Francis Scott Key wrote the words for “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1814 after seeing the American flag raised over Fort McHenry in celebration of victory. The modern rendition (most often at patriotic and sports events, with biennial playings at the Olympics) usually consists of just Key’s first verse. All four of his verses, as kept in the National Museum of American History, are below.

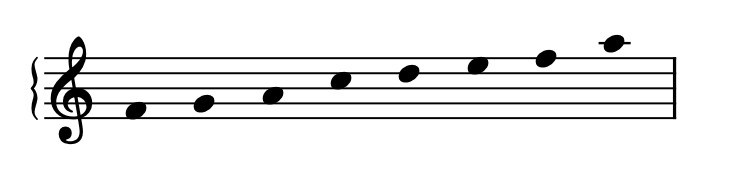

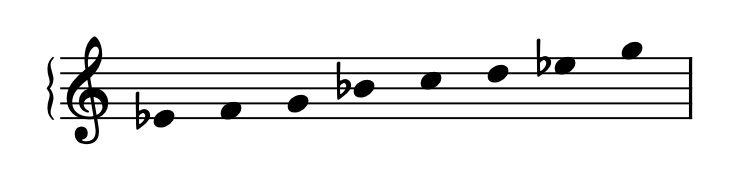

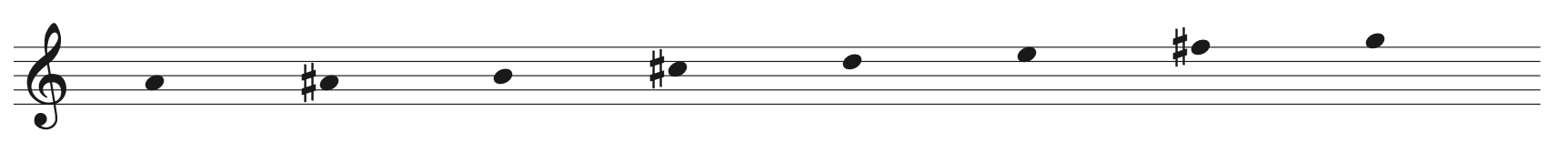

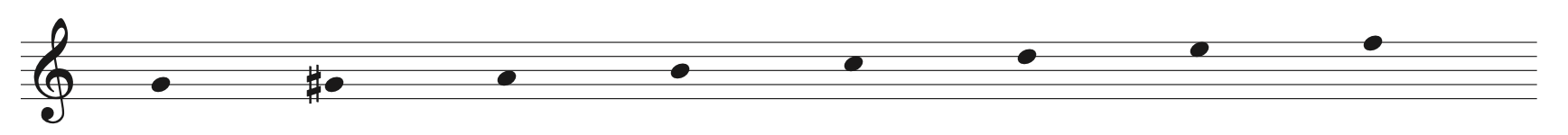

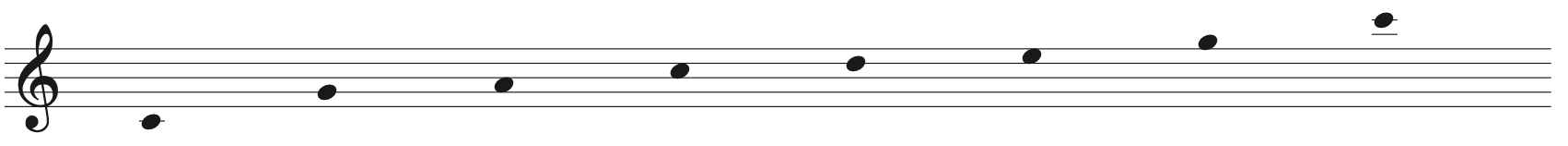

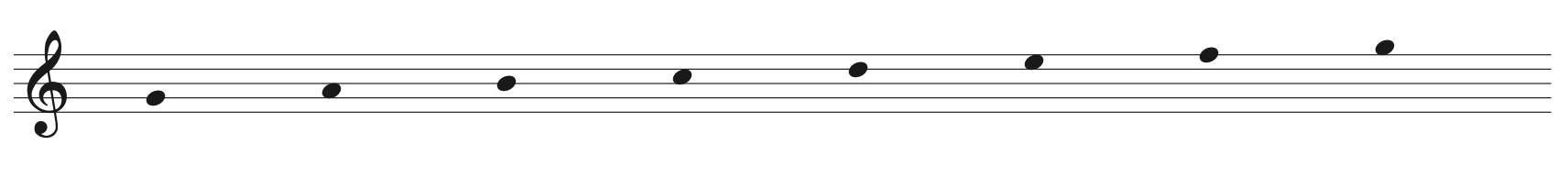

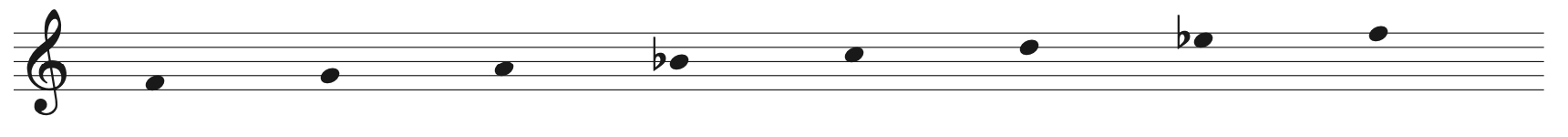

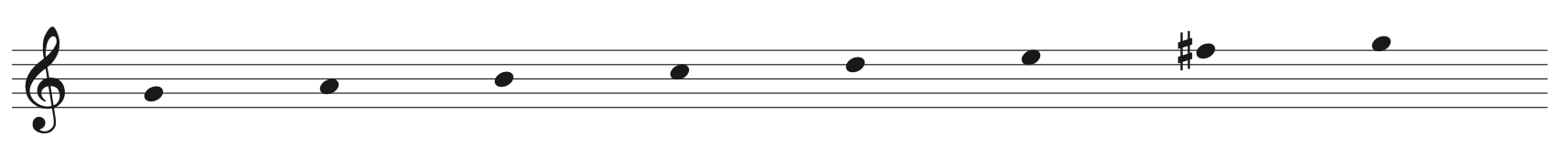

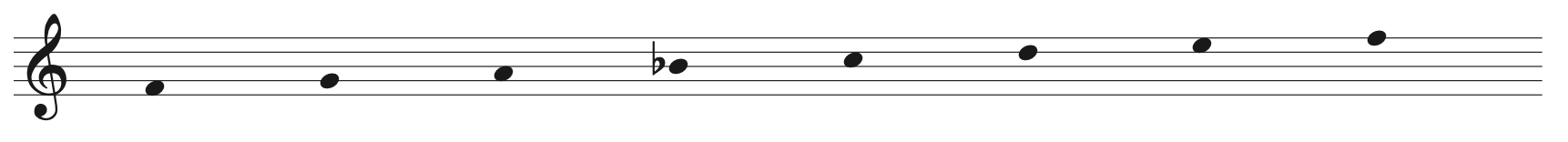

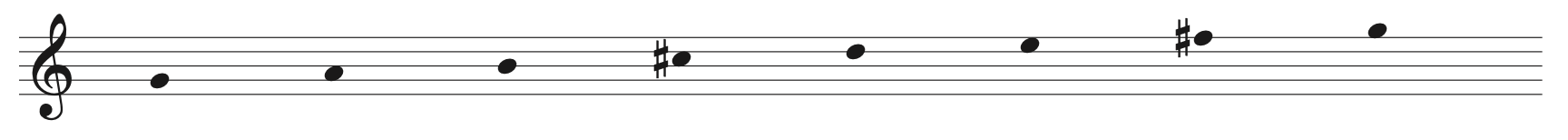

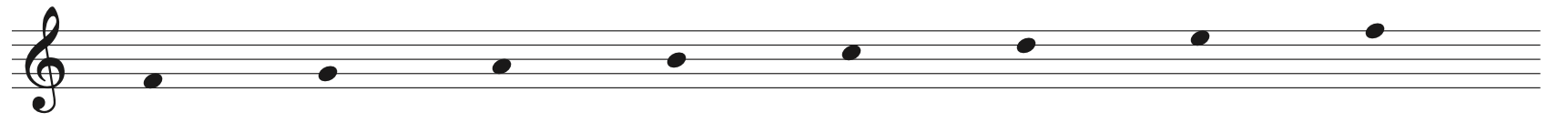

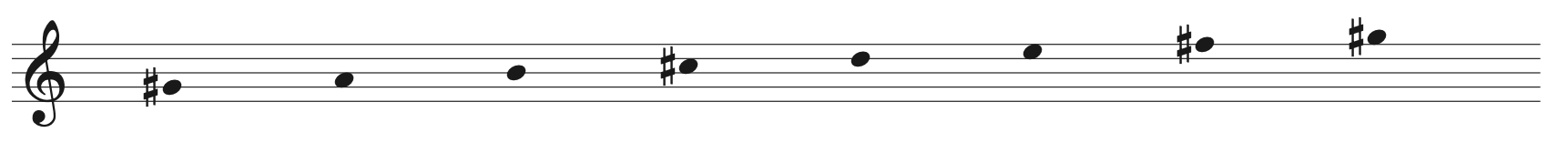

