The following is from a series of articles I wrote for Living Water, the choir I directed at Valley Church (Cupertino, CA) from 1987-2003, and at First Presbyterian Church (Mountain View, CA) from 2003-2011. While Living Water is no longer in action, the ideas I had the opportunity to present are just as valid now as then.

I made my first attempts at composing music when I was a teenager, and it was really frustrating to try to create a musical work without any sort of idea of what should go into it. Over the past couple of decades, I’ve learned a few things which I’ve found to be useful in writing songs (the most important, of course, is to go and do it so that you can get some practice…).

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 1

Over the past two years (this was from a series of letters to Living Water during our 1991-1992 season. It followed a huge flurry of songwriting activity which eventually became Volume 2 of the Living Water Composition Project, bringing the total number of compositions to thirty), I usually have spent some letter space in educational mode. Topics have included my personal philosophy of ministry, MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), and choral diction. My intent in writing on these subjects is to offer you a view of the choral/music ministry which goes beyond casual acquaintance with serving God. It’s tied to the Living Water Vision and Values with which you are all familiar (“Glorifying God and causing others to do the same,” “Professional Quality in Service,” “Open-Ended Achievement,” “Service in Action,” and “Unity of Spirit”).

My hope for the Valley Church music ministry is that we can develop an abundance of leadership and skilled servants of the Lord who can be used throughout the whole body of Christ for the glory of God (now, doesn’t that sound like Paul the apostle?). Whether those who are trained at Valley stay or eventually move on to other local church bodies is only a small concern – the important thing is that we learn how to serve God and that we do it effectively.

On to my topic for the next few months: I’ve noticed that the Lord has been producing some interest in composition. I’d dearly love to see a bevy of Valley Church composers come to the fore, and I’m willing to do what I can to build them up if God grants me such a ministry. So we’ll be taking a look at the various aspects of composing music, including the parts of a song, possible education which might be useful, and even what’s involved in finding a publisher for your music.

My own compositional background is that I’ve been making attempts at composition since I was about fourteen or fifteen. The first ones weren’t so good; they were mainly repetitive and boring, not to mention devoid of harmonic imagination. Nevertheless, the Lord provided me some opportunities to write and sing a few (somewhat better) songs at the Chinese Independent Baptist Church in Oakland. Eventually, at the church we attended before coming to Valley Church, I had the privilege of doing some arranging and even a little composing for Christmas cantatas and some special numbers.

Coming into the music ministry at Valley Church was a splendid opportunity for personal development because of the sheer number of choirs and groups. Tom Shedd, our former music minister, wasted no time in getting me into Sanctuary Choir, Worship Team, and Alpha Tau Pi (the men’s quartet). He asked if I’d be interested in directing Living Water, and I accepted – all this happened in about half a year!

LW and the quartet, in addition to the ladies’ trio and the Valley Ringers, have provided more than ample opportunity to learn the craft of writing music. Dave Ruder and I now constitute the membership of the “Valley Church Sadistic Composers’ League,” a semi-fictitious group which has the unfortunate tendency to write music of such difficulty that it might as well be written for piccolo, tuba, and tambourine with all notations in New Testament Greek. Nevertheless, I think I’ve been becoming a little more humane in my compositional treatment of accompanists and vocalists (that, I guess, is a way of saying, “If you think the current stuff is difficult, you should have seen some of what preceded it”)!

I greatly appreciate the Valley Church family’s tolerance / acceptance / appreciation of my songwriting. Some of the stuff has been a bit weird (e.g. the first couple of text lines in “Walk Beside Me”), some has been almost overblown (the big-band quartet arrangement of “Trusting In Jesus”), and some has been tortuous in nature (“Worship!” where the final chorus line is “serve the eternal King, Alpha, Omega, the Mighty God and Wonderful Counselor, Prince of Peace always with all your heart”). Things appear to be improving constantly as I inflict by musical persona on your psyches and ethoi (plural of the Greek “ethos,” which in the literary sense indicates the emotional aspect one’s being.).

I’ll finish this now over-long section of this letter by answering the question most asked when referring to writing music: “Do you write the words or the music first?” Answer: It depends. Sometimes the words come first (“This New Commandment”); other times the music forms itself before anything else (“Choose”). On occasion, both come at the same time (“He That Dwelleth In the Secret Place Of God”). Over the last year, however, I’ve been concentrating a lot more on producing the text of a song first because, after all, it’s the message I’m trying to communicate. I’ll continue this next letter!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 2

We continue our discussion on composing. This will be the second installment in what appears to be a series of eleven segments, so we should finish somewhere around March. Remember that I’m describing this subject from my own point of view – so Jackie Sackman, who is a composition major at San Jose State, and Annette’s dad, who is a published handbell composer, can keep me honest in much the same way I relied on Phil and Steve when I was discussing MIDI a few months back.

My primary consideration over the past year or so has been lyrics. The reason for this is that lyrics carry the message of a song. In the realm of Christian music, this is even more important because they present the doctrine which is to be communicated. Since II Timothy 2:15 tells us to study the Word of God so that we may handle the it accurately, there is a tremendous responsibility which we’re to fulfill if we write music.

The first goal, therefore, is to write words which not only glorify God, but which glorify Him accurately. This applies to everything we do, but even more in music. The reason for this is that many people, myself included, can fall into the trap of appreciating the music before we understand the words. Music which is great (in terms of communicational impact) has a way of inducing us to accept whatever text accompanies it without thinking a whole lot, and if the song is teaching heresy, or is not teaching the full truth, it might happen to slip by as we enjoy the orchestration supporting the lyrics. My personal view: “Good music with bad lyrics is like perfume in a cesspool.”

I admit that it might be possible to be overly picky in this respect. Even some of the great hymns contain doctrinal questions (not necessary flaws!) if you beat on the words hard enough. For instance, in “And Can It Be,” what precisely does the phrase “emptied Himself of all but love” mean? “Emptied” is found in Philippians 2, but it doesn’t specify that of which Christ emptied Himself. To this you may say, “Picky, picky, picky” – and you’re right! The greatness of Christ’s willingness to humble Himself that He might save us from our sin is presented dramatically, and only the hypercritical doctrinaire will be completely unable to enjoy the hymn. Nevertheless, I still prefer to be very self-critical as I write lyrics because I know this is part of the teaching ministry that God has given me. So I want to ensure that my words are fully in accord with Scripture.

Also, I’d recommend that you work and rework your lyrics to remove any extraneous words. There’s a certain freshness in lyrics which convey their intent with a minimal set of words. “Jesus Loves Me” happens to be a very profound and elegantly-written hymn – take a look at the verbal economy in it!

Clichés are also something that I try to avoid in my song texts. The reason for this is that clichés are expression which have become so common that they’ve lost their original impact. Because of this, I believe that incorporating a cliché in a lyric gives the listener an excuse to turn his brain off for the rest of the song. Finally, I hope to avoid phrases which can be misinterpreted. This seems to be very difficult to do because I have my own blind spots and probably miss some implications which my words contain.

Idea: when you write your lyrics, it could be very helpful to show them to someone. You might even want to select someone who doesn’t know you at all well so that you can have the advantage of a fairly unbiased view (a good friend might understand your words to the point where absolute textual clarity may not be required – he/she might have some of the same blind spots!). I’ve done this before, and it’s given me a better idea of how to look at what I write.

Next time, I’ll continue the discussion on lyrics. If you thought it was tough to write good words, then writing good words which go with music…

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 3

We continue our discussion of lyric-writing with the topics of rhyme and meter. Rhyme pattern is one of the aspects of lyrics which cause them to stick in our minds. Think of the next line for these examples:

- Twinkle, twinkle, little star,…

- To God be the glory, great things He has done,…

- Here we come, walkin’ down the street,…

- Food, glorious food, hot sausage and mustard,…

You probably got at least three of the four without difficulty. Part of the reason that this works well is that the next line in each song rhymes with the line given. Our poetic experience causes us to have an easy time of recalling words which conform to a pattern which, in these cases, is that the last syllable or syllables rhyme. The rhyme scheme in these songs is “aabb,” that is, the first and second lines rhyme and the third and fourth lines rhyme. This is probably the most common pattern in use in contemporary music. Among other things, it’s relatively easy to generate and is therefore well-suited to the “tune factory” approach espoused by many people in the entertainment industry.

Bear in mind that this isn’t the only possible rhyme scheme. Others which work very nicely, but which are correspondingly more difficult to produce, are: abab, aabccb, aaabcccb, and abcbdbeb. The primary reason these are more difficult to create is that they require much more foresight and planning than aabb does. A second reason is that if you try to use more than two rhyming words in a scheme, you will often find just the right wording for one line, only to discover that you can’t find two or three other words which both rhyme and which can be used to make sense in the entire lyric (this probably means that you never, never should use “orange” as the last word in a rhyming line…).

There are other schemes, some of which don’t even rhyme at all. For instance, many of the classical works take a Bible text and set them to music (e.g. Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” from the Messiah). This is also done occasionally in today’s music (e.g. “Believer’s Creed” by Mark Hayes). Sometimes a pattern such as aaabcccd is used, and other times the last line of each set of four is identical from one verse to the next.

Line length is a concern in lyrics. If the lines are too short, it’s hard to communicate an intelligent message; if they’re too long, the rhyme scheme may be lost in the syllabic shuffle (I’ve been found guilty on both counts at one time or another). There’s a balance which must be established between quantity and quality.

In addition, most really good songs with multiple verses have identical syllable rhythm between verses. This attribute of good lyrics makes them easier to master because the rhythmic content must be learned only once, after which full attention can be paid to the words just look in a hymnal and you’ll see what I mean). Of course, some minor variation is generally tolerated, such as using a pickup eighth note for “the,” but drastic divergence make the song very difficult to sing well without loads of practice.

We’re not quite done with lyrics yet. Next time we’ll look at word density and borrowing words from other works.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 4

“Word density” is the amount of verbiage per unit time, that is, the number of syllables which the singer is required to enunciate per second. Lyrics should be written with syllable speed in mind. You can’t generally force singers to sing at an allegro, one-syllable-per-sixteenth-note speed for prolonged periods of time (that’s about eight syllables per second). It turns out that a normal comfortable reading speed is about 300-500 words per minute (about five to eight syllables per second). A comfortable speaking speed is about 150-200 words per minute (two to four syllables per second). And a comfortable singing speed is somewhat less than that range because of the additional effort required to pronounce words with specified pitches. In general, composers should be careful about writing music which has too high a word density because the singer might not be able to handle the pace – or the audience might not understand what’s being sung.

Another contributing factor to word density is “syllable complexity.” This is basically the way in which consecutive syllables interact with each other. “Thou art worthy” is a lot easier to sing (or say) than “The sixth sheik’s sick sheep…” This isn’t normally a consideration to most composers, but if the tempo is a fast one it would be worth singing through the piece as you write it and after it’s finished to see if there are any syllabically difficult sections. This, of course, doesn’t mean that you have to remove or rewrite them, but it might provide some motivation in that direction.

An example of extreme word density (on the high end of the scale) is Frank Mills’ “Music Box Dancer,” to which I’ve heard the words only once and which I therefore don’t remember. However, it also is one of the songs which I had the opportunity to parodize some years back. Some of you have seen the words to the parody; the second verse begins:

My volleyballer is a girl with makeup that’s smeared,

Her pretty face hits wood and so her features are weird,

But that’s because she’s keeping her glass eye on the ball

And doesn’t see the bleachers into which she will fall.

Another aspect of lyrics related to word density is “message density” – how much do the words say with respect to the amount of music presented? This is a really difficult question to answer in general because there are so many different types of songs. For instance, praise choruses tend to have low word density, and their message density is a bit on the low side because their texts are usually short and repetitive.

Classical anthems (perhaps in the style of Brahms) have rather low message density because they stretch short texts over miles of paper, but also can have medium to high word density because of text repetition.

Hymns usually have high message density and moderate word density. Of all the song types, they probably are the most efficient with respect to information communicated in the amount of space occupied.

You’ll want to consider message density as well as word density as you write your lyrics; these factors go a long way toward determining whether you’ll be able to say what you want to say in the space you provide in your song framework.

One more thing: You should generally tailor your lyrics (and song) so that the total length is on the order of three minutes, at least if you’re writing the kind of music which would be sung in a church service. There are numerous exceptions to this guideline, but I find that Gloria, the person who programs our Sunday morning music, usually allocates three minutes of service time for each musical element of a service.

Oh yes – it’s also okay to use lyrics (and music) from other songs PROVIDED YOU OBTAIN PERMISSION FROM THE COPYRIGHT HOLDER. This, of course is no problem for public domain songs, but it could require payment of royalties and signing a copyright authorization contract in many cases. By the way, Romans 13:1ff tells us that we have to think of this and act on it!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 5

Now that we’ve covered some aspects of writing lyrics, we’ll move on to music. While I realize that some songs are written music first, I had to pick an order of topics. So, with apologies to those of you who advocate writing music before lyrics, I continue.

Probably the most important aspect of music is found in the vocal parts. It usually is a lot easier for a keyboard person to play the accompaniment than it is for the vocalists to sing their lines. The reason for this, of course, is that a pianist/organist/keyboard player doesn’t have to worry about being in tune as long as he/she plays the correct keys. However, a singer must sing in tune in addition to mastering rhythm, tone, and style.

This means that, above all other things, music in a song must be singable. This is a broad enough subject to require two letters’ worth of declamation, so you’re getting the first installment on singability right now; the other installment will be in the next letter.

