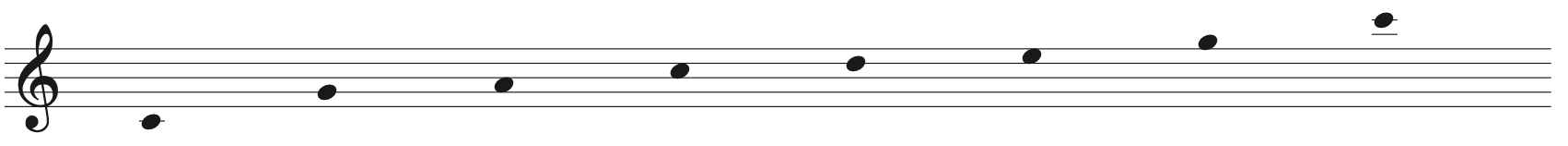

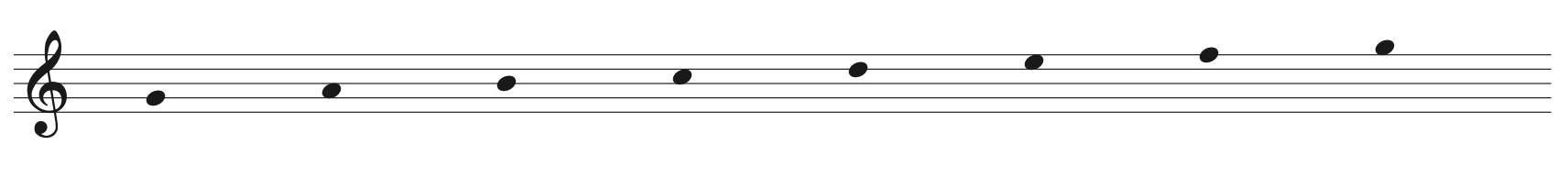

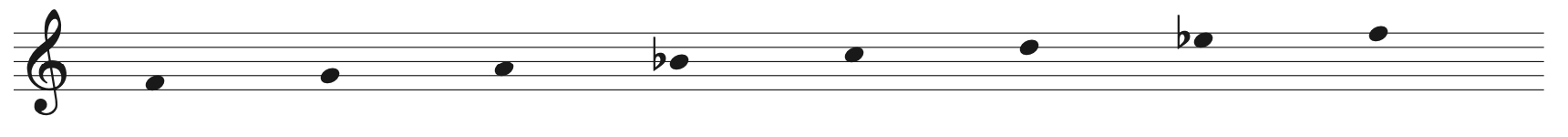

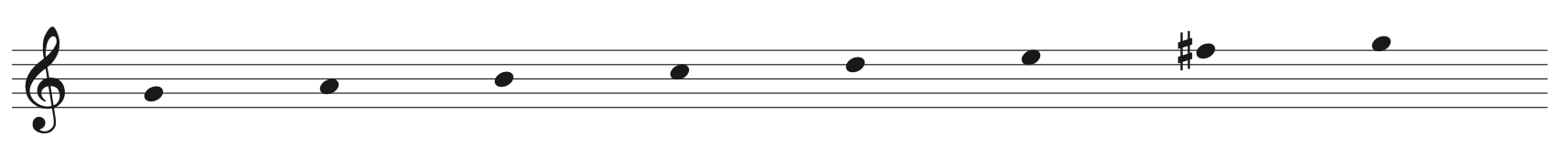

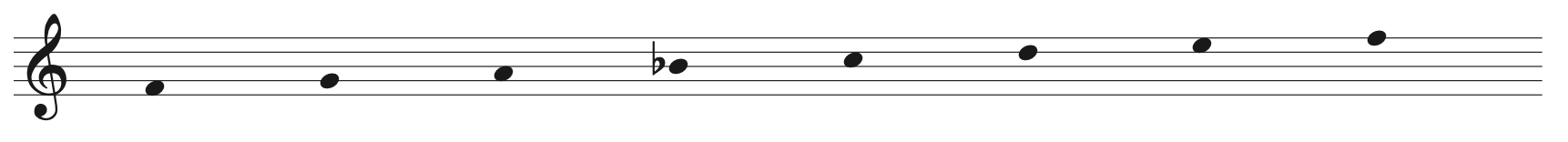

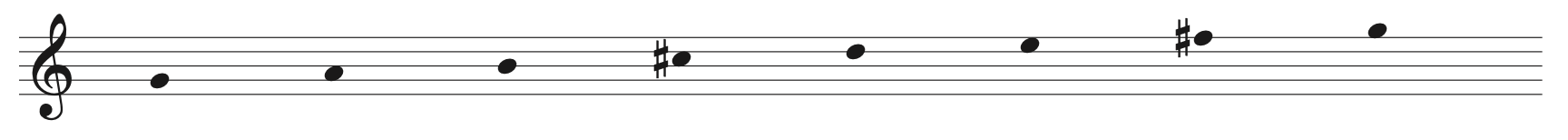

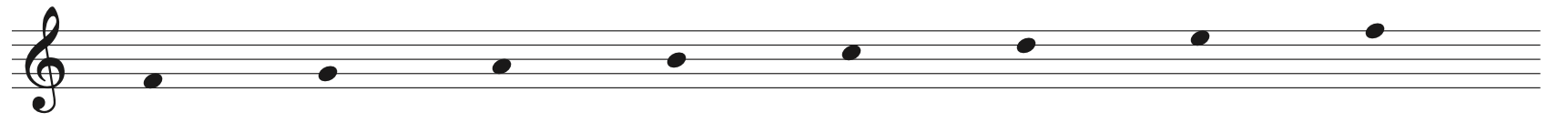

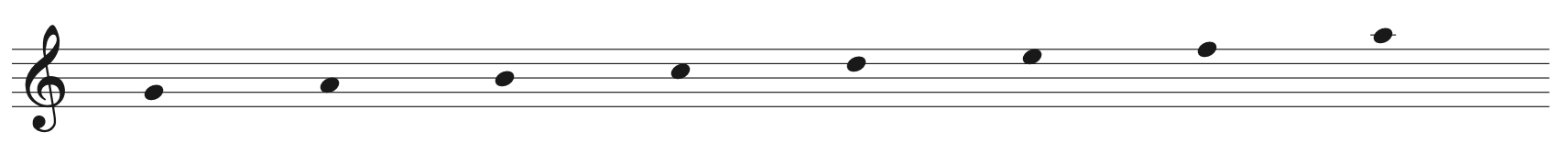

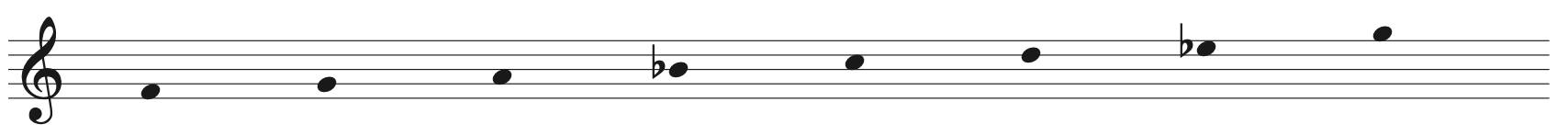

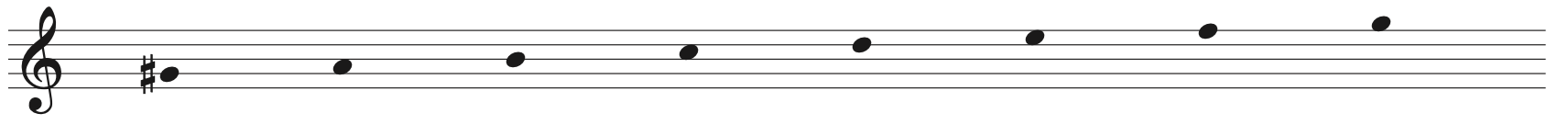

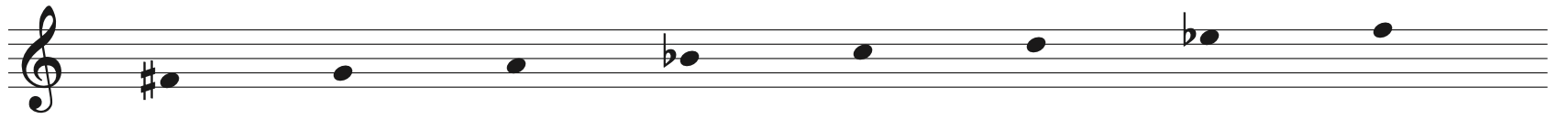

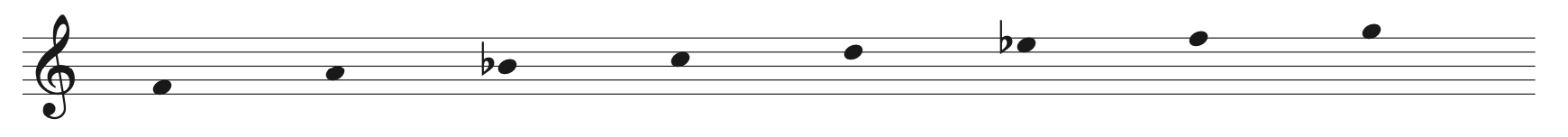

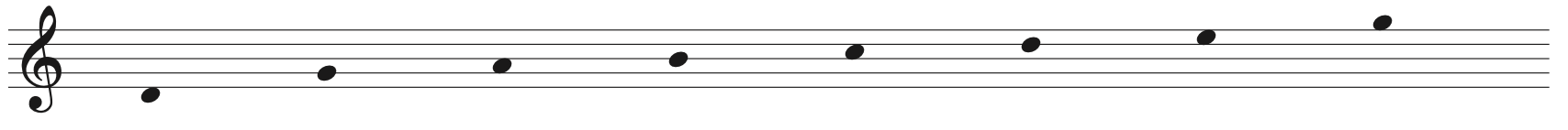

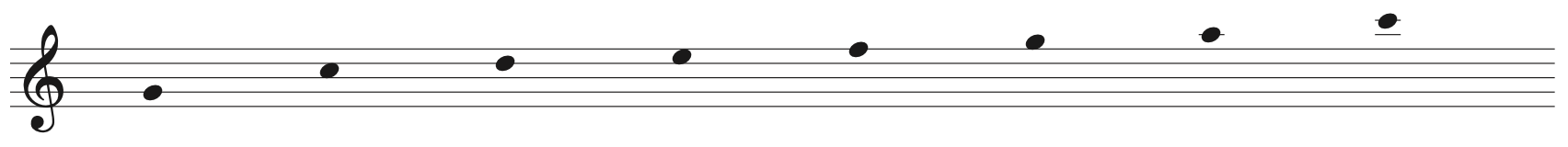

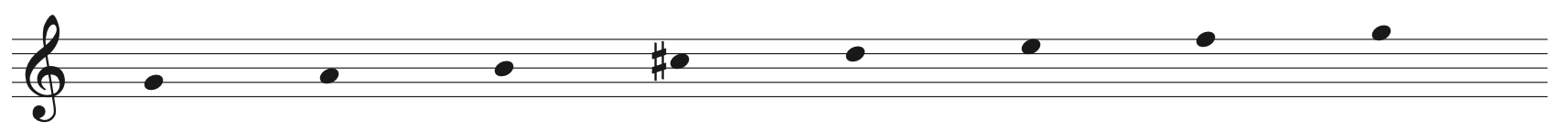