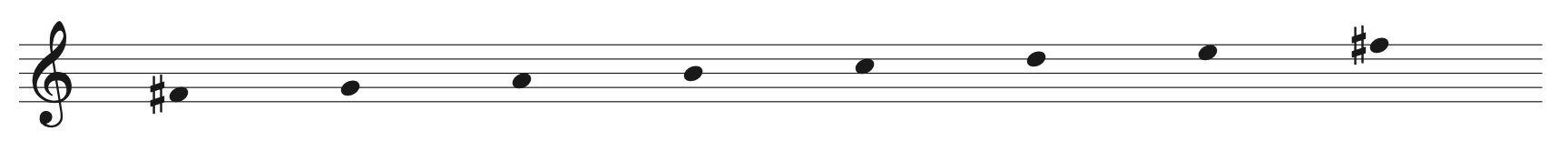

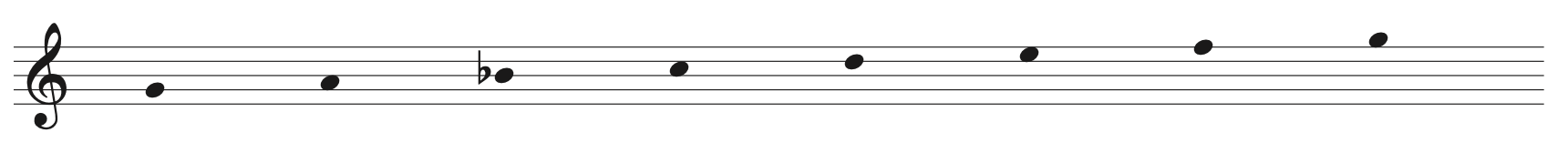

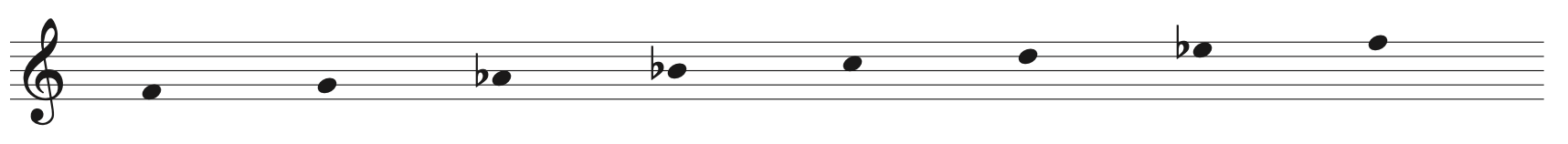

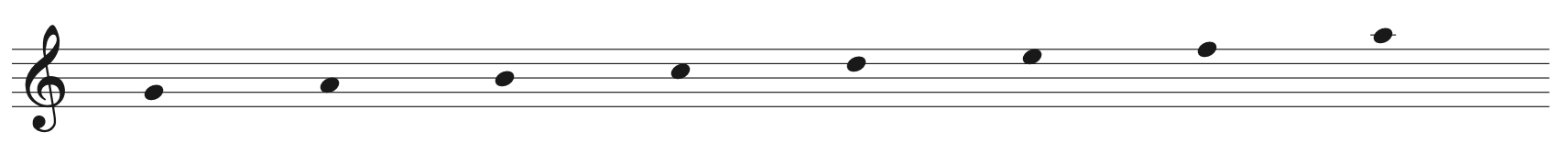

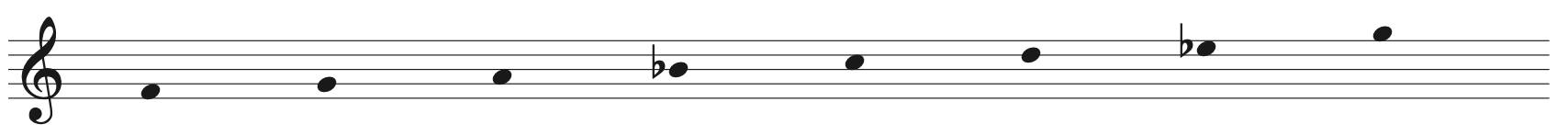

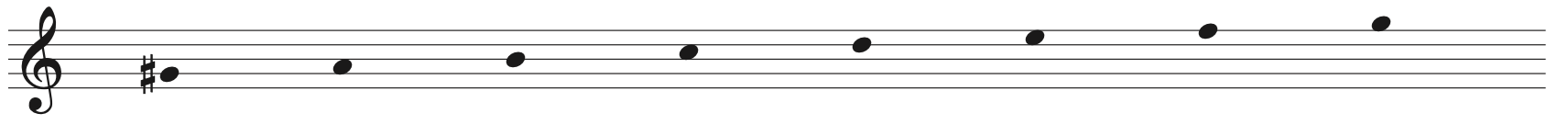

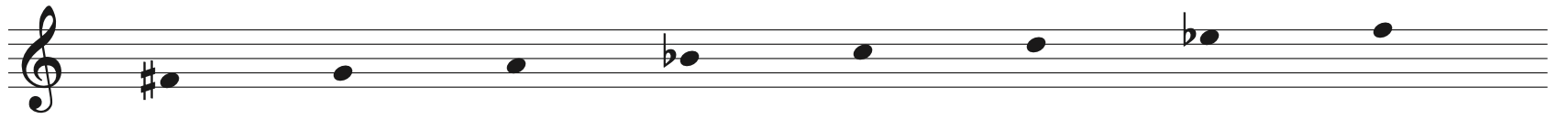

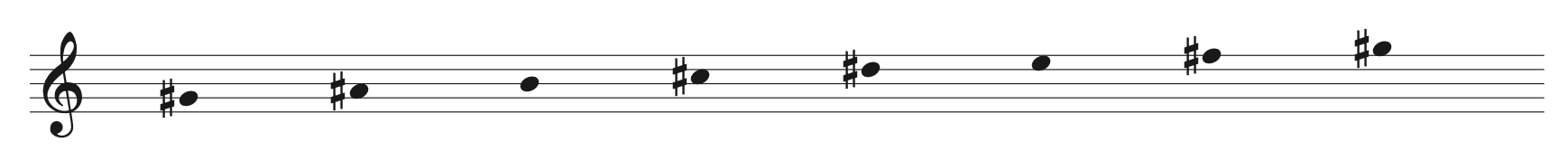

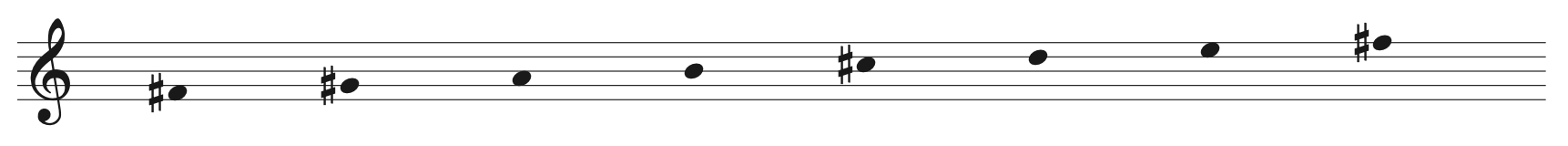

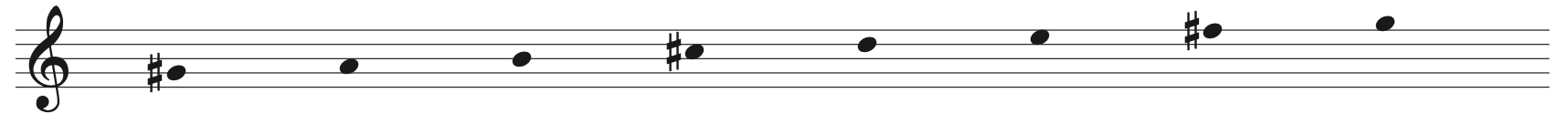

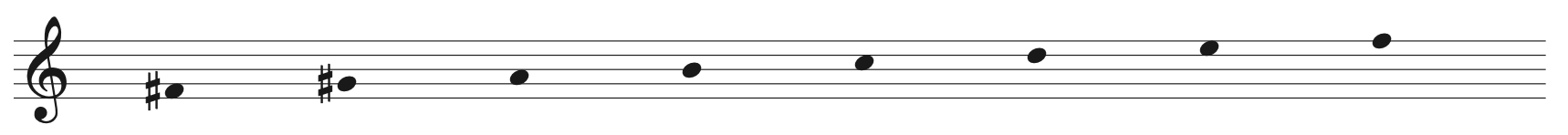