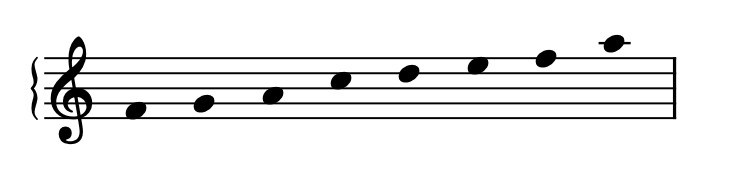

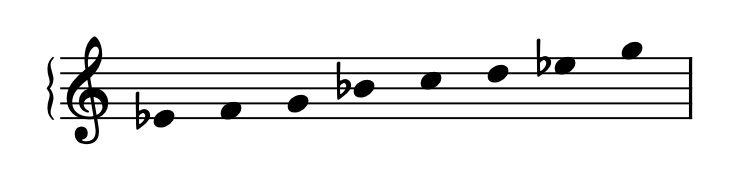

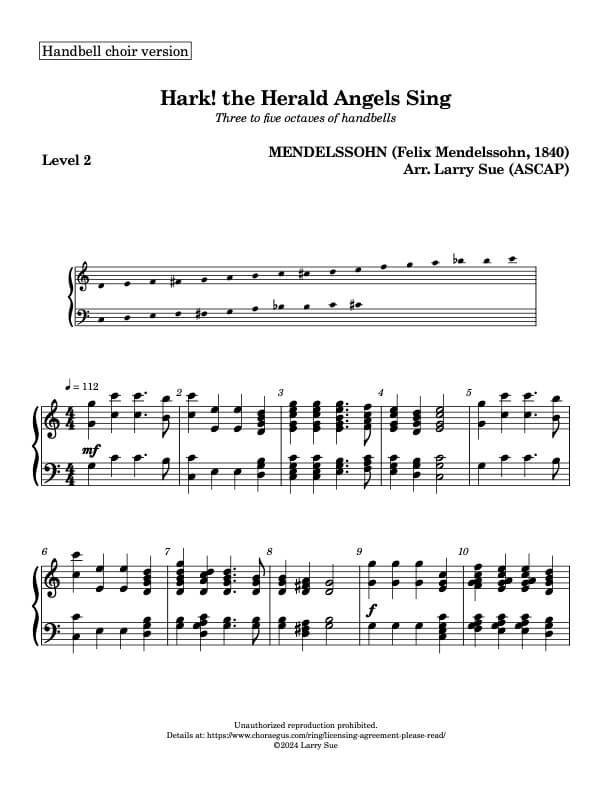

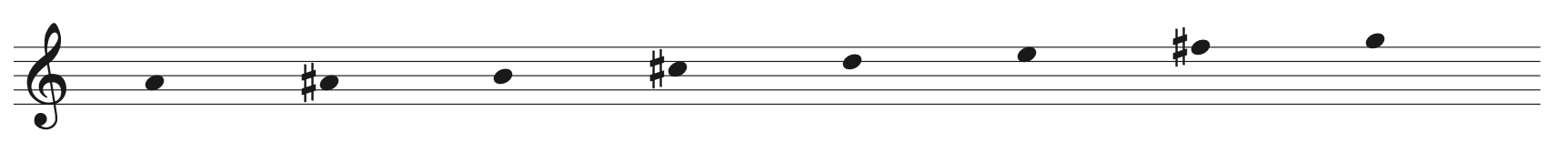

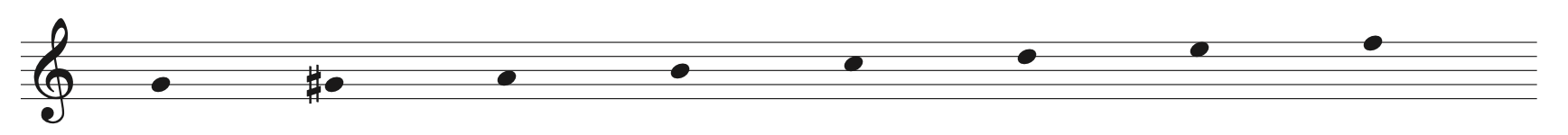

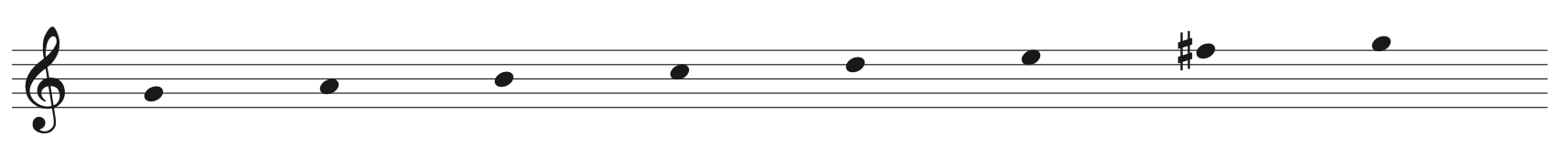

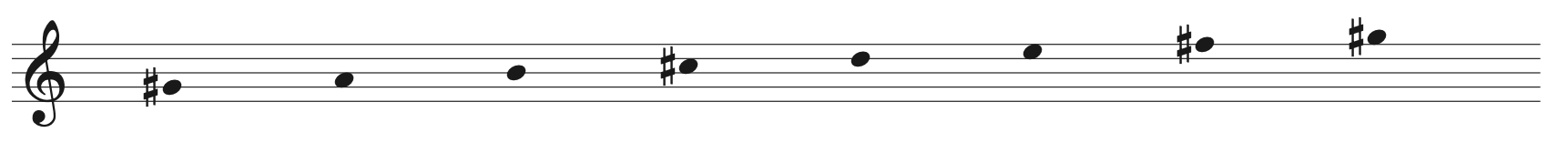

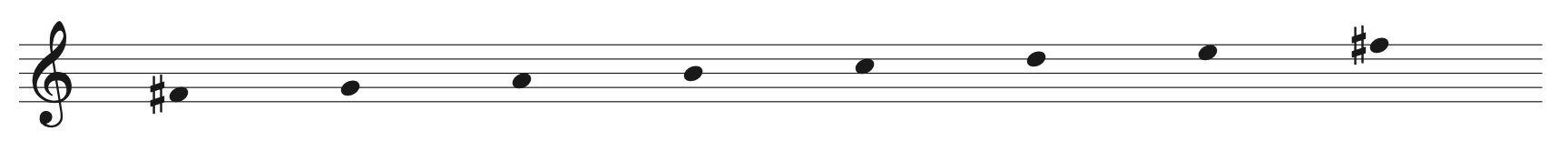

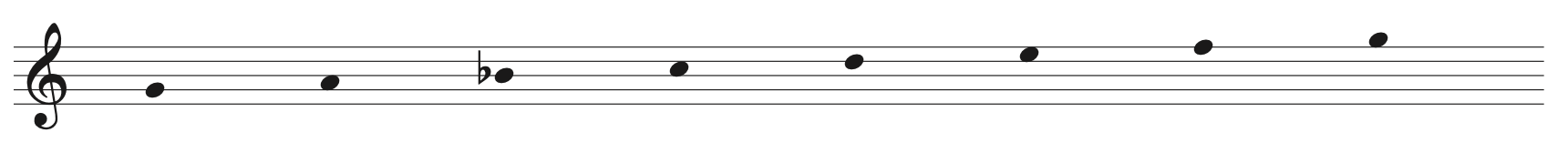

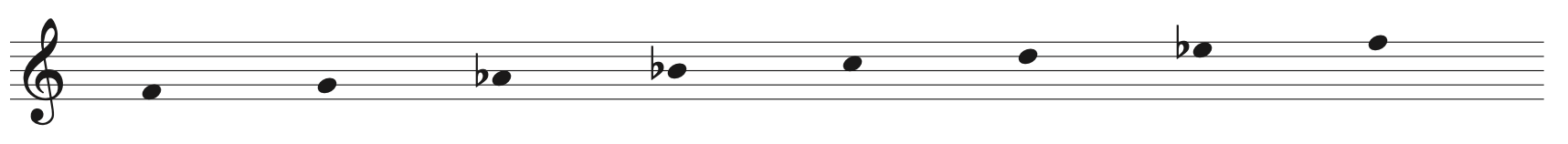

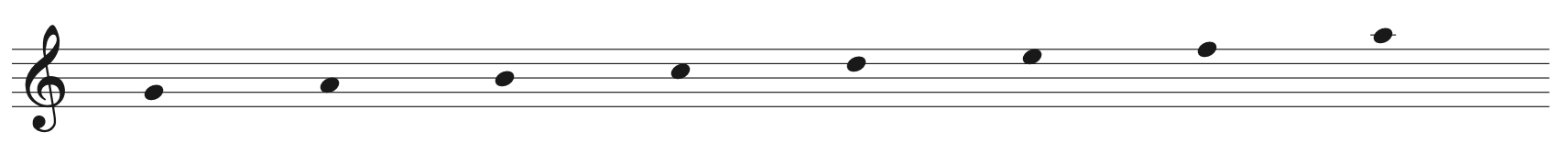

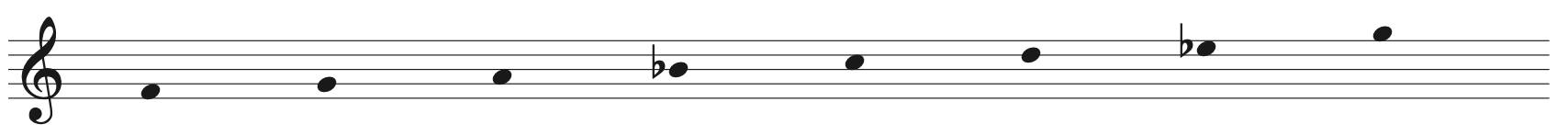

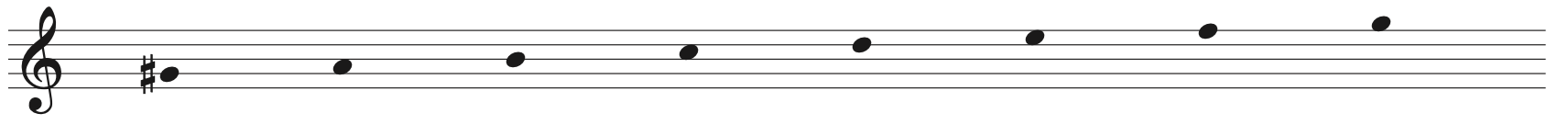

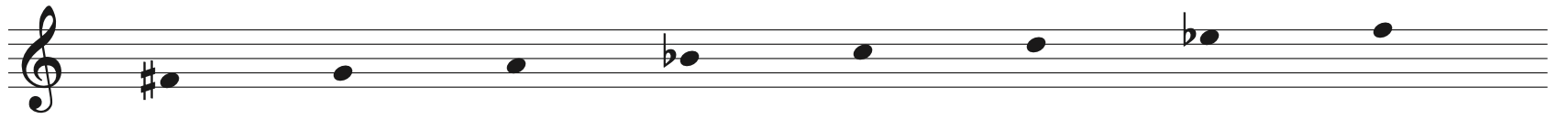

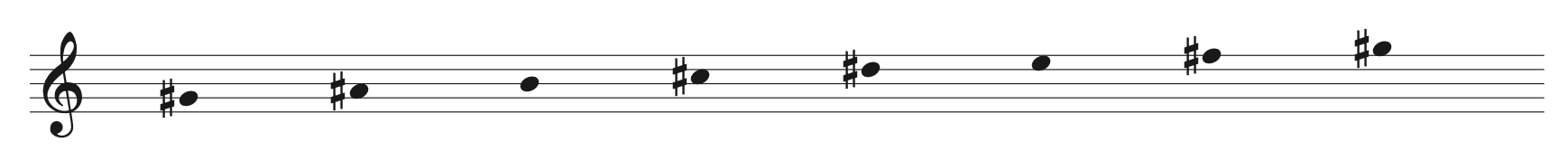

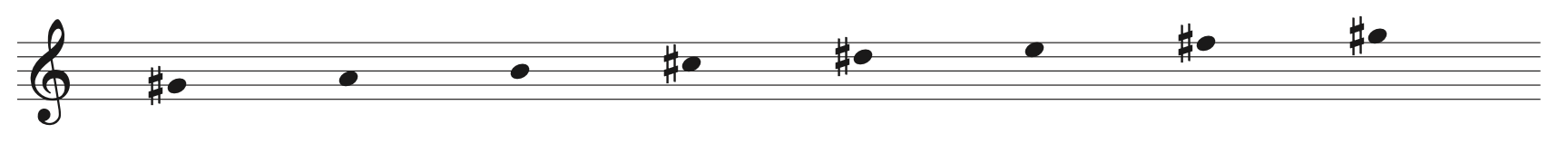

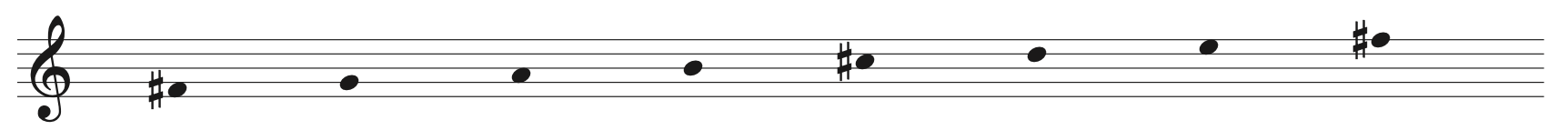

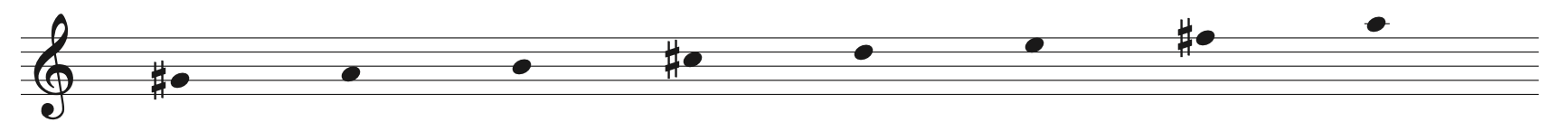

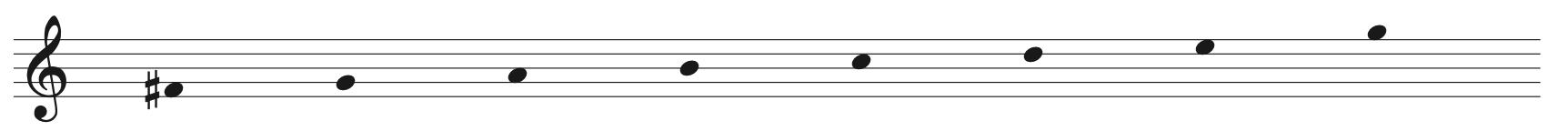

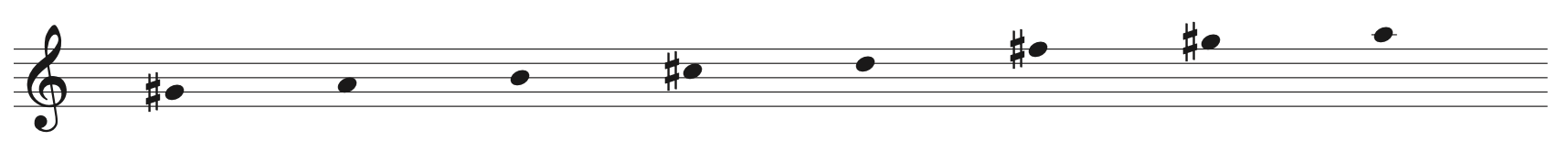

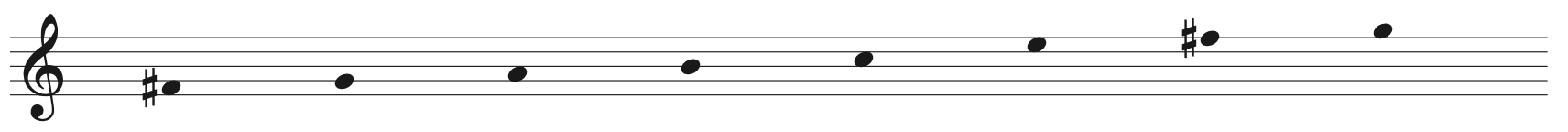

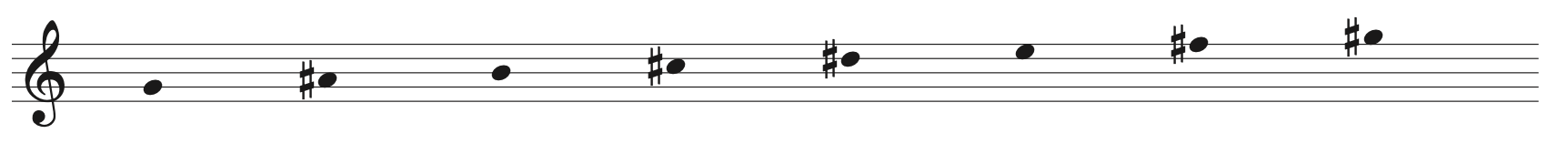

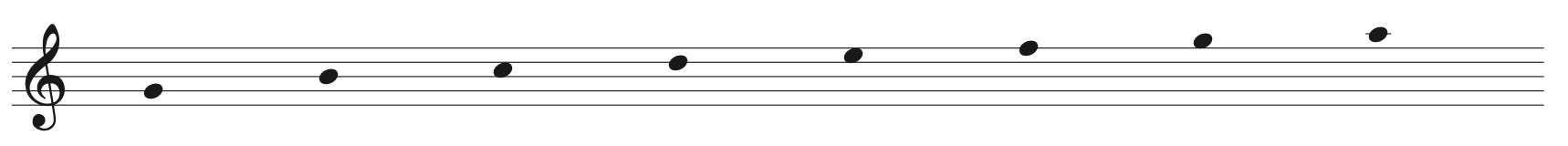

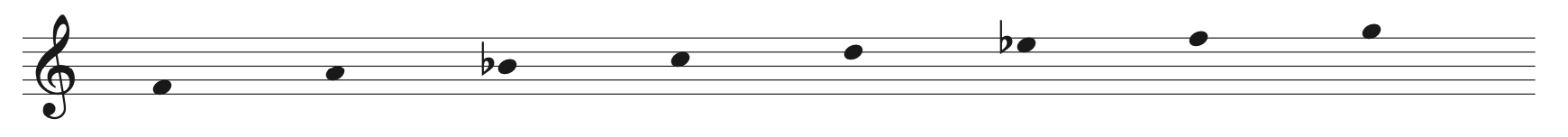

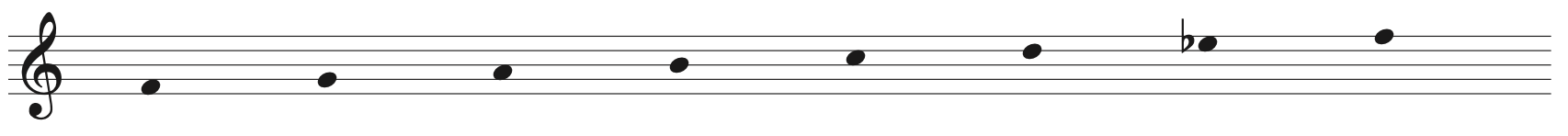