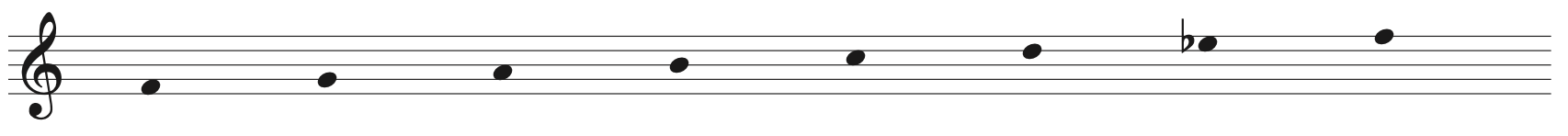

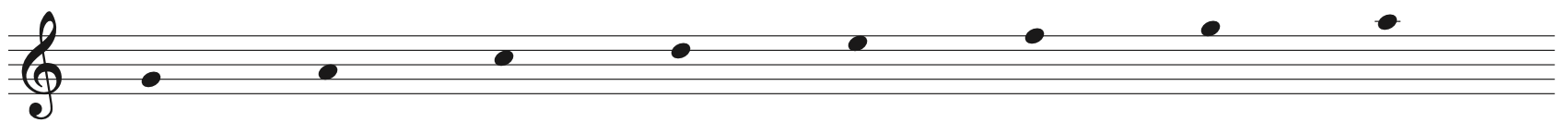

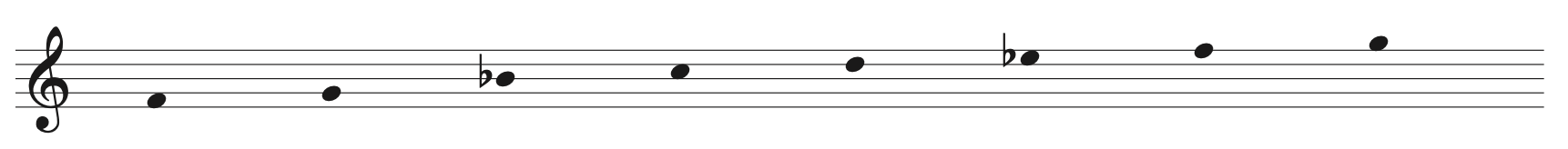

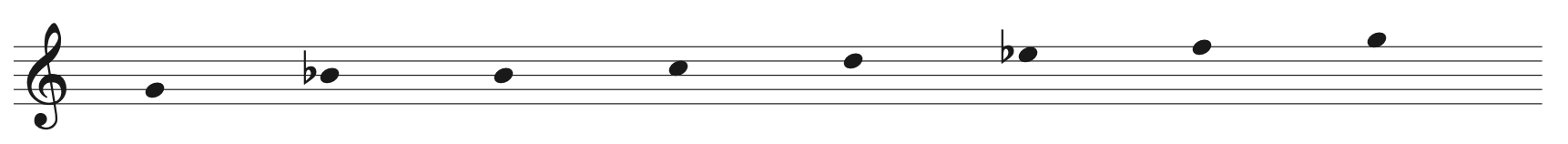

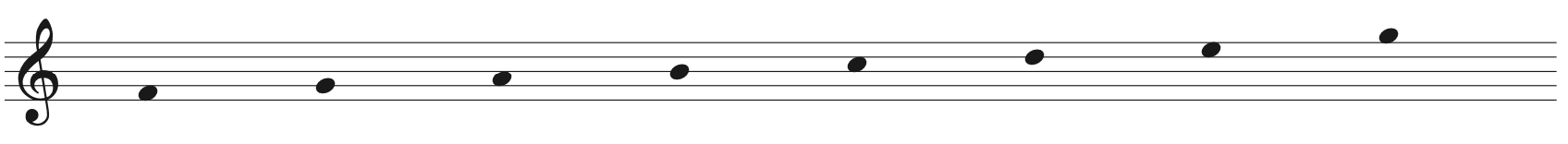

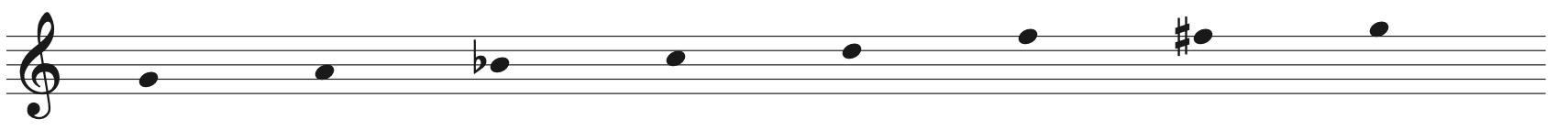

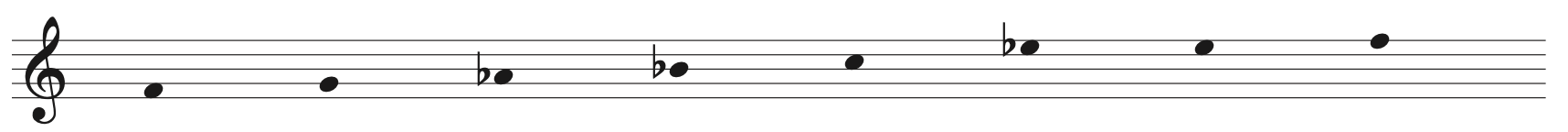

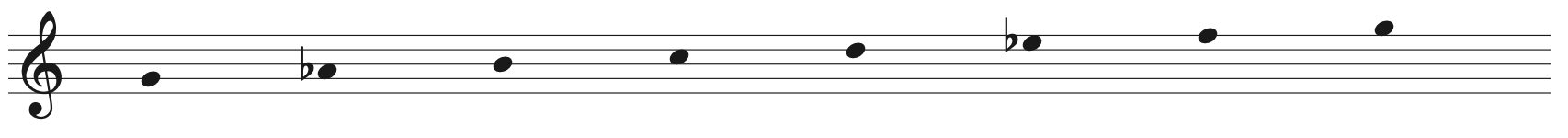

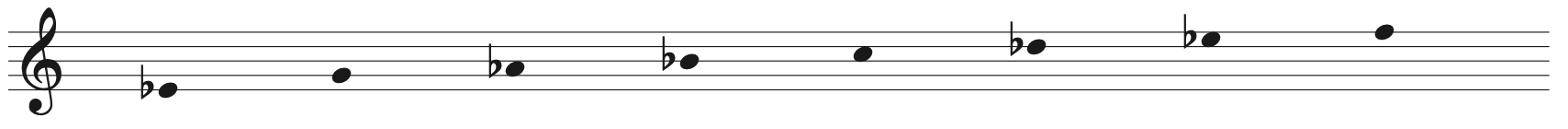

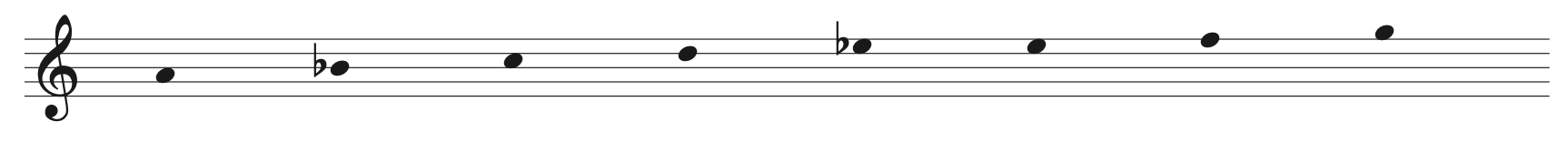

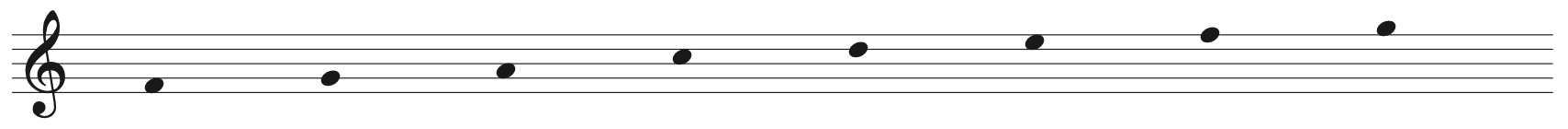

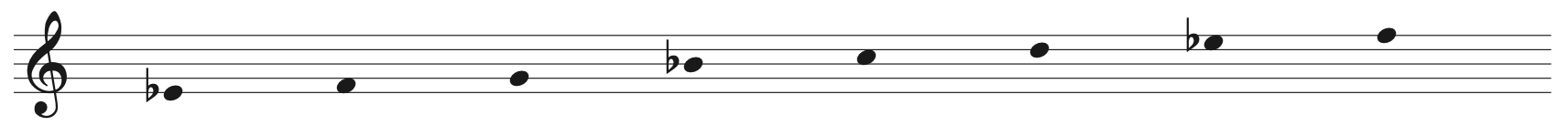

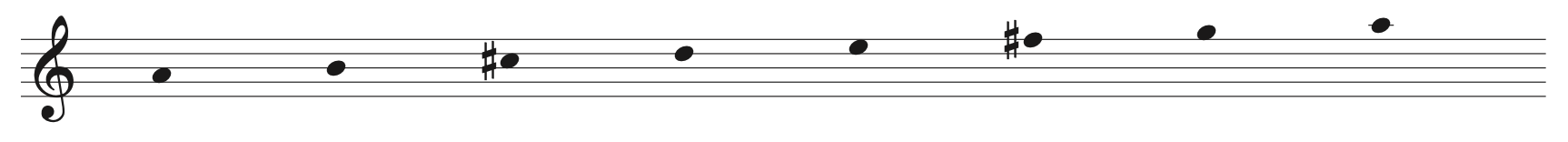

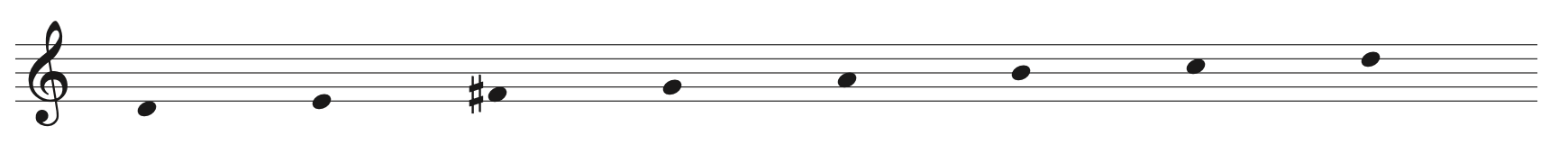

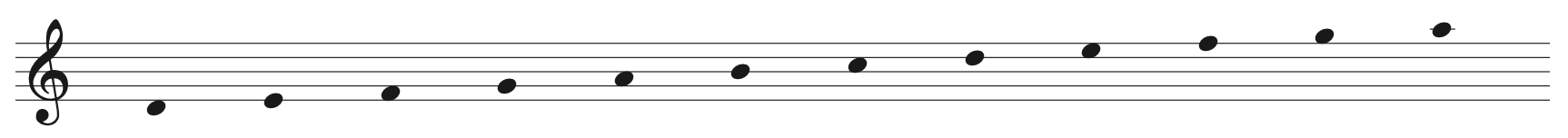