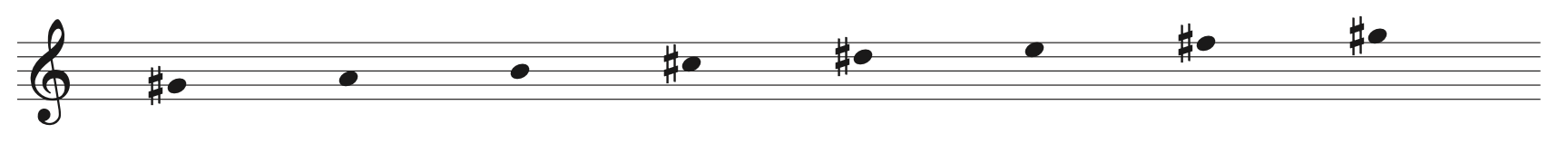

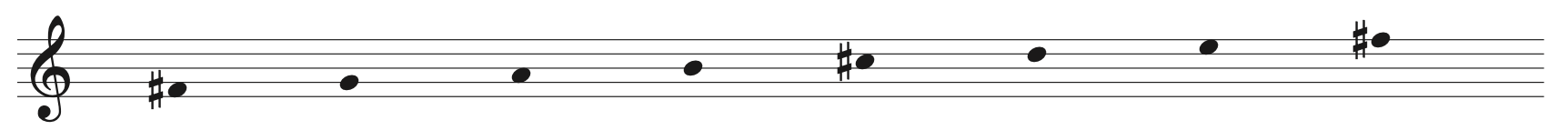

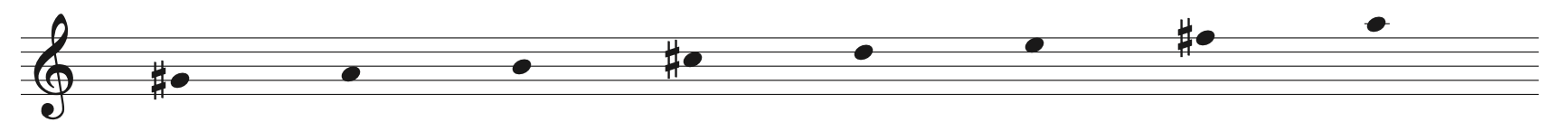

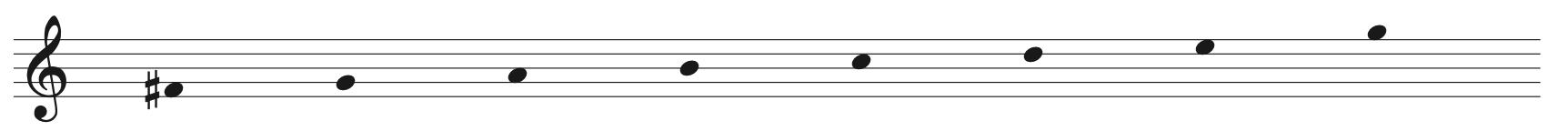

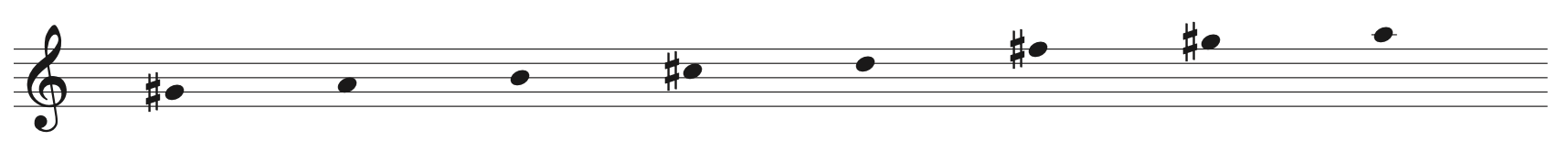

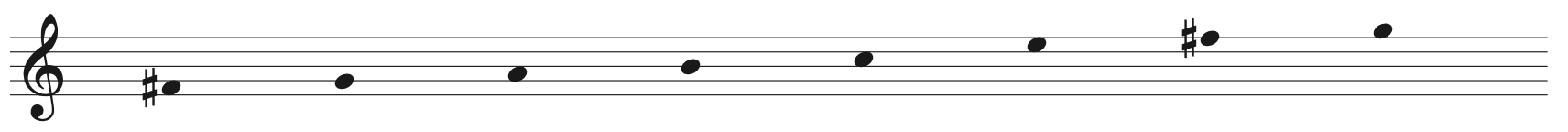

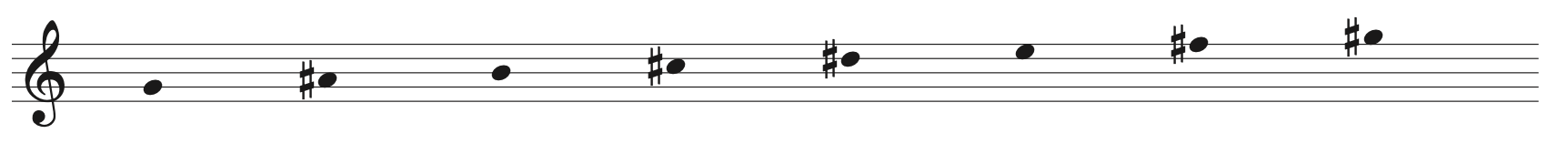

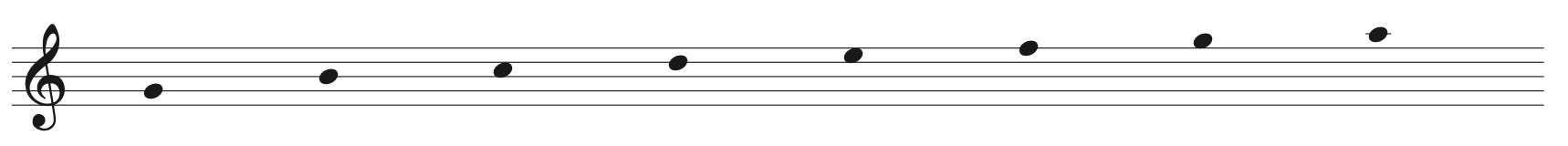

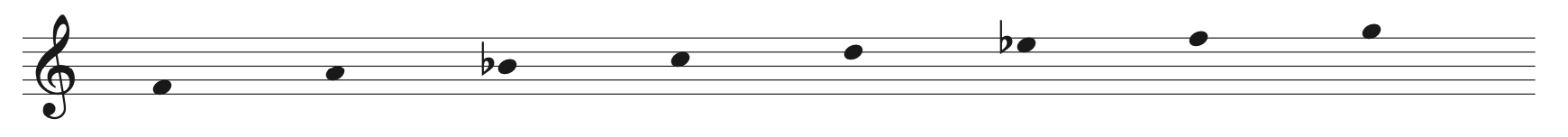

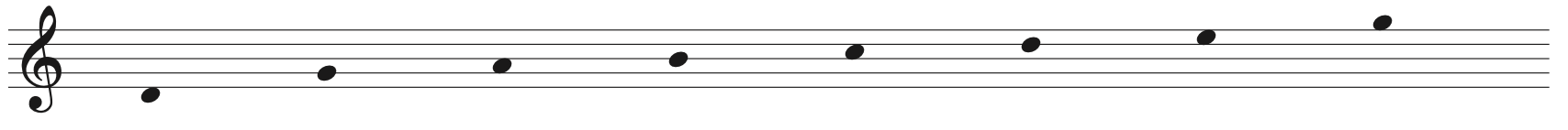

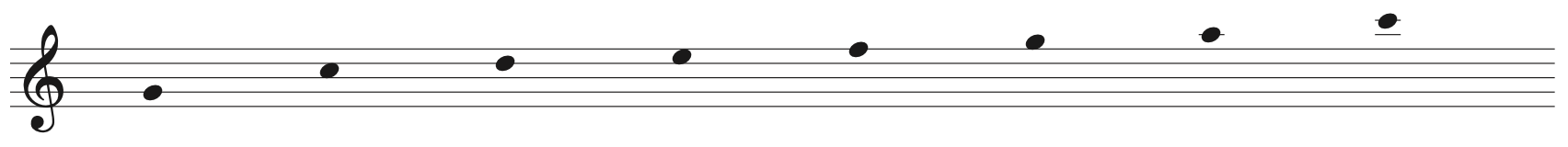