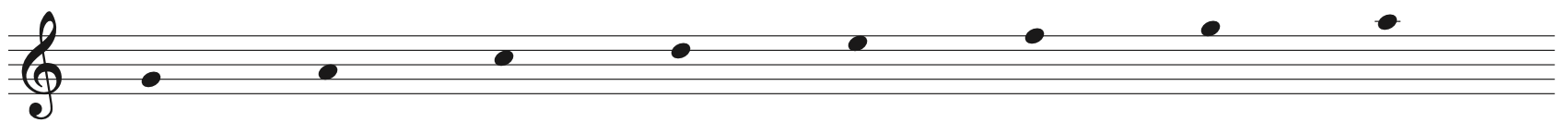

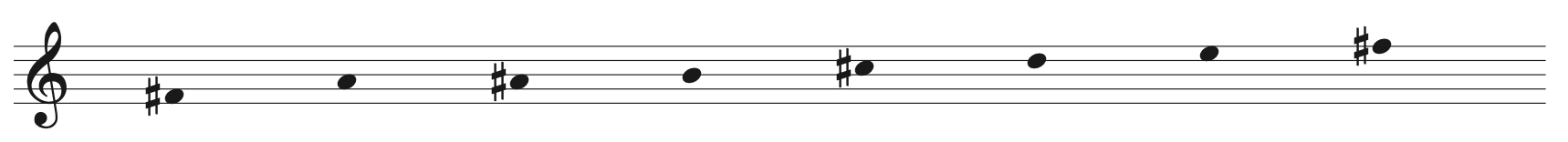

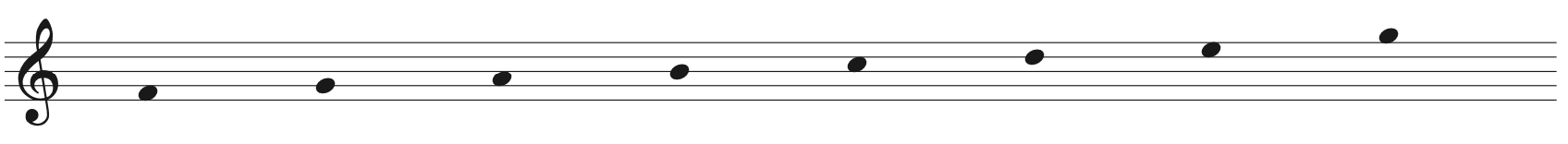

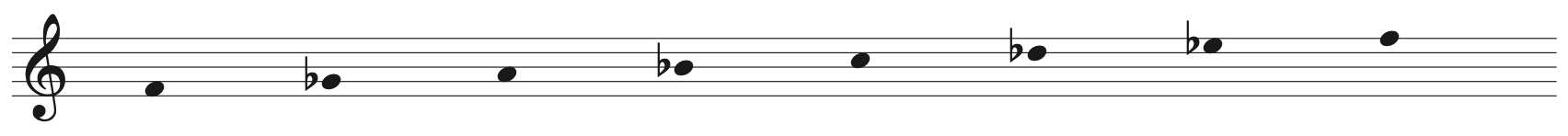

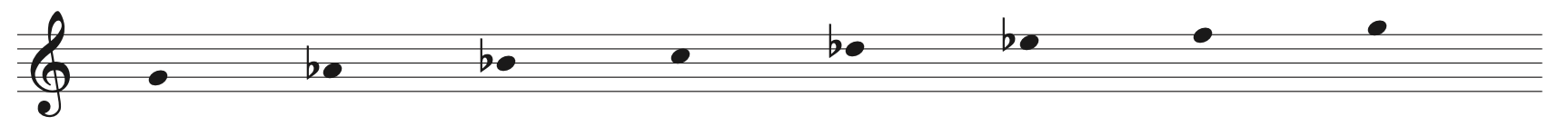

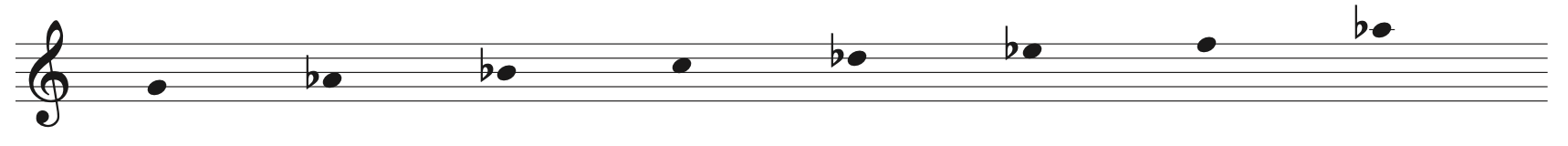

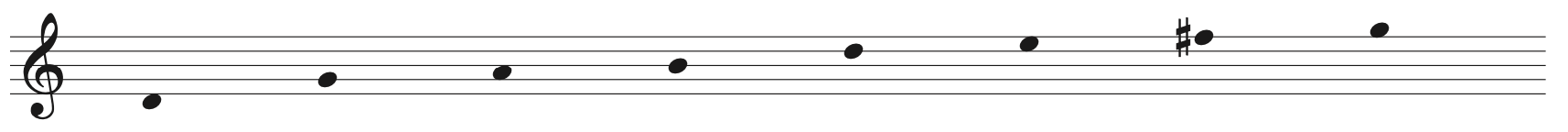

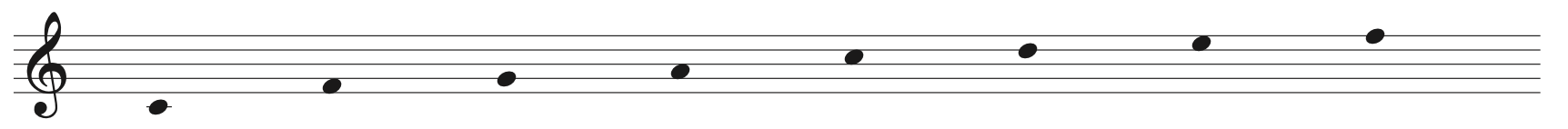

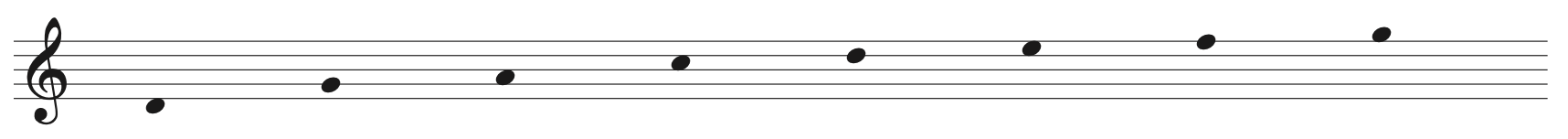

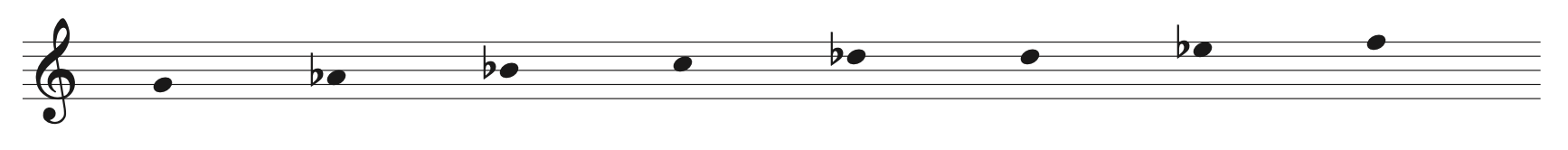

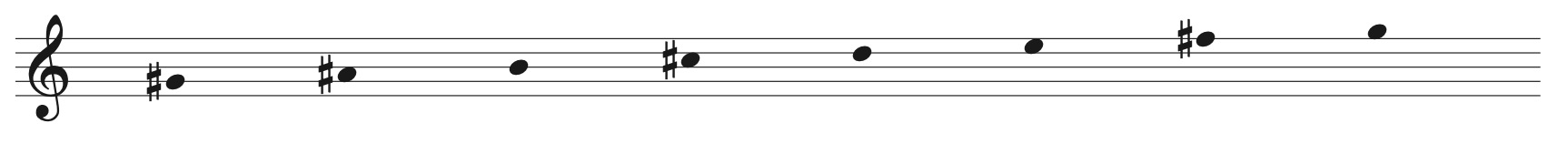

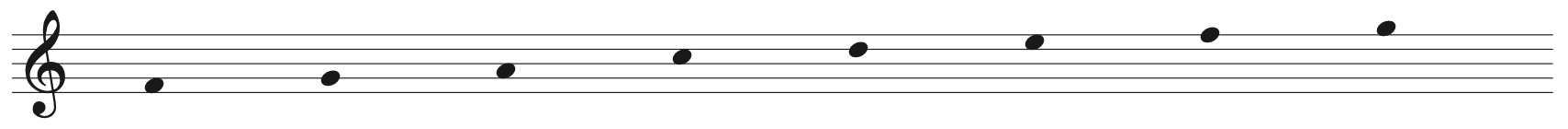

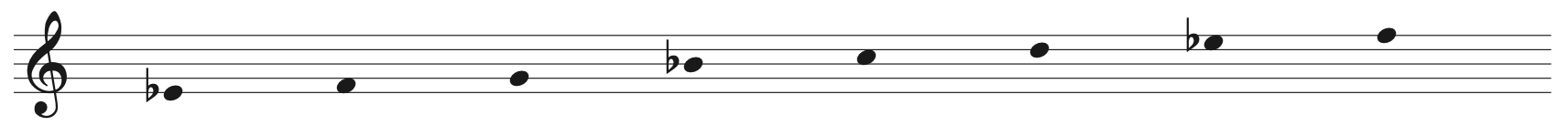

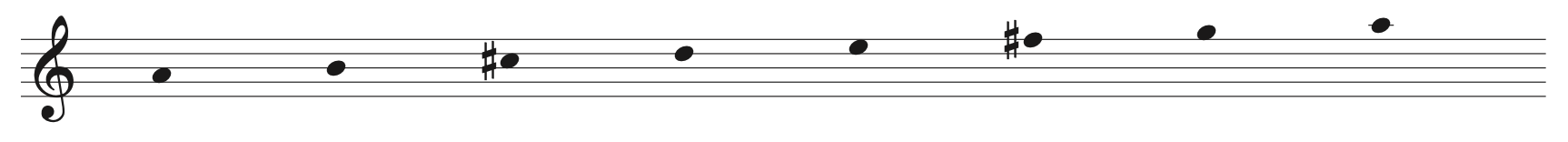

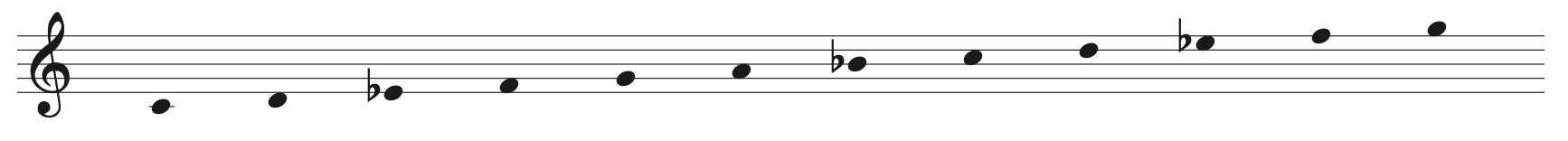

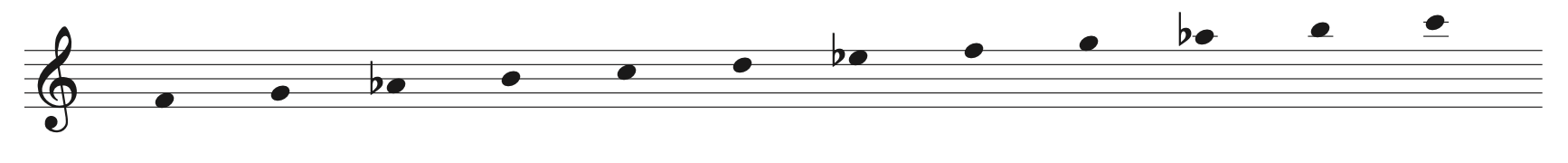

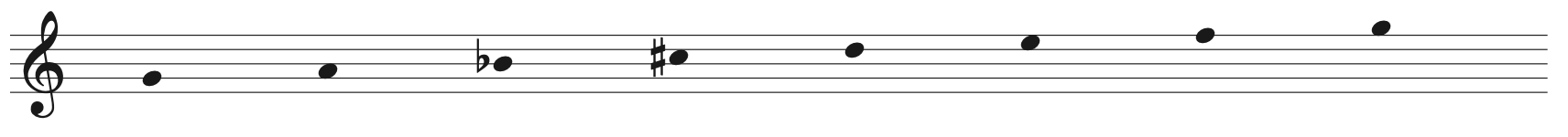

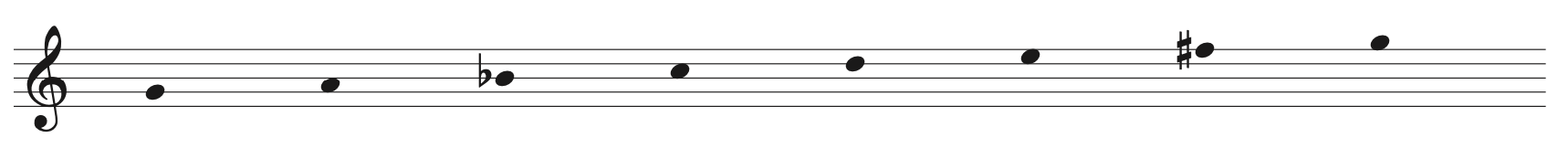

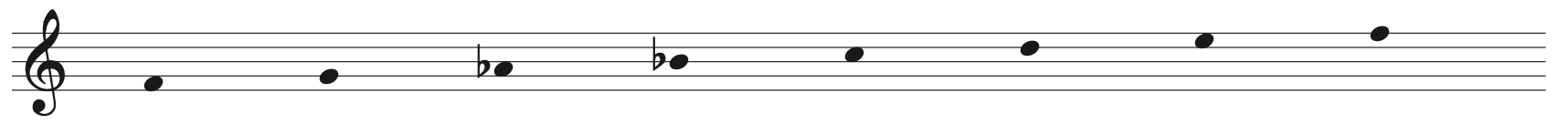

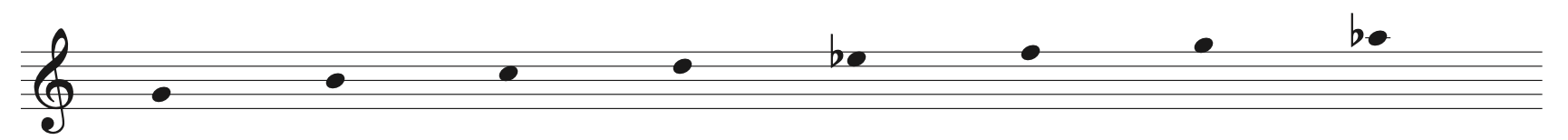

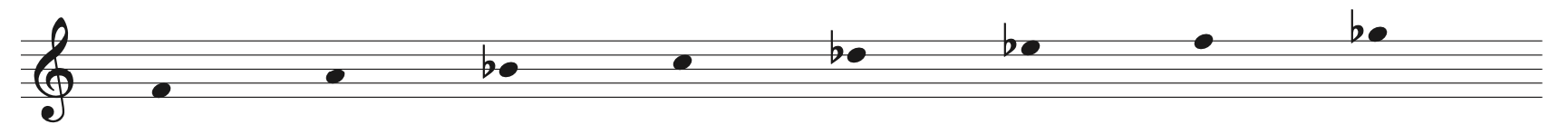

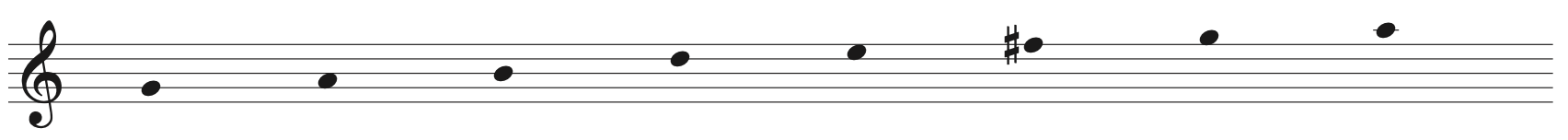

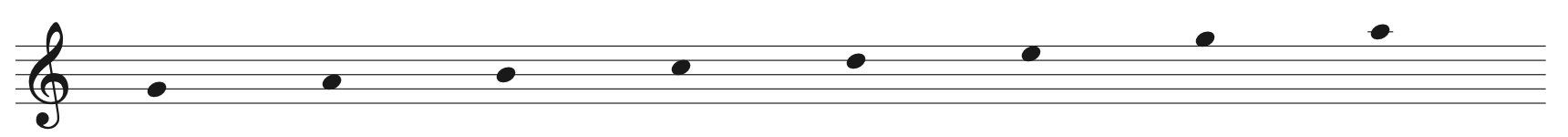

The first aspect of singability is whether the written pitches can be achieved by the singers. Typically, the usual vocal ranges are approximately:

![[Soprano: C-A, Alto: A-E, Tenor: C-G, Bass: F-D]](https://www.choraegus.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/vocalranges.gif)

Please note that I’ve said “approximately” As you may have noticed, I have the unfortunate tendency to violate these estimated range limits quite frequently; part of this is because the Lord has blessed Living Water with singers whose abilities allow me to stretch the pitch envelope appreciably.

Another consideration with respect to pitch range is that of “comfort range”. Most of us have a portion of our range in which we find it most comfortable to sing; this usually is the middle chunk of the pitches we’re able to achieve. It’s important to think about how the vocalists will feel about singing what you write. Once again, this is a rule which I break regularly – unless you interpret this paragraph in a sadistic light – but I’d prefer to think of my understanding of “comfort range” is in view of the talent God has brought us.