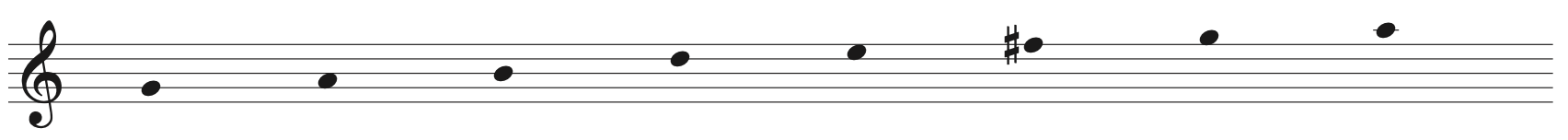

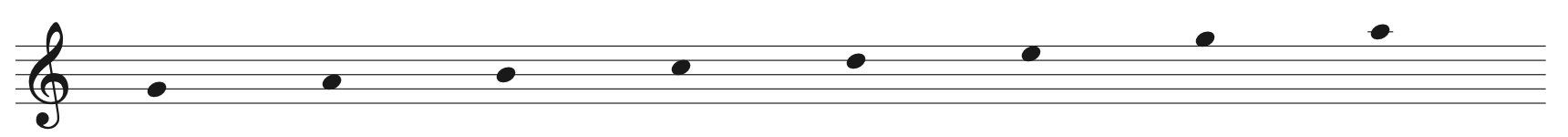

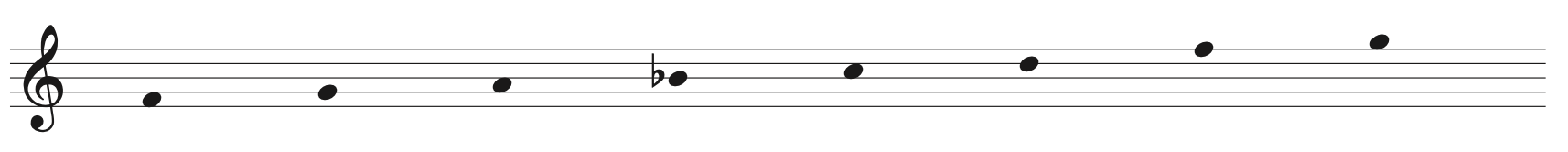

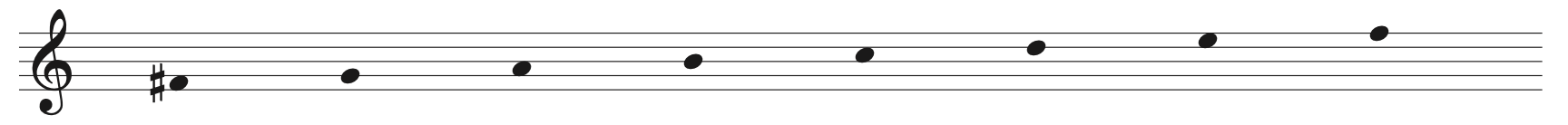

Musical literacy: It’s absolutely essential to know how to read music. Beyond that, you also need a good grasp of the special symbols used in handbell scores).

Handbell technique: You’ll need playing experience with bells (well, duh!).

Flexibility: We’re not talking about the sort of flexibility we see in Olympic gymnastics; we’re talking about mental and technical flexibility, the ability to switch gears smoothly and effortlessly with respect to the way a piece goes.

Dexterity: Solo ringing is a two-handed effort in much the same way playing the piano is polydextrous: You might find an occasional work for one (usually the left) hand, but the overwhelming proportion of the repertoire will require both (and sometimes will appear to require three) hands.

Innovativeness: Since ringing is a rather individualized skill, you need a facility in solving problems by ingenuity as well as raw technique.

Concentration: You’re the only one ringing. This means you’ll have more bells, and will have an exponentially greater need to keep track of what’s happening.

Memory: While this isn’t an absolute requisite, memorizing your solo part will make life easier by eliminating one thing you need to watch, and will increase your mobility at the table (and when you’re ringing three dozen bells, you’ll need it!).

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Part 2

Ideas

Smile!

The epitome of practically any art is to achieve a level of virtuosity such that the performance appears to be effortless. Translated: Even if it’s hard, make it look easy. One of the great indicators of this disposition is keeping a smile on your face as you play, no matter how tough the part is.

Practice hard!