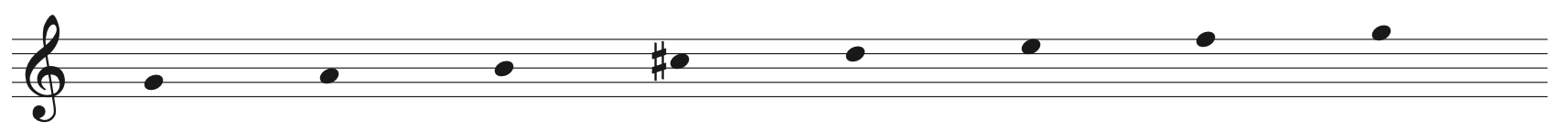

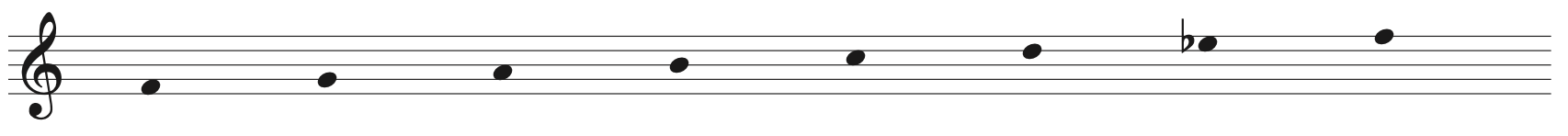

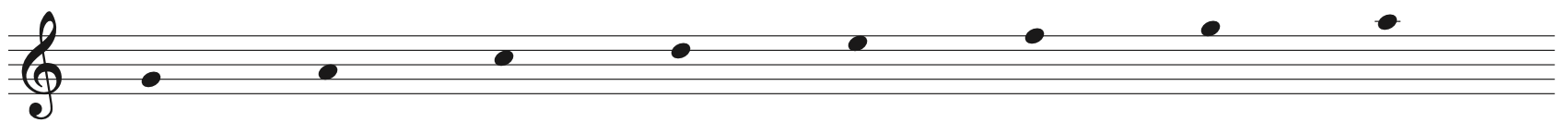

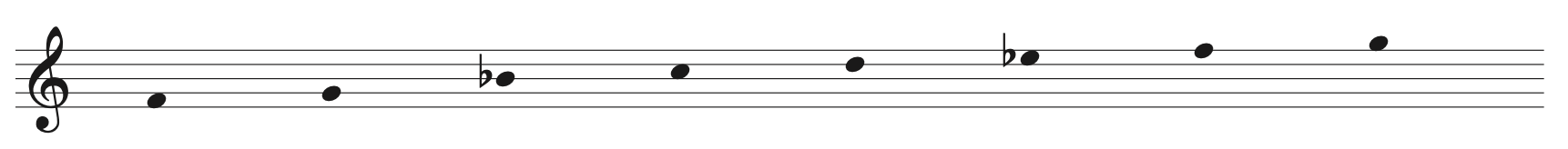

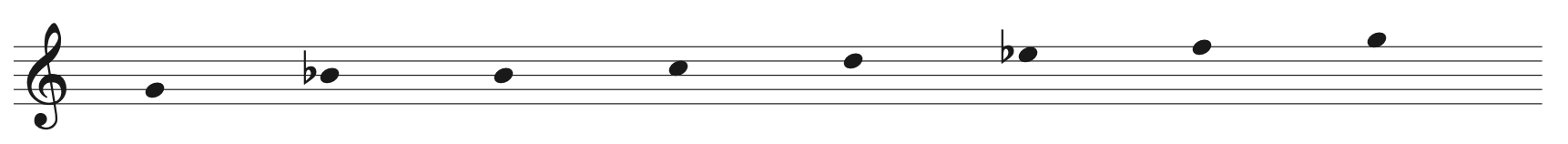

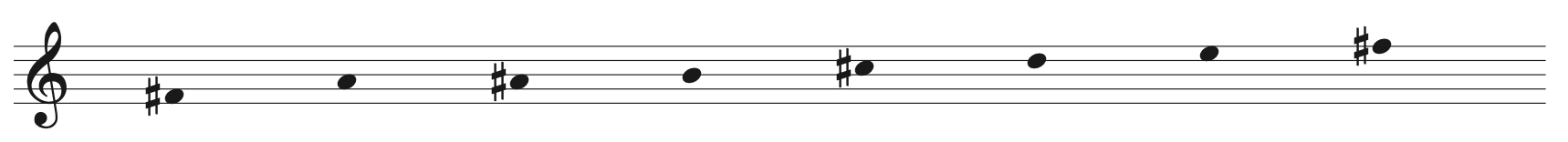

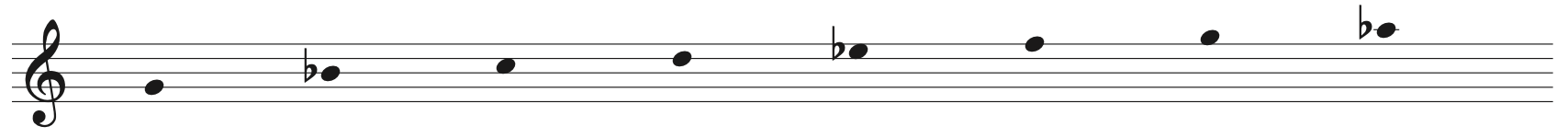

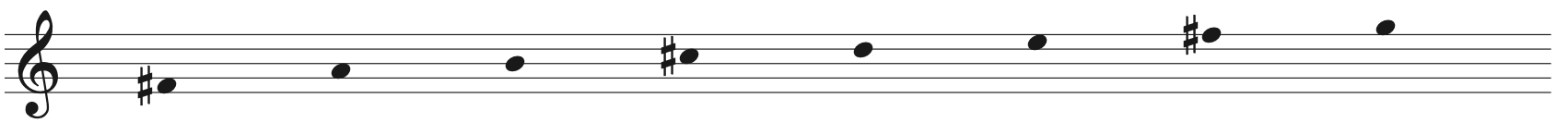

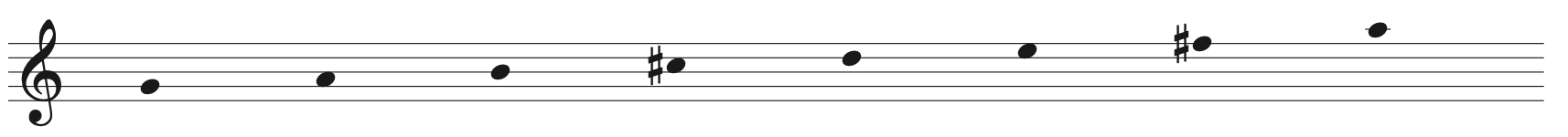

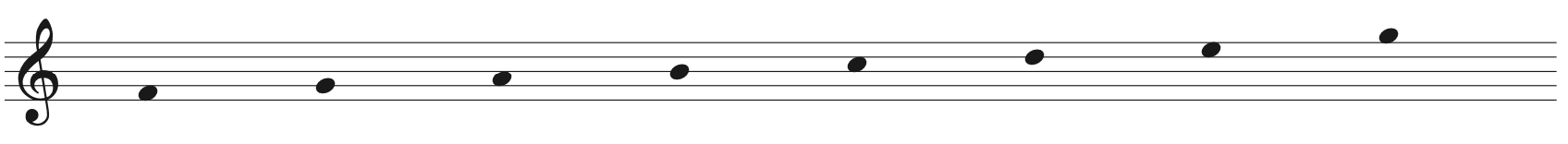