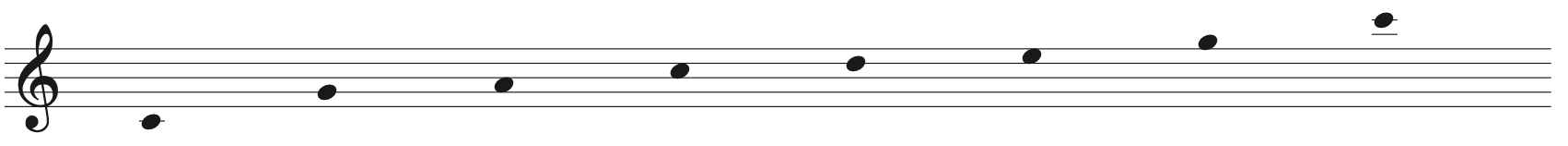

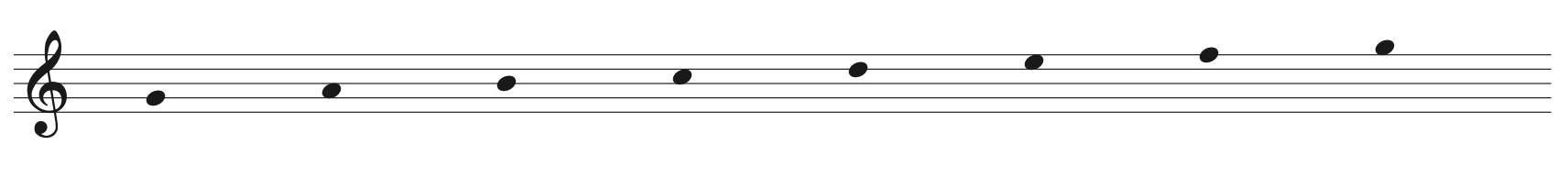

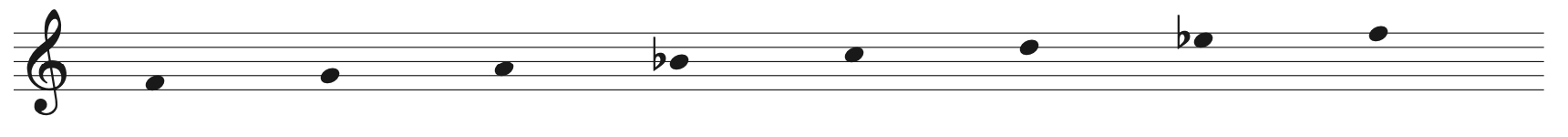

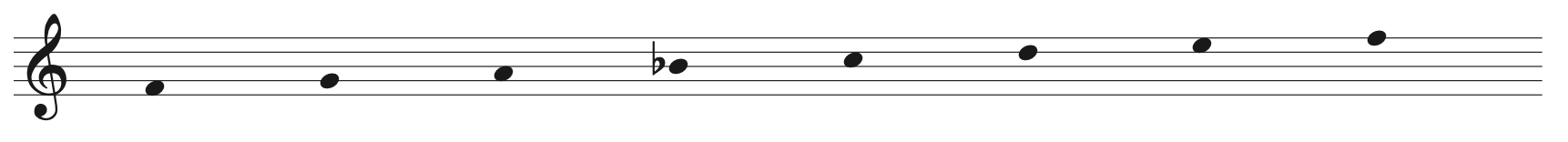

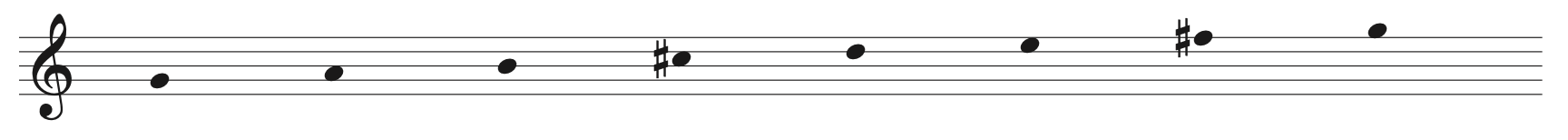

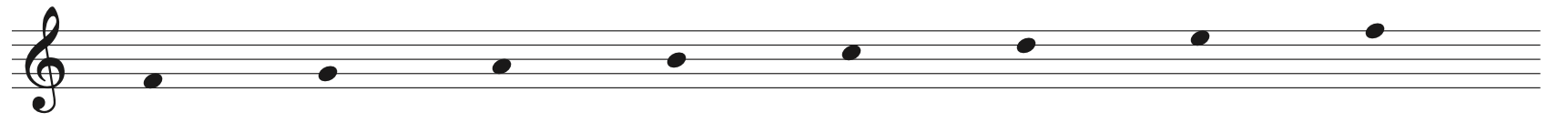

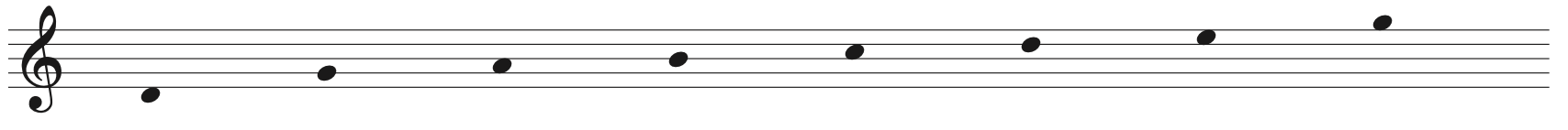

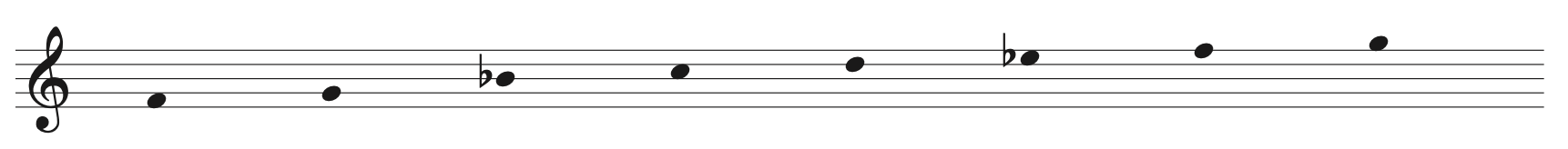

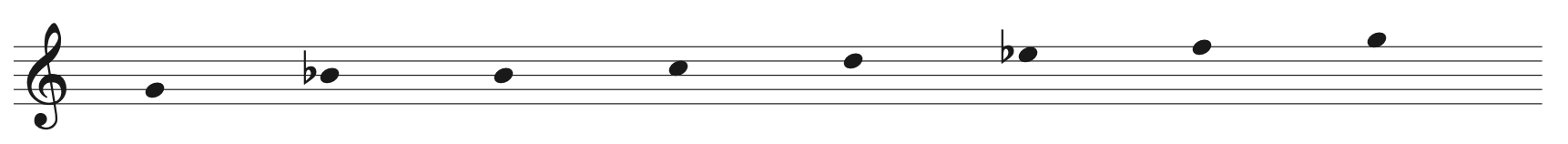

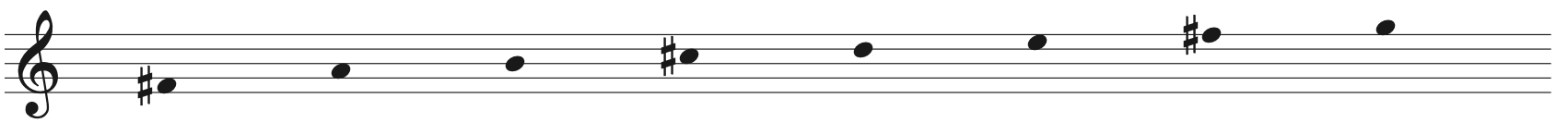

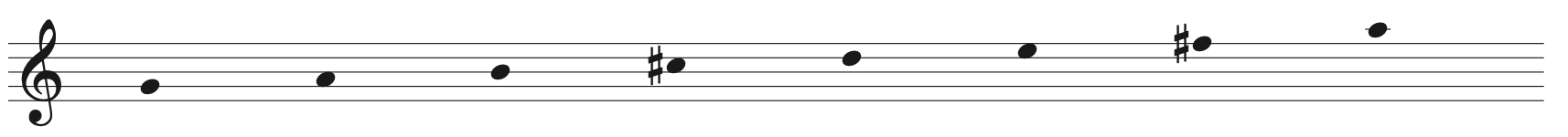

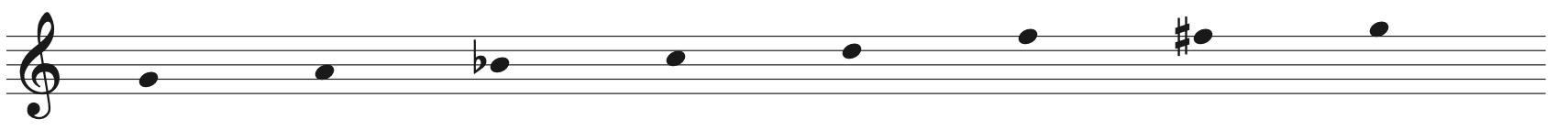

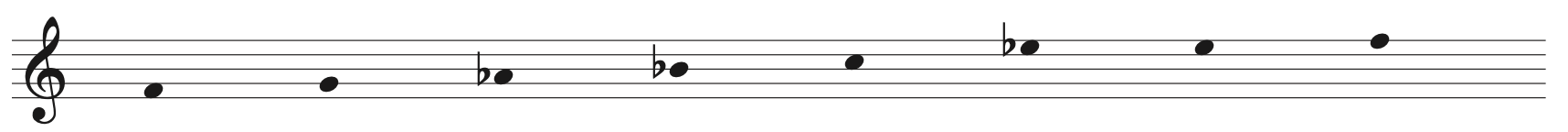

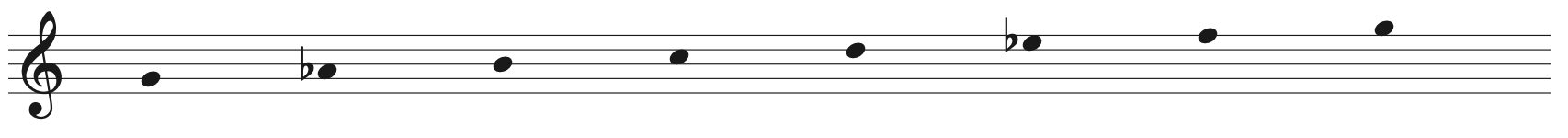

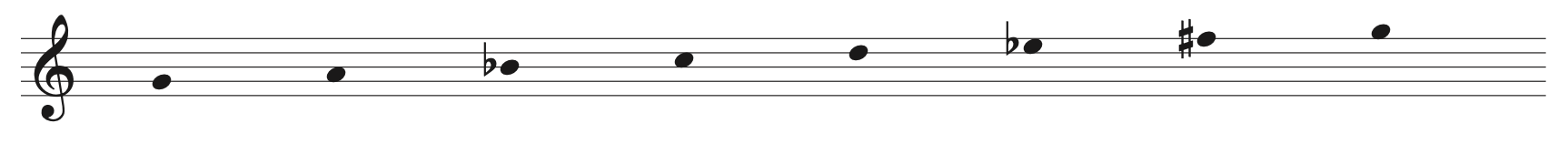

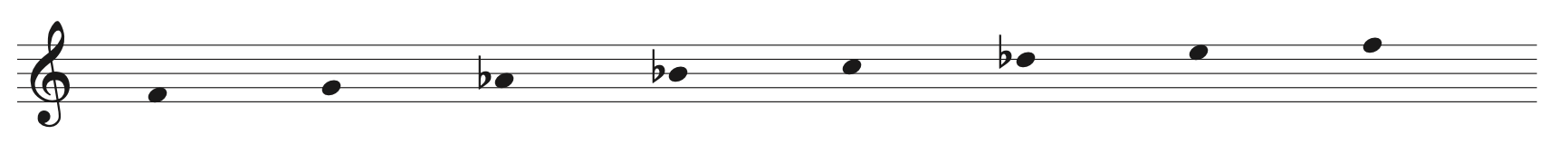

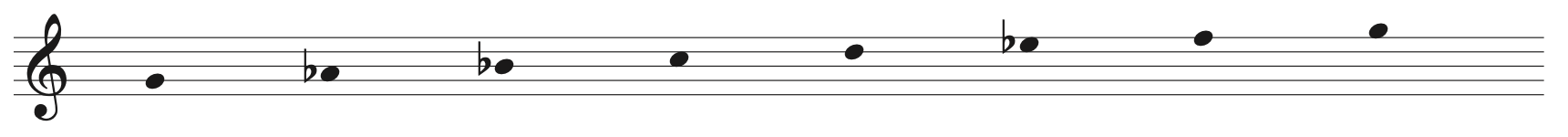

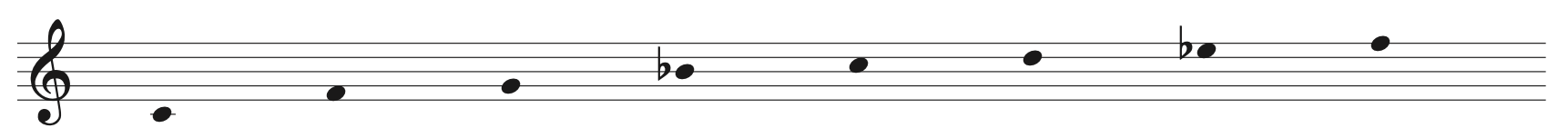

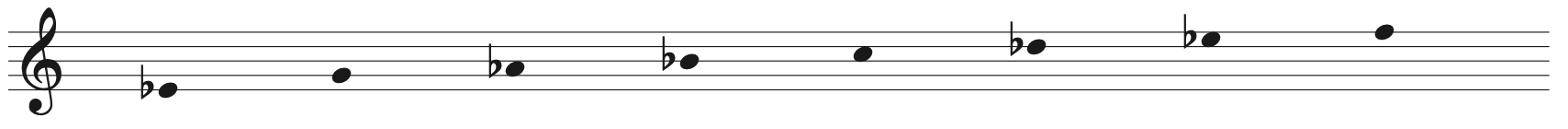

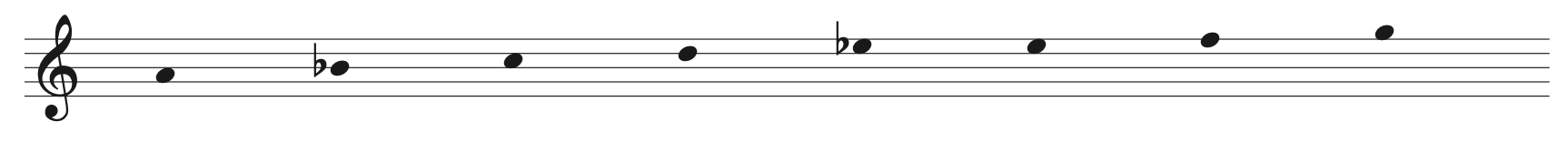

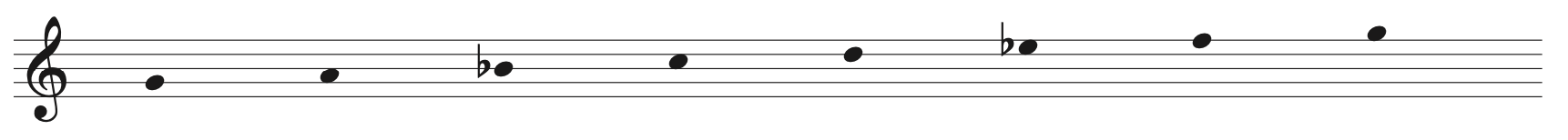

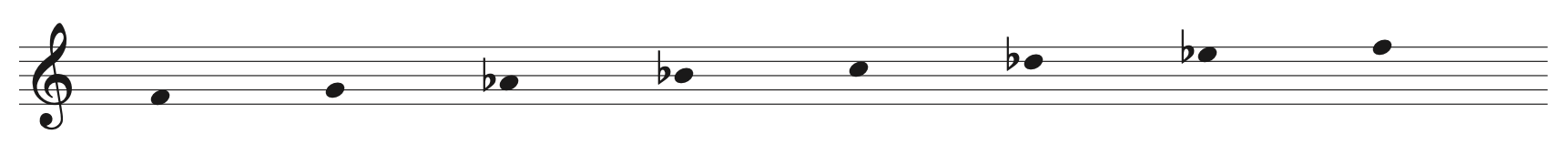

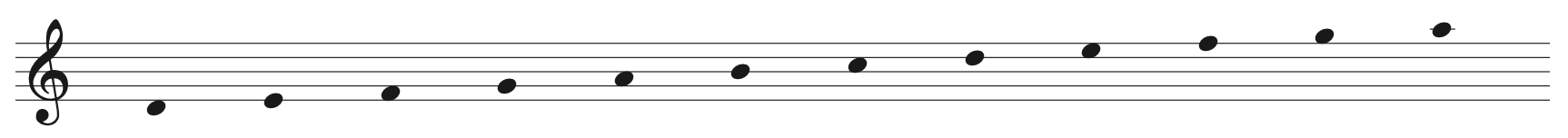

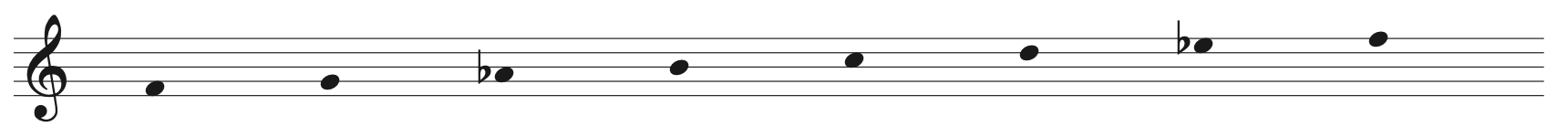

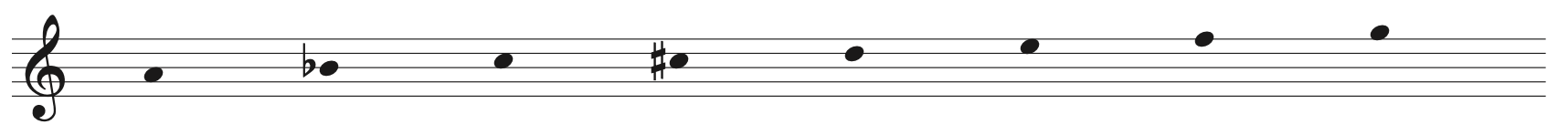

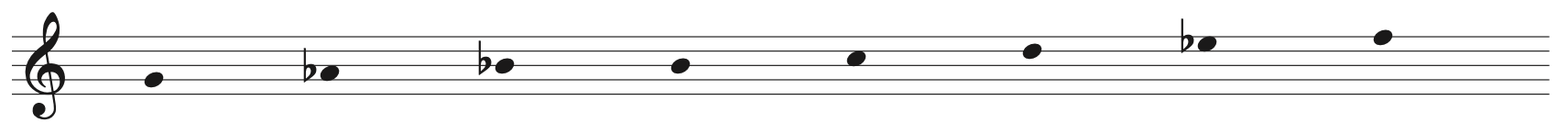

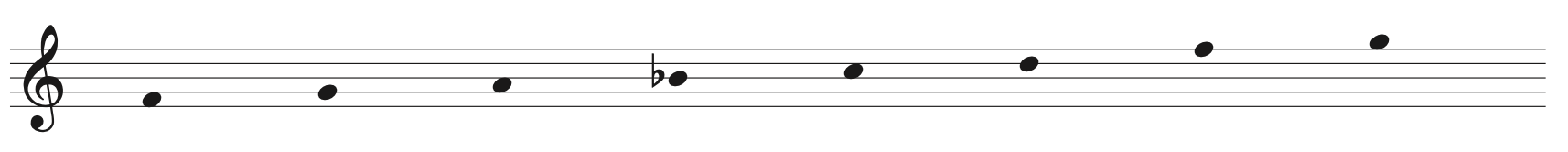

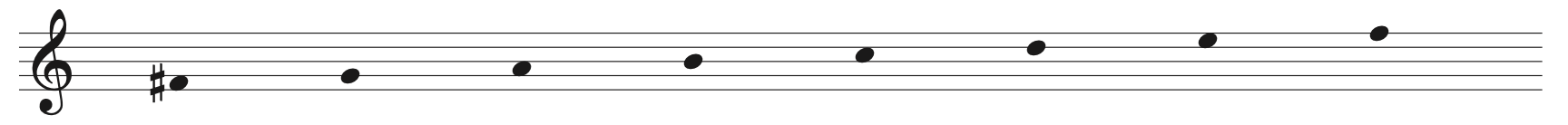

Singability is affected by more than written pitches. The intervals between pitches also play a role in whether a line is singable (as well as enjoyable). Large intervals are physically hard to sing; in fact, they may well jump outside of a singer’s comfort zone. Additionally, having too many large intervals can make a piece unpalatable to the hearer.

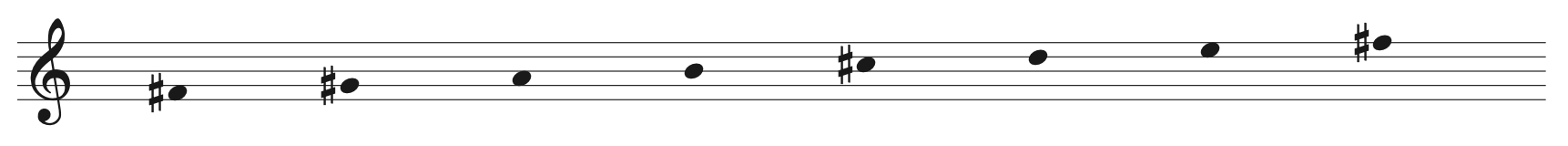

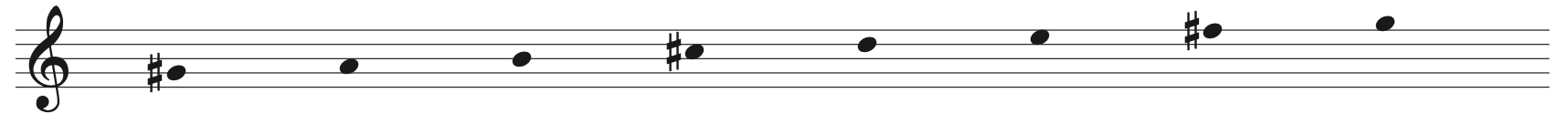

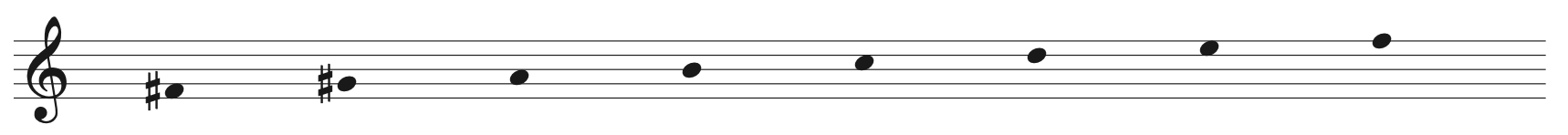

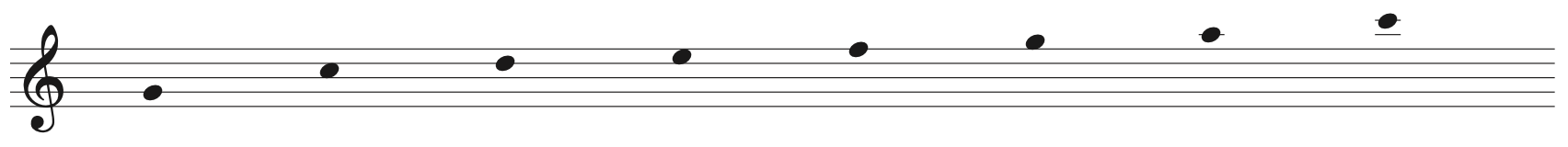

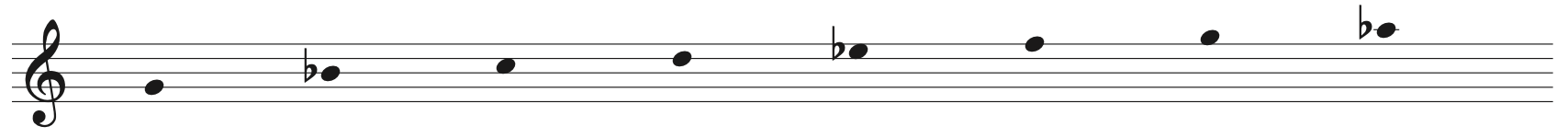

Small intervals are generally easier to sing than large ones (a simple example is a scale). However, having many half-step intervals can also be difficult to sing because of the use of pitches which aren’t in the key signature.

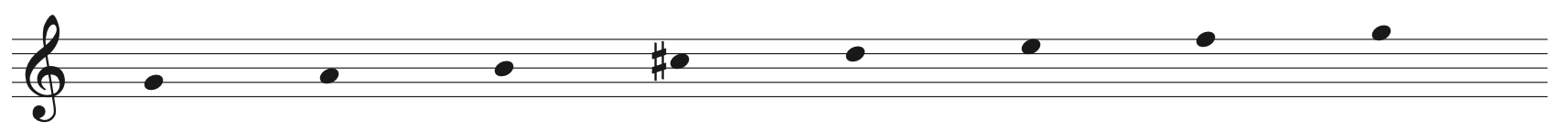

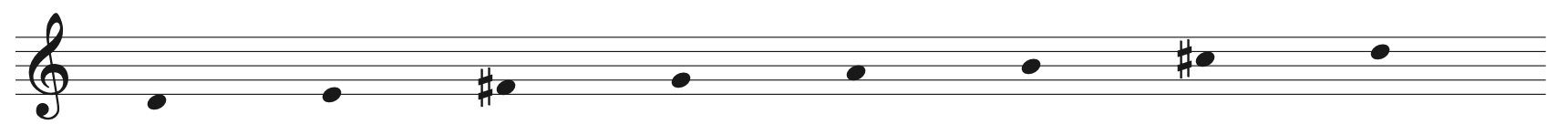

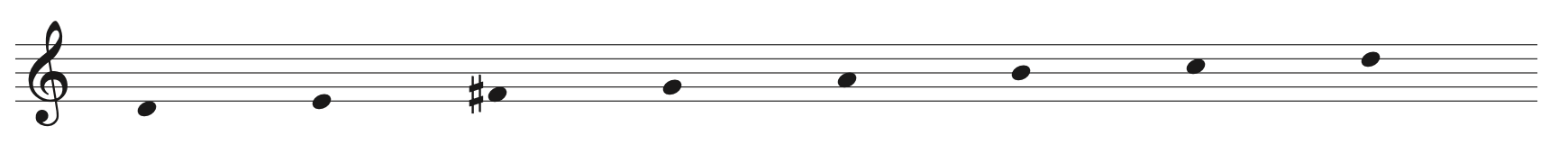

There also are some difficult intervals in the mid-range. The “tritone” (e.g. C to F#) is an example of an interval which is neither small nor large but which tends to be hard to sing accurately.

Finally (for now), modulations – key changes – can make or break a piece, at least from the choir’s point of view. Well-written modulations don’t usually have strange intervals, flow naturally, and can sometimes switch keys almost without you knowing it. Other modulations, some of which I personally am guilty, may have intervals which are hard to feel, much less sing, and may just plain sound weird.

Example: At the Mount Hermon Dimensions in Church Music Conference one year, my roommate and I spent part of Saturday morning running through the octavos in the “bonus packet” (complimentary music from publishers looking to sell stuff…). Most of the pieces were unusable, and then we came across one which appealed to us. Well, it appealed to us until we arrived at the key change, which was so horribly done that we had to stop to roll on the floor in laughter. Yes, tragedies like this do indeed happen!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 6