Nothing will take the place of hard work, except possibility innate talent – but most of us aren’t blessed with that sort of natural skill. As someone once said, “Anyone can get an education.” Similarly, anyone can put in the required practice. You might need more time than other people, but you can still make the time investment. The key is what the sports people, among others, call “work ethic.” It’s not the people who have the great skills who succeed, but the people who greatly apply the skills they have.

Memorize!

Same deal as the last paragraph. If you’re willing to put in the work to memorize your part, it’ll pay off. Don’t worry – you won’t run out of cerebral storage…

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Part 3

Practice Techniques:

By the way, I got a lot of these ideas from one of my piano teachers; they apply well not only to instrumental music, but also to many other [nonmusical] skills.

- Practice small sections before working on large ones.

The beauty of learning a piece by small chunks is that your assimilation of the music is greatly improved. This is mostly because you can get more repetitions into a short amount of time; it’s easier to get a handle on small bits of information than big ones. For instance, you don’t memorize a whole textbook at one sitting; you usually attack it one chapter (or section) at a time. - Practice slowly, then up to tempo.

Solo ringing requires development of complex motor skills and perceptions. Consequently, never allow the practice tempo to exceed the speed at which you can play the whole passage properly. After you’ve worked it out at one speed, increase the tempo a notch at a time (use a metronome!) until you reach performance speed. - Try “air bells.”

Without using the physical bells, take the music and try playing through it, making all the necessary motions to simulate playing the actual piece. Be diligent, however: it’s too easy to allow this to become a half-hearted exercise in hand-waving – make the full reach each time. (This method also allows you to practice when you’re not with the bells – and it helps develop the coordination you need.) - Try mental practice.

Go through the score mentally (by memory?), trying to feel the actual movements you’ll need to make so that you know when they occur and how they feel. A note: this method of practice doesn’t look as silly as “air bells” might…

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Part 4

Final Thoughts:

Enjoy yourself. Well, unless you’re a masochist… Regardless, though, remember that it isn’t real ministry if you’re not having a good time. So rejoice!

Be patient. Solo ringing takes more time than regular bell choir work because of the additional (exponential?) intricacies. Take the time to work slowly and carefully, and don’t rush the performance date – it’s better to postpone a shaky number and do it right a little later than expected than to go out there and feel/look like an idiot. Quote from Cynthia Dobrinski: “The important thing is not to look spastic.” (Mount Hermon, June ’96)

Innovate. Try new ideas, especially those which may have been thoughtfully provided to you in the score. On the other hand, if something looks as if you can invent a better way to play it, try your idea. Who knows – you might be responsible for the next major advance in handbell technique!