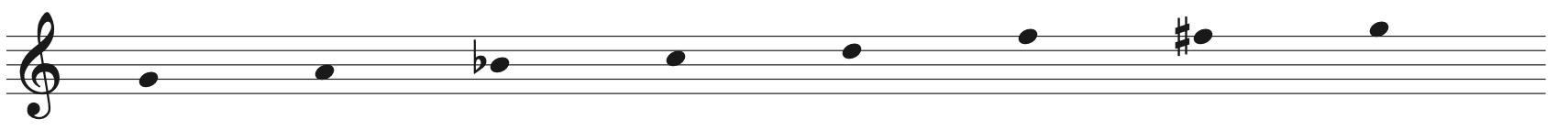

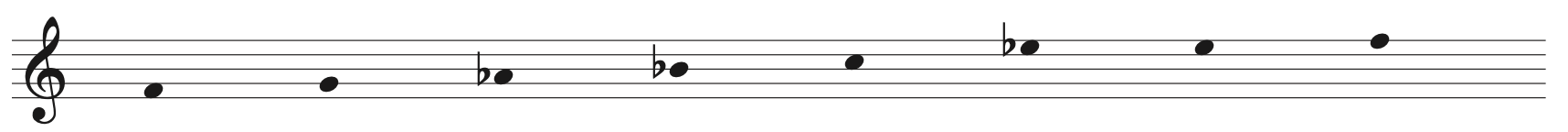

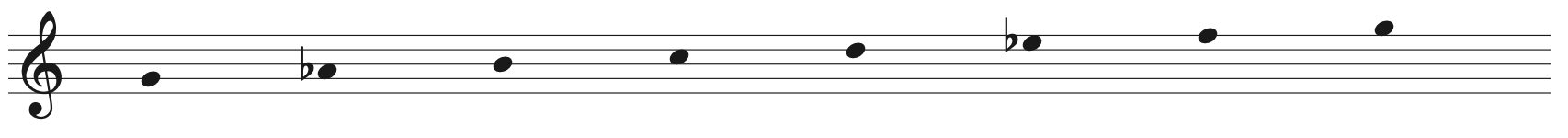

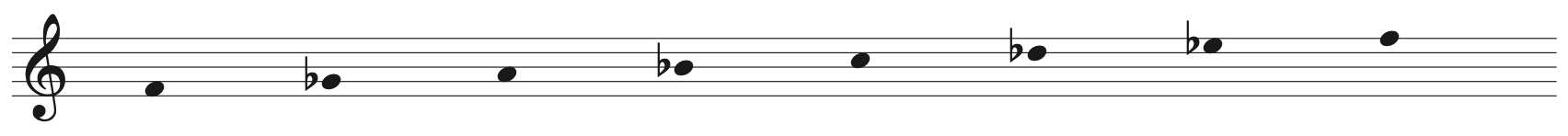

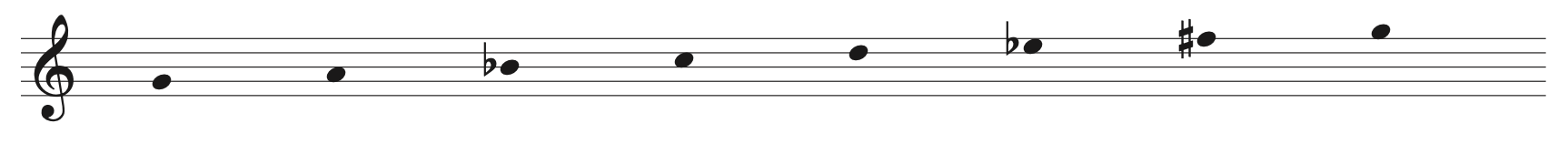

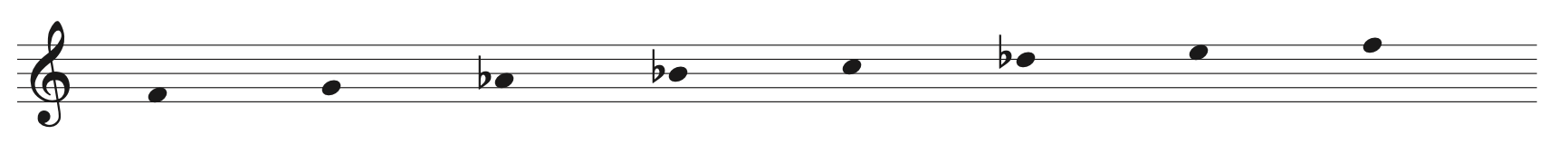

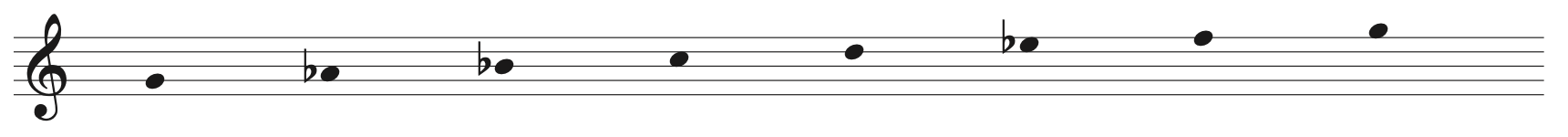

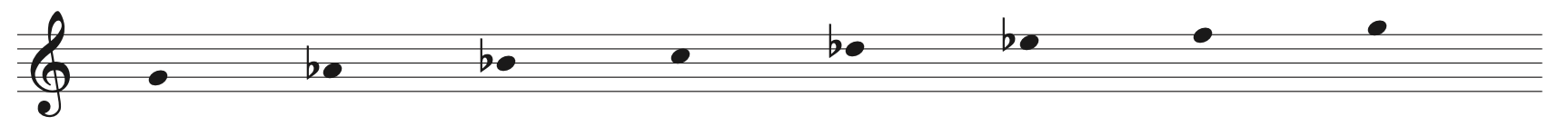

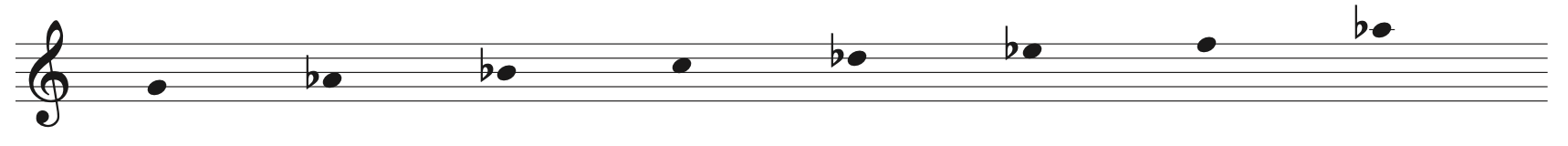

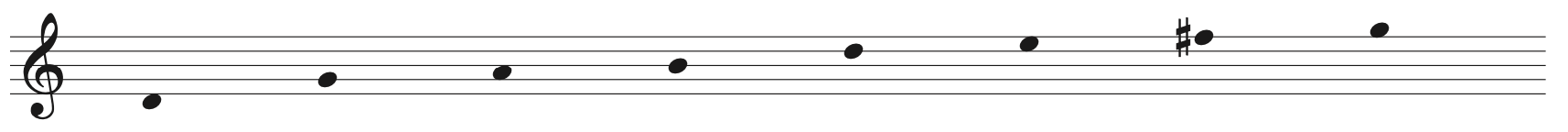

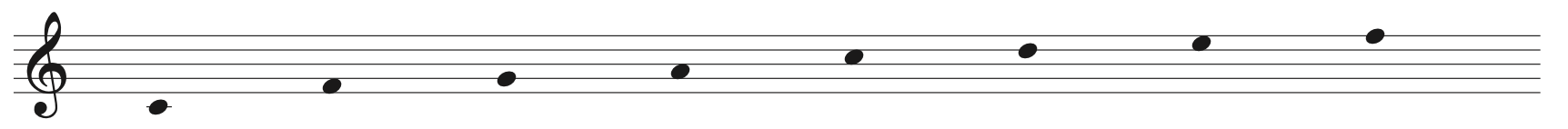