Our safari into singability continues with a discussion of notes and rests. One special issue is tied closely to syllable count; it’s that of “note speed.” The idea of note speed describes how quickly the individual notes succeed each other in a part. You probably have noticed how difficult it is to sing passages where the notes fly by at harrowing speeds, especially when your choir director is expecting you to sing in such a manner as to make all the words understandable to the audience.

There, however, are musical devices called “melismas,” which are the seemingly interminable runs of sixteenth notes which look like trails of ants crawling on Renaissance and Baroque music (e.g. “For Unto Us A Child Is Born” from Handel’s Messiah). These are interesting in that they have low syllable count combined with high note speed; the emphasis is on the musical line and harmony rather than the text, which is understood at a higher level of abstraction. I’m not saying that melismas are out of date (many composers use them today) – but I am saying that melismas are an element of music which must be watched carefully as to their singability. (Note, however, that melismas are a device which were used primarily in the Renaissance years and the Baroque period when polyphony was the essential driving factor of music. In the Classical period (1750-1810) and succeeding musical periods, polyphonic sophistication of the Baroque ilk almost faded into oblivion. If you’ve studied music, however, you know that big-time polyphony still lives on, albeit in the hack-‘n’-scratch efforts of college music majors who have the “write a fugue” assignment inflicted upon them by their professors.)

The flip side of high note speed is extremely low note speed and long phrases. Both cases will usually require singers to stagger their breathing unless you’re kind enough to tell them in your score when it’s okay to breathe. Also, I imagine that it might be possible to use such a low syllable/note speed that the listener actually loses track of what the words are…

Rests are one of my bigger problems. I never seem to put enough of them in my music! Maybe it stems from my being a pianist, but that really isn’t an excuse since I’m also a singer. Bear in mind as you create your musical lines and harmonies that rests are just as important musically and ministerially as the notes are. A small still voice in the silence following the storm can speak volumes to those who listen!

Another interesting note: there’s room for symbolism in songwriting. Good composers will write music which fits with their words; it seems that the great composers also have a knack for writing music which actually evokes the image of their words by itself. All of this, when put together, adds tremendously to the impact of a song!

Final comment: keep your music singable – but also make it interesting! Pieces which the audience (and even the choir) can figure out completely after half a hearing give the listener an excuse to ignore the music! I’m not necessarily advocating shock effects, but think about it: My feeling about good music is that it keeps the listener “comfortably off balance,” that is, he/she is comfortable listening to it but can be made to lean in the direction in which the music is flowing.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 7

I’ve found that when I write a song, it helps a lot to lay down the framework sometime near the beginning of the creative process. There are a few reasons for doing this:

- It gives me an idea of how much text and music I must write.

- It shows me about how much work I have to do.

- It might provide a clue as to the best musical style for the piece.