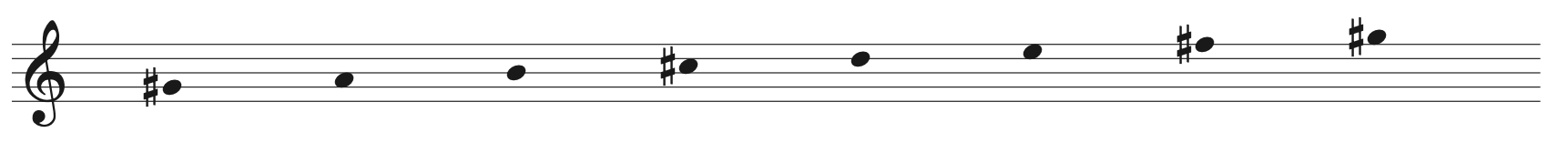

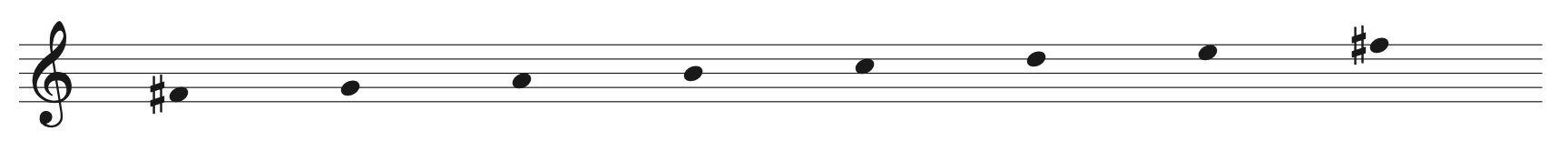

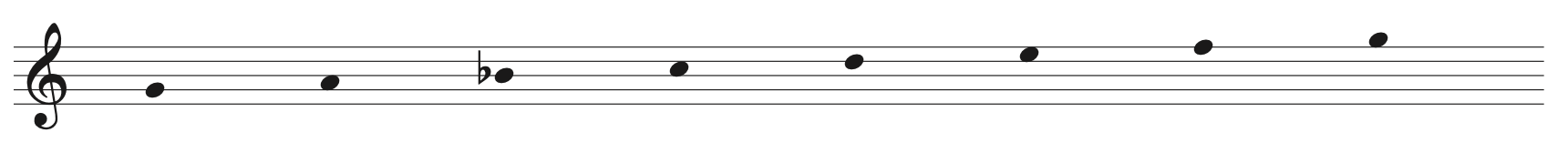

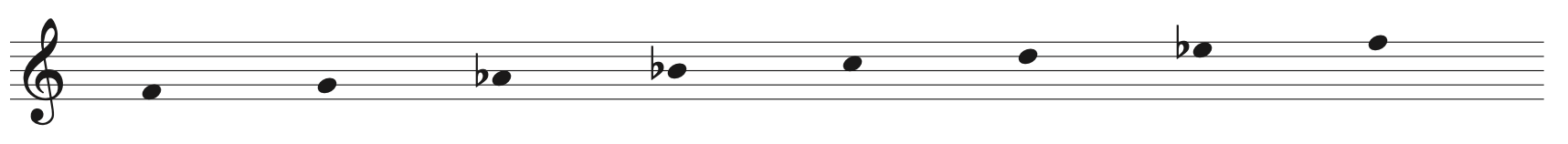

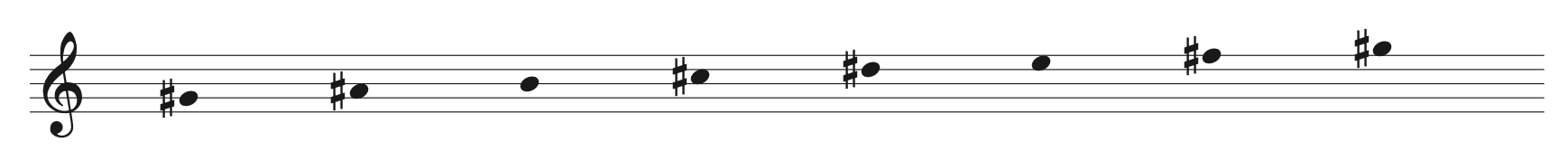

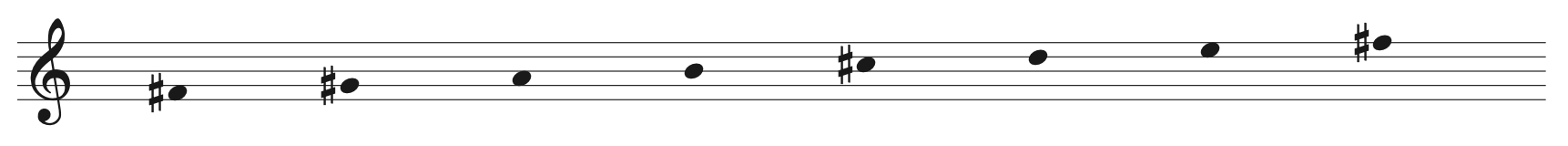

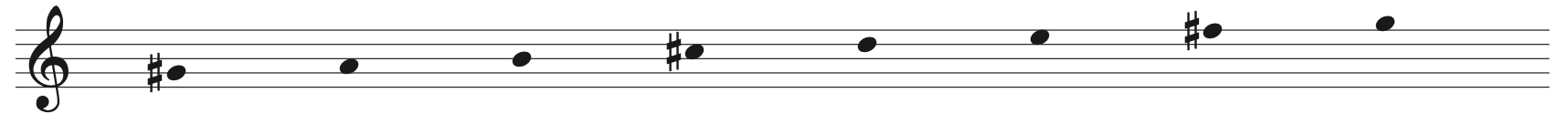

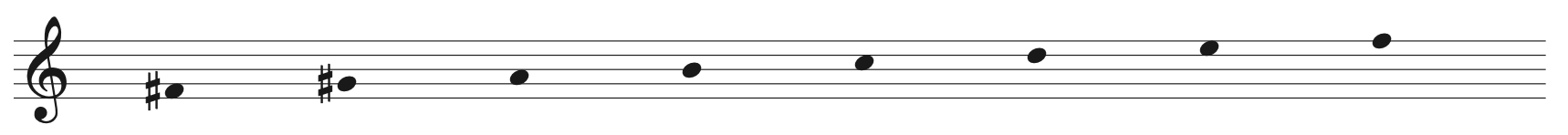

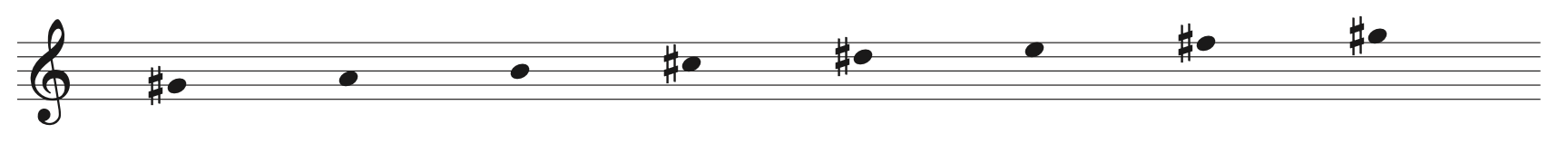

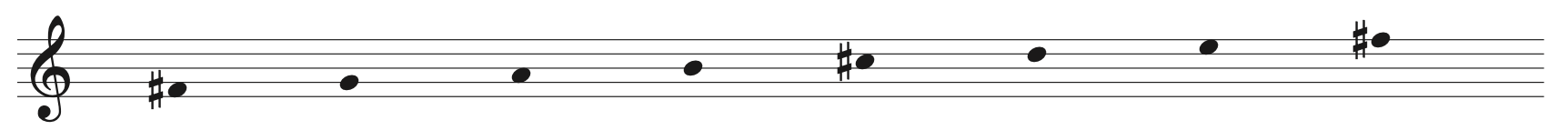

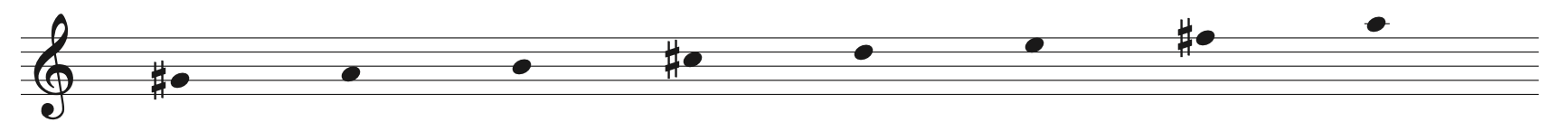

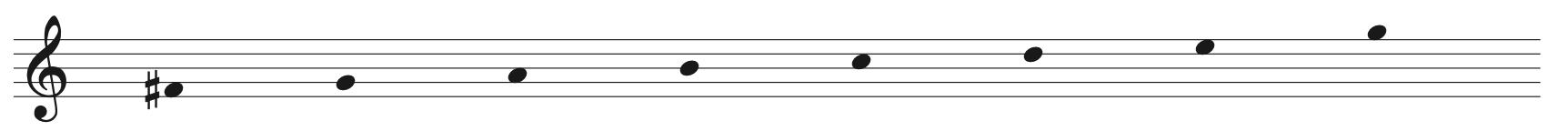

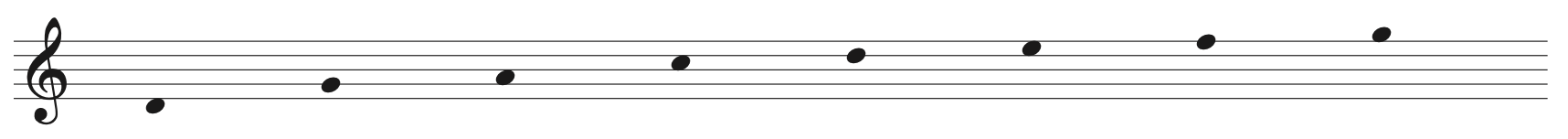

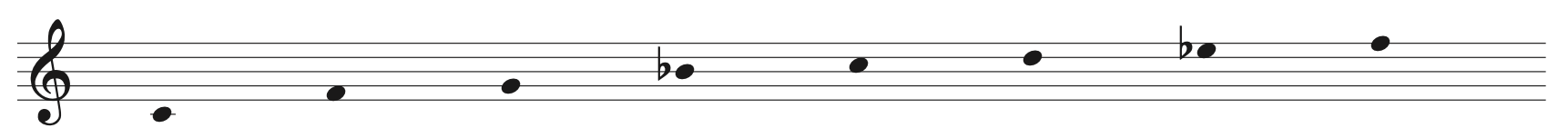