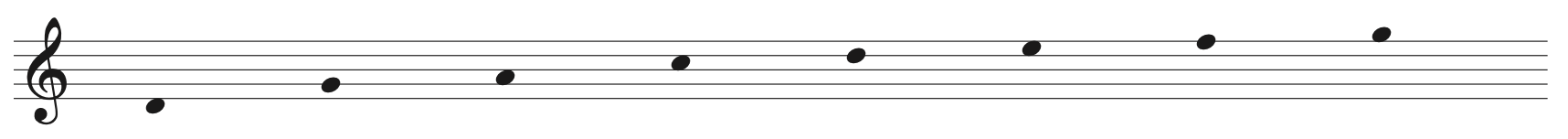

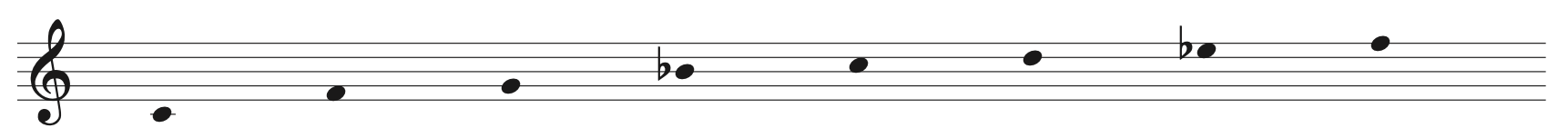

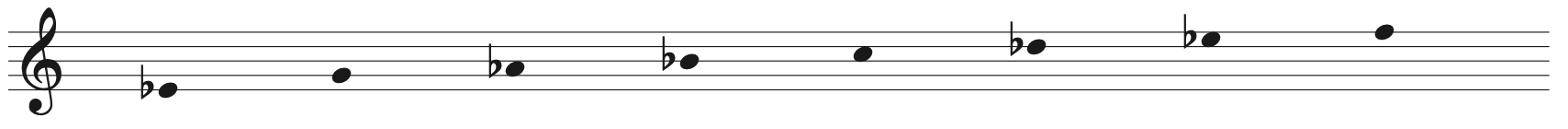

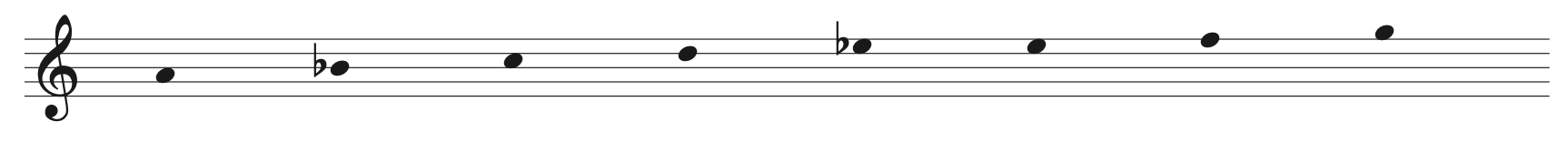

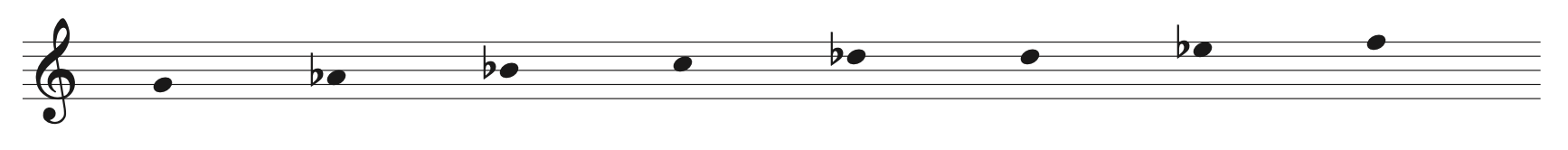

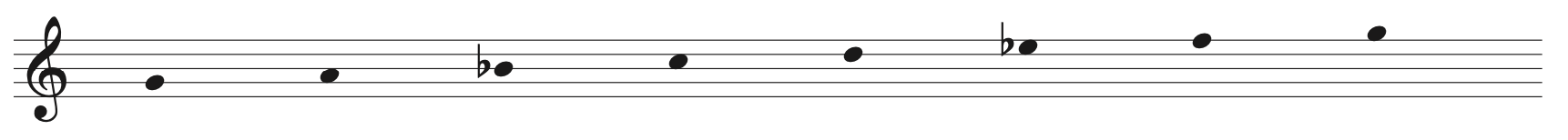

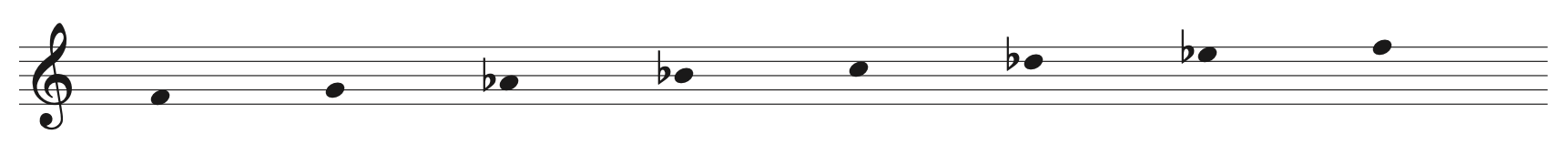

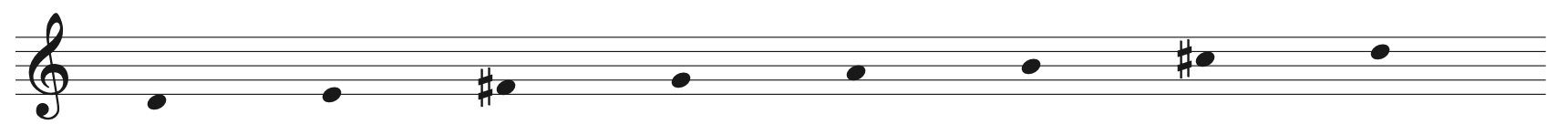

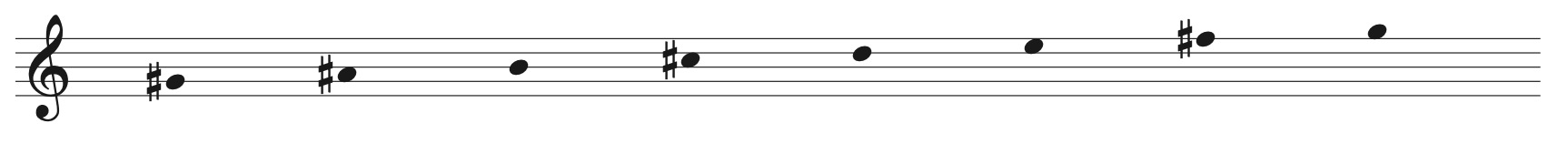

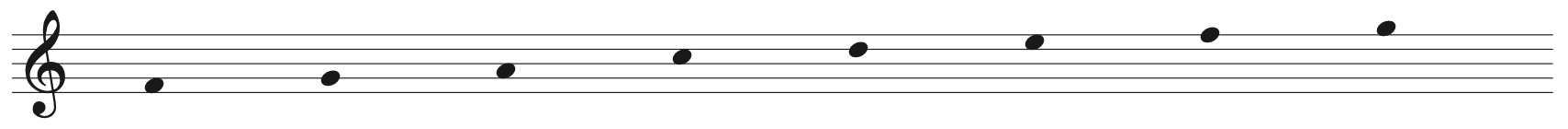

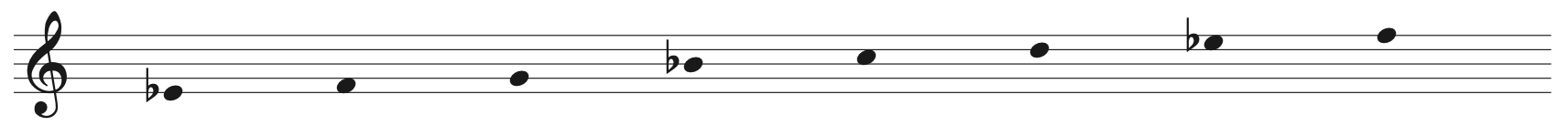