There are an infinity of different sectional frameworks which can be worked into a song. Usually, at least by classical music people, they’re indicated by letters. If a section is repeated, then the letter is repeated; if a section is reprised in somewhat altered form, the letter is “primed” (e.g. A and A’). For instance, the “sonata form” is usually called “ABA,” although the pocket dictionary I have at home described it more as “AA’BAA.”

Personally, I’ve changed the letters so that “I” stands for “introduction,” “Vx” for “verse x,” “C” for “chorus” (occasionally “Cx”), “B” for “bridge,” and “T” for “tag/coda.” The value in this for me is that it more clearly defines the music I’m writing in terms of its textual as well as its musical elements. For instance, many contemporary songs use the form “I V1 C V2 C B C’ T,” which translates to “intro-verse 1-chorus-verse 2-chorus-bridge-chorus reprise-tag.”

By the way, I feel that adoption of an unusual sectional form should be justified in terms of the text. My rationale for thinking in this way is that an unusual section form has a tendency to leave the listener a bit lost because of its unfamiliarity; consequently, the text must provide a logistical anchor for the audience to appreciate the song. A very good example of this is Dave Ruder’s “Rejoice In The Lord” (really tough to sing, but a dandy piece based on Philippians 4:4-9 – if you want to look at it, you’ll find it in box 266 in the Valley Church choir library). Dave wrote this piece based on the text, which happens not to rhyme, which happens not to have any strong metrical patterns, and which happens to display several different moods in only five verses. So Dave wrote the piece as an a cappella motet, a musical form which essentially is a chain of different themes tied together by the continuity provided by the text. To package the piece neatly, the first theme is reprised at the end, so the musical form is “ABCDEA'” (you might happen to remember when the Sanctuary Choir sang this about three years ago).

One final word about music (and text): If you decide to use someone else’s music or words, you are required by the U.S. copyright law to get the copyright holder’s permission before you use it. You can ask by writing the publisher or composer, detailing why you want to use it, what sort of arrangement you plan to do, where and how you’ll use that arrangement, and how many copies you intend to make. Bear in mind that if you don’t ask and tromp on someone else’s legitimate royalties, they can take you to court to recover said royalties…

Many copyright holders will return word that it’s fine for you to use their stuff for free. However, there are some who will tell you equally kindly that permission is not granted (usually for reasons best known to themselves). The largest number of responses, though will come from those copyright holders (mostly publishers) who will send a relatively informal contract stating the purpose, number of copies, and quoting a nominal price (e.g. 50¢) for each copy you intend to make, and further stating that you agree to use the arrangement for personal use only, i.e. not for profit. Benson, among others, might also require you to send them a copy of the finished product so that they can evaluate it for publication.

Of course, this is all a moot point if the piece or text you wish to use has reached “”public domain” status. If this is the case, it means that the copyright has expired and that anyone can use the piece, whether for profit or not. Many of the old hymns fall into this category; virtually all of classical music, at least up to the last century, also is public domain. To check whether a piece is public domain, you can check the copyright index in a hymnal or contact the publisher if the piece was first published in the last eighty or ninety years (notable exception: a couple of Scott Joplin’s original pieces are still in the hands of their copyright holders and remain unpublished as of this writing).

Final note: The current copyright law (which you can get from the Information and Publications Section, LM-455, Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559) states that a copyright expires fifty years after the death of the last applicant listed on the copyright form. “Out of print” does not mean that the copyright has expired! However, copyright holders are usually quite generous in that they’ll let you copy out-of-print stuff for free (or at least for a nominal fee), and in whatever quantity you specify.

Why all this about copyrights? Read Romans 13!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 8

Part of the essence of a song is the style in which it’s written. Different style evoke different reactions. For instance, you’d get a severely different reaction if you did Bill Gaither’s “He Touched Me” in the original gentle style than if you did it in heavy metal mode (that would also be a violation of copyright law without obtaining approval…). You’d offend more people with the latter, among other things.

The core concept here is that a song is a marriage of text and music. It doesn’t mean that the words and music have to be created at the same time; sometimes a new song is created by taking a preexisting text and setting it to music (witness all the anthems based on the Psalms), or by writing text for/matching text with an existing theme (“Be Still My Soul,” arranged by Dan Bird based on a melody by Sibelius, is good example).

This marriage must be a fully functional rather than a coincident one. You can draw a parallel to the way most seasoned marriages work, especially with the added dimension of having children. We don’t do everything in lockstep; however, we aren’t completely separated from each other. There’s some overlap, and there’s some freedom on both sides (I can go bowling; she can go to school and earn a third master’s degree is she wants).

I’m not trying to say that the music and text shouldn’t match; they should! But they don’t have to be slaves to each other, and while they express the same thought, each should do it in its own particular way, leading to a unified expression of truth. This sounds a lot like how the Church ought to function as the Body of Christ!

There’s a pragmatic side to style. If you’re writing music which is intended to minister, you must account for the tastes and sensibilities of the congregation for whom the song will be sung. That doesn’t mean that you have to be so middle-of-the-road that you end up writing in a colorless style, but it does mean that you have to maintain an awareness of where the acceptable “style envelope” is. I’ve appreciated the congregation at Valley Church very, very much for their appreciation/tolerance of an exceptionally wide array of musical styles – over the last four years, the Valley family has heard songs in Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and even a touch of Contemporary classical styles, as well as pop, swing, jazz, Big Band, (mild) rock, country-western, Broadway, and rhythm-‘n’-blues and they’ve all been appreciated! Well, okay, the first time the quartet sang “Have You Made Your Reservation” (from the Gaither Vocal Band repertoire), some people raised the quizzical eyebrow when Dennis Mays started up the “Amen”‘s and “preach it”‘s in second service, but in general everything has gone over well.

Further, I’ve also appreciated the openness that there’s been for new compositions. Even though it can be difficult to write new music, having a receptive audience for it and the musical wherewithal to perform it – Valley is blessed with tremendous musical resources – is a huge plus which must not be overlooked.The result is that we can write and sing in almost any style, knowing that it will minister to the people who hear us.

Example: A couple of years ago, I wrote a song which I showed to Tom Shedd. He asked if we could use it for the Easter service at Flint Center (“Of course!”) – and then followed up by asking if I’d ever written an orchestration before. In spite of never having done that, I agreed to put something together – bear in mind that this was two weeks before Easter! – and worked like mad to put it together and to write out all the parts. Thanks to God providing the strength and creativity required, the parts were ready by the Saturday rehearsal, and we ran through it a couple of times. It sounded great on Sunday morning (so I was told; the Sinfonia was so large that day that I had to direct them from the dead spot which is just in front of the first row of seats) – Tom did a marvelous job on some very difficult lyrics, and what I could hear of the parts balanced very well. Pastor Steele even made a point of telling the people at evening service about the song – PTL!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 9

“Variety is the spice of life.” This is especially true with respect to songwriting because of the need to retain the audience’s interest, and it’s even more important in Christian music because of the potential impact of the message of salvation.

There are two sides to this issue. The first is that most people won’t listen to music in just one style. The other is that for each person there are style which are relatively unpalatable. I can listen to [i.e. tolerate] one or two country-western songs in a row, but I’ll change the station if the third one starts immediately after that; this isn’t one of my favorite musical styles (curiously, “Flying Home” is written in this style…). On the other hand, I can enjoy jazz/fusion jazz for an almost indefinite period of time, and can leave my radio at that place on the dial – that is, at least until the DJ decides to play a style which I don’t prefer. Bear in mind, however, that I’m not trying to discredit any particular musical styles: I’m just saying that they’re not on my personal preference list.

I suspect that most of you are this way. If you scan your tape/CD collection, you’ll probably find a variety of styles. Your own taste in music (or anything else) usually moves you to explore more than one aspect of the field because it’s interesting, and, even more importantly, fun.

When we apply this to songwriting, it means that we need to experiment to develop new ways of communicating our message. You can look at this in the past tense and in the future tense – the present tense is the here and now in which you’re writing your music; it’s work in progress.

The past tense consists of looking back to pieces you’ve already finished for the purpose of determining what worked and what didn’t. By this I mean that there may have been some aspects of a previous composition which had a favorable impact on the audience, and that there also may have been some which didn’t.

An example is Alison’s song, “Walk Beside Me.” Personally, I think that the baritone horn solo worked extremely well under Mike Lyon’s expertise. The vocals and piano also meshed together very nicely, and when they were combined with the baritone countermelody at the end, the effect was wonderful. I wouldn’t mind writing another song with that sort of arranging, perhaps three or four years in the future.

There, however, were a couple of things which I felt didn’t work all that well. A couple of lyric lines sounded a little strange (for instance, “Hello, my friend, how are you?”). The conversational approach was more curious than effective, or so I thought, and I don’t know if I’ll try it again.

A special case was the word transient.” I admit to having a fairly strong vocabulary, and the word just poured its way out of my pen as I was working on the text to this song. However, it turned out that a lot of people in the choir didn’t know what it meant, much less how to pronounce it. I suppose I was walking the fine separating comprehension and misunderstanding on this one. Consequently, I probably will be trying to make my song texts more understandable. But understand this: I believe that, as a songwriter, it’s my responsibility to educate and to challenge the listener to some degree; I just don’t know what degree that is.

Overall, though, “Walk Beside Me” went over very, very well. I heard lots and lots of very positive comments about it. Someone even told one of the choir members that we should sing the song again in the future! So, in spite of the few things that bothered me, I guess the Lord used this song as a very nice ministry tool.

As you write your music, I’d suggest that you deliberately try to infuse variety into what you compose. Play around with all of the aspects of the piece:

- Voicing: Rather than write only SATB music, try SSA, TTBB, SSAATTBB, SSATB, SA, or unison. It seems to be much more difficult to write pieces which sound good with fewer vocal parts!

- Style: Explore a sampling of styles. Within the Valley Church context, we’ve been able to minister with Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, Romantic, ballad, R&B;, 50’s rock, 80’s pop, calypso, and other styles. Perhaps even reggae or jazz would work too!

- Accompaniment: Most church music accompaniments are written for piano or organ. While it’s possible to do quite a number of things with keyboards alone, adding other instruments (readily accessible via electronic keyboards!) can really make a piece work well too. I’ve had a lot of fun writing parts for baritone, cello, and trumpet, among other instruments.

Once you get rolling and have written a few pieces, it’s important to take a retrospective look now and then. You should do this to detect your compositional tendencies – for the purpose of breaking patterns! Check for habits / personality traits in your lyrics, your melodies, and your harmonies, as well as your voicings (how the vocals are arranged) and your accompaniments. Dave Ruder (Annette’s dad) has told me more than once about how much he dreads looking through music by certain composers because they almost always use the same compositional devices (try eating the same chicken recipe three times a day for a couple of months and you’ll see what I mean). You can decrease others’ appreciation of your work by doing this to them; these particular composers are cases in point.

I find that my lyrics include words such as “forever,” “all,” and “every” fairly frequently. I’ve also found that I like to start melodies on the third tone of the scale (E in C major), and that I like bass lines which walk down the scale. Being a pianist, I tend to put fewer rests than I should in my music; and because I seem to have too much to say at times, my lyrics lean toward the long/complex side.

Having observed these compositional idiosyncrasies, I’ve tried to write music which changes one or more aspects. I recommend the same for you if you get into composing enough to detect your own predilections. Bear in mind, though, that this occasionally becomes a rather schizophrenic experience because, after all, you’ll be composing effectively by trying to change your personality. I suspect that doing this can teach you a lot about yourself!

One more thing: Be aware of where the “appreciation envelope” is in terms of your audience. The purpose of writing music is to glorify God, and in order to do that the congregation listening to your songs has to appreciate or, as a minimum, tolerate the songs they hear. It’s okay to “push the edge” once in awhile, but incessant envelope-stretching tends to be hard on your effectiveness as a minister in Christ’s church. Keep the goal of ministry in mind even as you build the tools used in that ministry!

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 10

Here are a few other ideas which might help your progress on the path to effective composing. Depending on your experience and training, they may or may not apply, but of course you can just skip those paragraphs if you’re so inclined (it’s not as if I can make you read them…).

- Expand your vocal skills. Learn new styles and how to sing them, master the sounds, tones, and diction of those styles so that you can write in them. Some of you might even want to take this as far as investing in voice lessons or joining a band somewhere!

- Develop your instrumental skills. Piano/keyboard experience is perhaps the most useful instrumental skill in composition because it captures all the pitches you’d want (or be able) to sing, as well as providing a facility for playing more than one note at a time. I find that if I think in terms of a single instrument (e.g. clarinet), I start to forget that there’s more in the world, and the words, vocals, and accompaniment suffer accordingly.Incidentally, learning instruments other than piano is much less critical an issue today because of the electronic keyboard. You can buy keyboards which have all the instruments you can imagine, as well as capabilities for creating instruments that no one’s ever heard before. My Korg M1 also has multitrack playback capability and combination patches, which enable me to hear more than one instrument simultaneously. However, I might add that it’s a good idea to learn the sounds on each instrument (can you hear an French horn in your mind?) so that you’ll have a better idea of which keyboard patch to select before you start doodling.