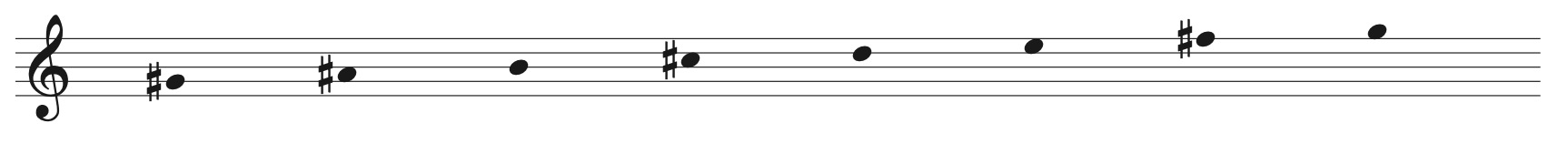

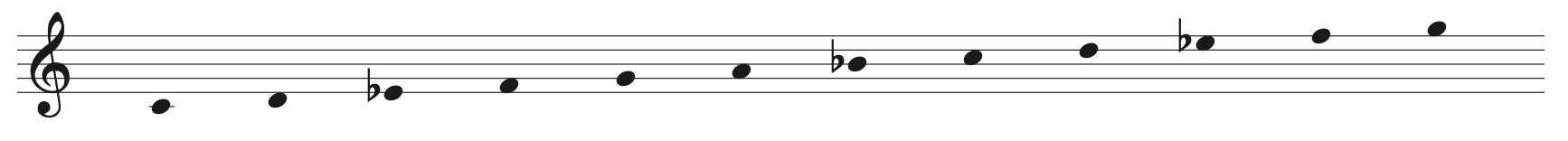

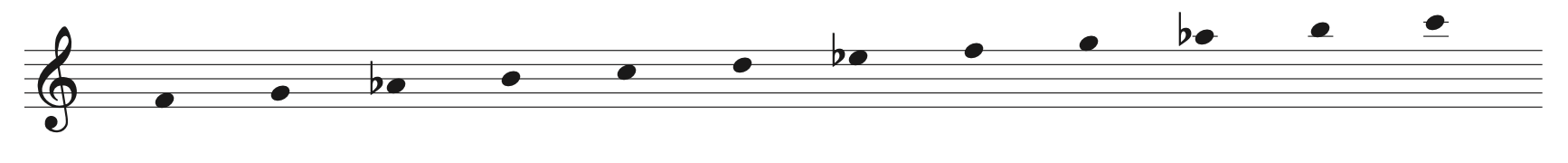

Learn. Remember also that solo ringing can be an incredible learning experience because of the skill level involved. You probably will be mislaying bells, playing four-in-hand and Shelley, and maybe even slipping in a hook or two as you go through your selection. So enjoy the opportunity to expand your horizons!

Encourage others as they walk the path. Be willing to play a mentor’s role if someone else asks you for help. You can only make the ministry better. Remember: Ideas grow if shared.