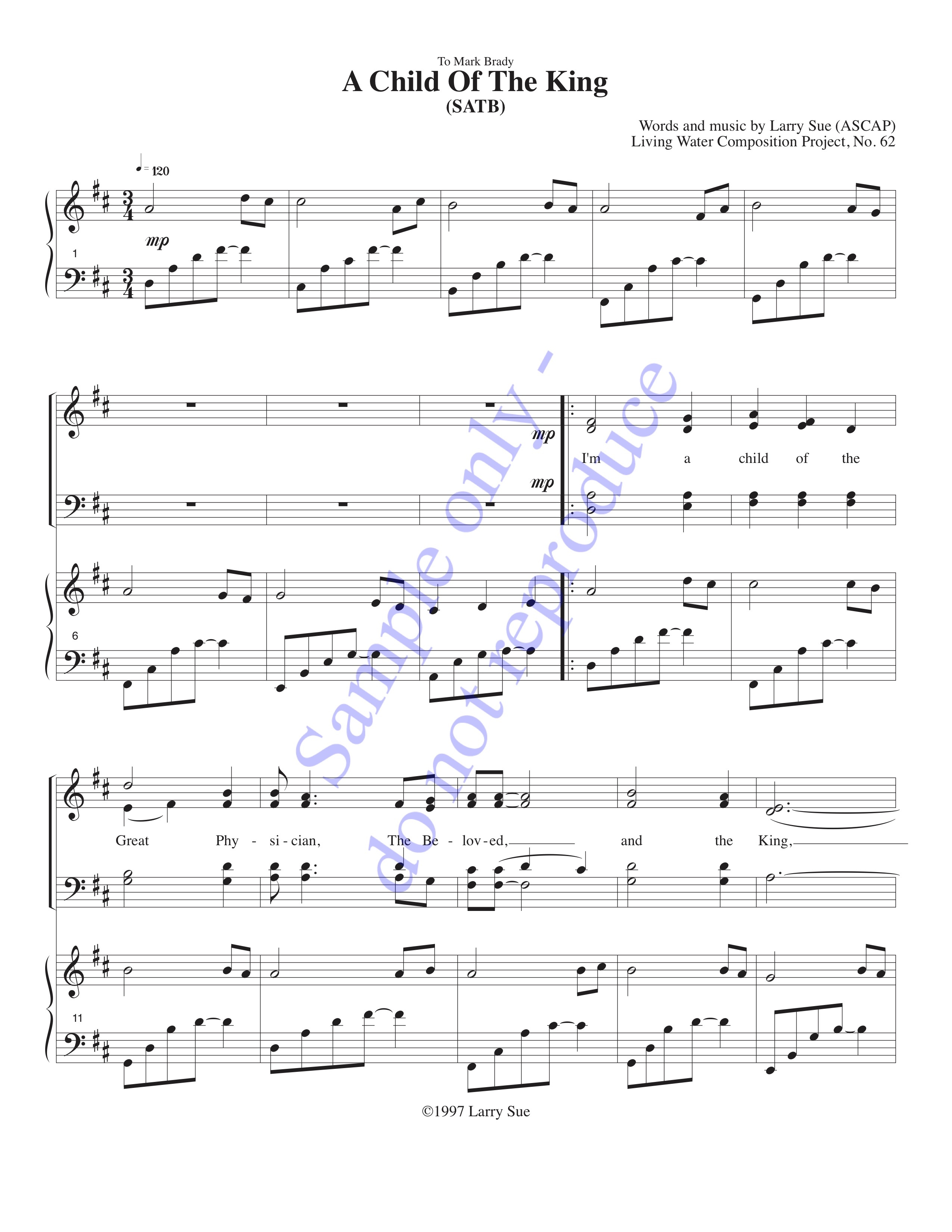

- Study music written by a variety of composers (in fact, study the composers too). This can give you insight into musical style and perhaps provide ideas for an approach to a composition. For instance, I borrowed heavily from Mendelssohn’s and Brahms’ styles when I worked on “He That Dwelleth In The Secret Place Of God.” The result was a piece which I personally enjoy hearing and which I’m looking forward to directing, as well as my acquiring an approach to writing more pieces in this style if I feel so inclined.In addition, you might find a way to share ideas with other composers (Valley Church is blessed with a number of such people). This might also provide a shortcut to achieving the composition understanding which I described in the last paragraph. But at the very least, you’ll get some much-needed encouragement when you need it, and perhaps insight into breaking any mental impasse you might have encountered.

- Go to reading sessions and music conferences. Reading sessions can be relatively inexpensive (five or ten dollars), and they’re a lot of fun to attend. You get to meet a lot of fellow choir people, many of whom are directors and some of whom are composers, and you get the benefit of the clinician’s expertise as you sing. Some of the Sanctuary Choir members went to a one-day choral festival a few years ago and spent the day learning from Dan Bird, who’s the Minister of Music at Lake Avenue Congregational Church in Pasadena (with their 4500-seat sanctuary and 300-voice choir…). We prepared seven or eight pieces and sang them that evening – it was wonderful!Music conferences tend to be a good deal more costly than reading sessions because they’re longer and more intense. I’ve been going to the Mount Hermon Dimensions in Church Music conference for the last five years and have always had a great time there. It’s a week of reading sessions, workshops, and panel discussions mixed with terrific fellowship and a lot of fun. We spend a good part of the week preparing for a Saturday concert which includes the conference choir, the orchestra, the handbell choirs, and other things, such as a solo by the organ clinician (Bob Plimpton, the San Diego Civic Organist, played a piece entitled “Pedal Variations” for us – and also added a little bravado by playing it with his hands in the air in much the same way some people ride a roller coaster – it was marvelous!). I’m still hoping that some of you will join me there one year; the cost is rather high, but I think it’s worth it.

Next time: Thoughts about getting your music published.

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 11

Writing music is a great thrill, especially when you hear it sung in church and people praise God because of it. This, I believe, is where the true rewards of giving your compositional abilities to God come into being. The Lord has given me great blessings because He’s been able to use me in this capacity.

But there also is a wider field available. Having your music published is a steppingstone to a broader ministry for the Lord because it effectively increases the size of the audience. The privilege of having a publisher accept a piece for publication is a tremendous (and rare) one. Let’s take a closer look.

You’ve written a song which you’ve performed at church and everyone’s told you how wonderful they thought it was. You even still like hearing the piece after beating your brains out on writing it for six months, and would like to share it with more people. After all, it’s a hot piece in the mold of the songs you’ve heard on your albums!

So you pop it in a envelope and mail it to [Publisher_1]. The envelope returns, unopened, with nothing said by [Publisher_1] except “return to sender.” So you try again, and send it to [Publisher_2]. They return it, saying that it “doesn’t fit their publishing needs at this time.” One more try: you send it to [Publisher_3]. They return it too, saying that they are “currently not accepting unsolicited material.” And then you try [Publisher_4], which replies with “we do not have room in our publishing schedule for your piece,” and further ask you to send $1.67 to cover return postage.

This is pretty much what happened to me when I started sending my music around for publication consideration. It was very frustrating because I thought my stuff was a lot better than these people appeared to be saying it was. I wanted to minister in a wider arena (and royalties wouldn’t be so bad either…)!

Some of why all this was happening was explained by Fred Bock in a workshop he led at the 1990 Mount Hermon conference. Fred’s a publisher as well as a minister of music, and so he has a unique view of the Christian music world; as far as he knows, no one else has a foothold in both worlds.

Fred’s basic premise was that music publishers have to make money. If they don’t, they file for bankruptcy under Chapter 11. This means that they have to publish music which will earn a profit, and also means that they have to weigh the financial risks of each piece as they decide whether they’ll accept it; a publisher must pay the money to edit, typeset, and print a piece before he even sells the first copy, which is an investment of thousands of dollars.

There also are limits as to how many pieces a publisher can accept; Fred tells me that he issues only about fifty new pieces per year. This means that if Fred receives a hundred good, publishable pieces in a given year, half of the composers involved have to be turned down. He just can’t accept them all, and it must be a really tough decision for him when this happens. By the way, an established composer (e.g. Dick Tunney) has a much better chance than you or I do because his name has a fair degree of selling power. That’s why some people appear on the music shelves at the store so often.

[Christian] music publishers also must preserve their doctrinal perceptions. Most are pretty agreed on music that they’ll accept, at least doctrinally, but they probably have a tendency to play the game close to the middle of the road so that they don’t offend potential customers (remember the first premise!). This, however, doesn’t means that they’ll publish all good music, and it further doesn’t guarantee that they won’t publish bad music.

Overall, though, you can trust them to accept your songs if they’re doctrinally sound. It’s the left-field points of view which make them itchy. I’m not saying that you should milquetoast your message, though! You can take a hard stance in your lyrics as long as the message is presented considerately.

Back to the rejection letters: Fred made it very clear that publishers, in addition to having limitations on how much music they accept, don’t want to get into fights with those who submit songs for consideration. In the above example, [Publisher_1] returns music unopened because they don’t want to be accused of stealing other people’s ideas. So they just play it safe and return mail everything which is unsolicited.

Suppose [Publisher_2] is a denominational publishing house which concentrates on more conservative forms of musical expression. Consequently, rap and metal groups aren’t going to gain much of an entrèe with them. My song apparently was not in their style. This is important, because a publishing house usually has to refine its customer base from “everyone and his brother” to something smaller, such as “people who like conservative musical styles,” “teenagers,” or “people with no hearing because they always turn up their car stereos high enough to shake all the nuts and bolts off the chassis.” The lesson: If you send music to a publisher which doesn’t work with your style, they’ll send it back.

[Publisher_3] is a big Christian music publisher, and works with many of the top artists. Consequently, they don’t have any more publication slots for new people.

Finally, [Publisher_4] labors under the same difficulties as other publishers, but in this example they also aren’t really interested in paying thousands of dollars in return postage for music they don’t want. Every publisher receives thousands of packages each year, if not each month, and must keep the profit assumption in mind if he’s to stay alive. So many publishers will acknowledge receipt of your music, tell you that they can’t accept it, and further say that “your music will be kept in file for six months, after which time it will be discarded; should you wish us to return your music, please send $x.xx to cover return postage.”

The main lesson to remember is that you shouldn’t take rejection letters personally. They’re usually written in a bland, sterile fashion so as to prevent arguments between composer and publisher. They won’t tell you why they don’t want your music because there are a lot of people out there who will take exception to the publisher’s decision and will start writing letters to argue with them. You’ll also find that they’re short; an economy of words also provides less fuel for the feisty. Consequently, publishers take this approach to keep things under control.

Don’t be offended if a publisher sends you a form letter (although I’m bothered by a certain publisher which has sent me ugly, streaky, grainy xeroxes of their standard rejection notice). Remember, each of them receives thousands of pieces seeking a publishing home, and therefore expediency dictates that a personal reply to each letter is impossible.

Side note: Some publishers are better at this game than others. The best ones send letters which turn you down while offering “best wishes as you attempt to place your work with another publisher.” The really good ones also probably have their “no thanks” letter in a word processor with blanks for your name, address, and composition title so that they can zap off a fresh laser printer copy which looks like it was made specially for you (well, it was, wasn’t it?). It’s the little extra touches that matter, and the publishers who are good at making rejection a gentler experience for you are the ones who will probably see your next attempt at composition. I’m sure that they think that if you’re given enough time and try enough times, you’ll send them something that they’ll want to use – you can only get better!

(The actual publishers’ names were excised to protect… me, I think.)

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12

Part 12

There are some ideas to consider when you’re looking for a publisher. The prime one is to try to establish a match between your composition and the publisher’s catalog. For instance, Lillenas anthems tend to be a little easier for the singers and accompanist, and stylistically are on the conservative side. Schirmer has a well-established bent toward purely classical music. Word has heavy leanings to the contemporary side. Alexandria House is somewhere between Lillenas and Word. Picking the right publisher will improve your chances substantially.

Small publishers can be good choices because they don’t necessarily have the wherewithal to procure the services of the big guns in the industry. Because of this, then, they need to call on lesser-known people – that’s you and me! You can obtain a list of publishers from the Church Music Publisher’s Association, P.O. Box 158992, Nashville, Tennessee 37215 (send $2.00 and an SASE, requesting their list of Church Music Copyright Holders).

Send a tape of your piece with [a copy of] your manuscript. It’s much quicker for the person who reviews your music if he/she can pop a tape into a cassette player and hear it. Remember, people in general make life easy for those who make life easy for them, and publishers are no exception. A good point which Brad Schield made concerning the quality of your tape is that it reflects the amount of care you take in your composing endeavors – make it the best you can!

Send your composition to more than one publisher at once. It takes about a month for someone to review a package, presumably because of existing backlog, so you might as well wait for only one month for a bunch of people simultaneously than to wait for each one singly. I know that some publishers don’t really want to review something which someone else is reviewing, but the practical consideration is that if you write something so good that more than one publisher wants it, then take the first offer you get and tell the other publisher that you’ve decided to decline his offer (without saying why). If this sounds rude and crass, I should tell you that this is advice I received from Fred Bock… his rationale is that life is too short!

Don’t forget your return envelope (with postage) unless you don’t care about getting your music back. Some publishers will return it anyway, but postal rates are so high that there aren’t many who will do this.

Do bear in mind that even if you’re writing great songs, having one published is largely a result of being in the right place at the right time (colloquialism: “dumb luck;” doctrinal orthodoxy: “fortuitous predestination”). It has to be a match between a submission to a publisher and a need to fill in the publishing schedule, or at least finding someone who’s willing to put in a good word to encourage the publisher to take that chance on your behalf.

One more word: this is not an impossible dream! As I wrote earlier, I had the opportunity to meet and talk with Fred Bock a couple of summers ago. It was a great learning experience. At his workshop, we had the opportunity to share our compositions with each other: I played a tape of “Praise His Name Forevermore,” which has been done at Valley Church three times (SSA, SATB, and trumpet trio), and got a lot of good feedback. Fred said that it was a lot better than most stuff that crosses his desk.

This motivated me to assemble a package for Fred a couple of weeks later. I sent it and waited for word. One month passed… two months… and finally, Fred sent a letter back explaining that he hadn’t had a lot of time to review music, and that he was finally getting around to it and that he was interested in publishing not just one, but two of the pieces I’d sent – PTL! I signed the contracts, and was hoping that the pieces would be released in 1992, but the recession forced Fred to reduce his publication list – and my pieces were two of the amputees. C’est la vie…