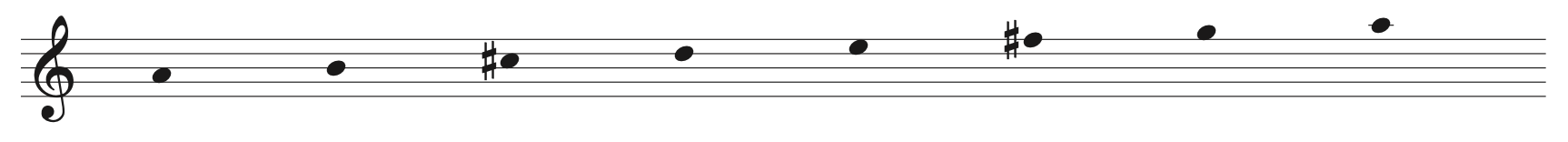

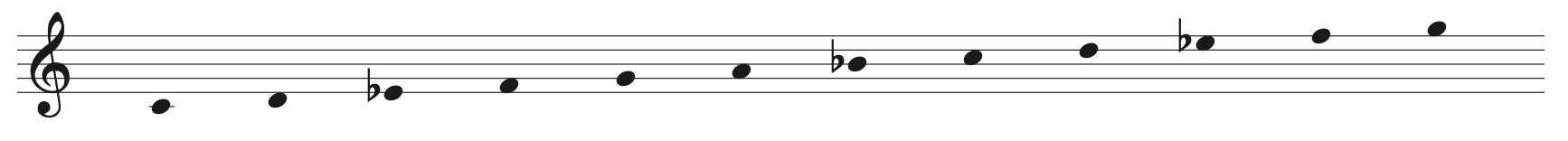

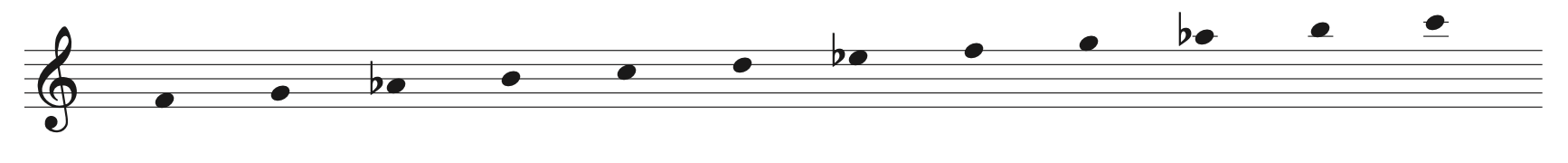

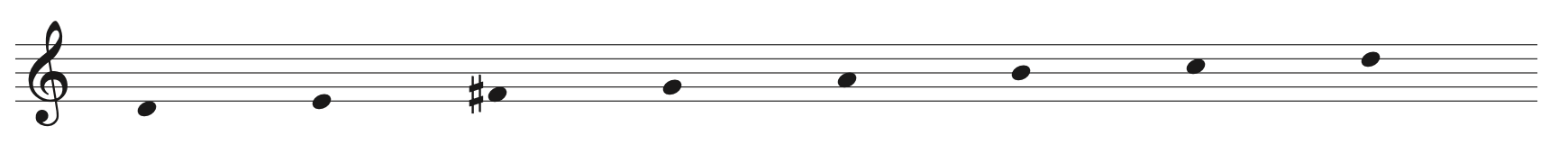

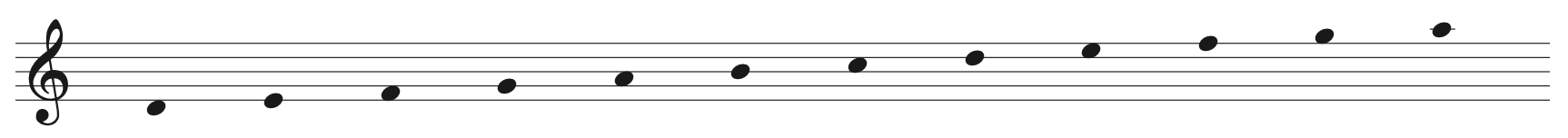

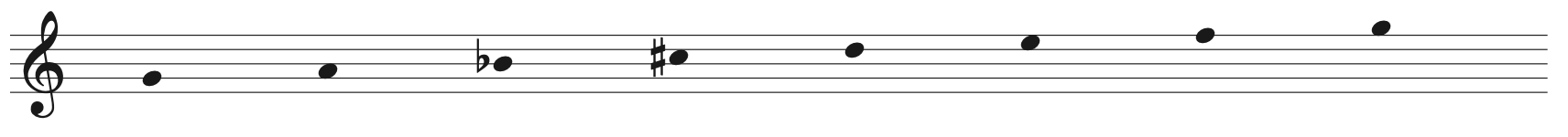

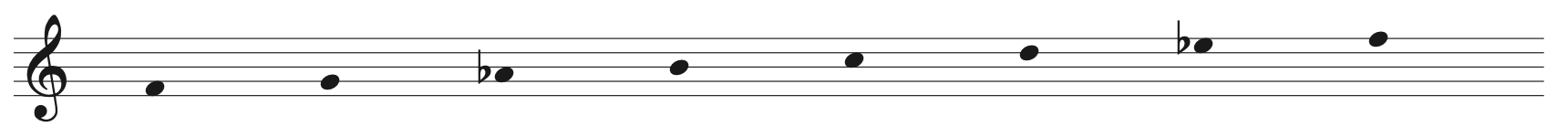

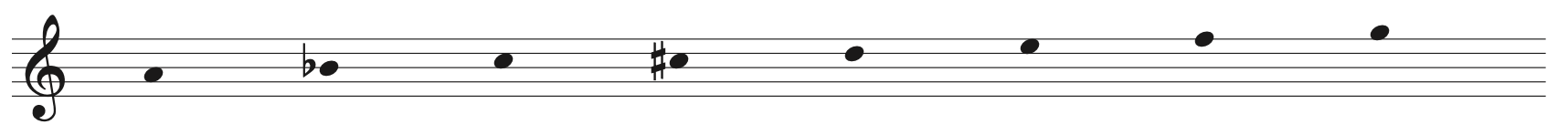

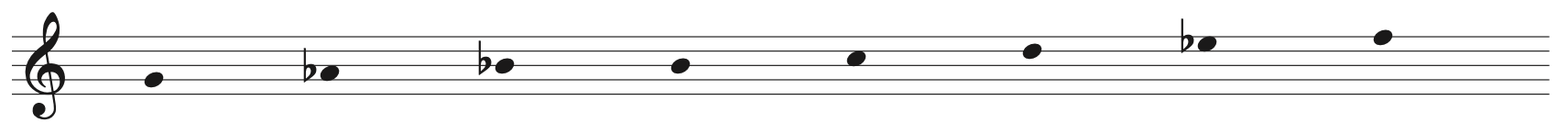

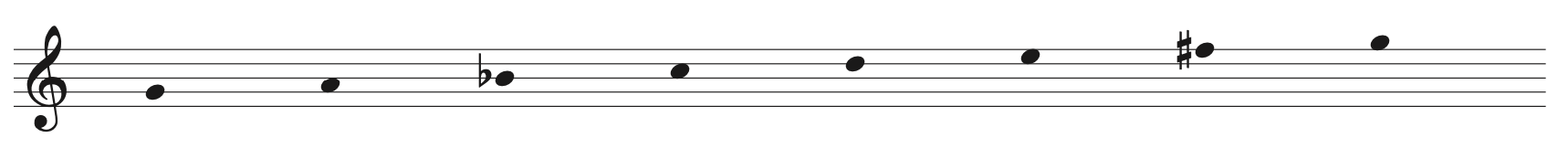

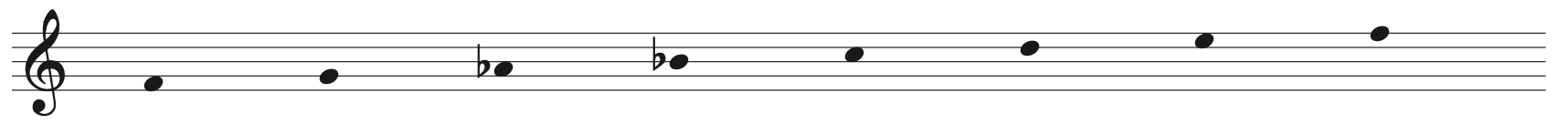

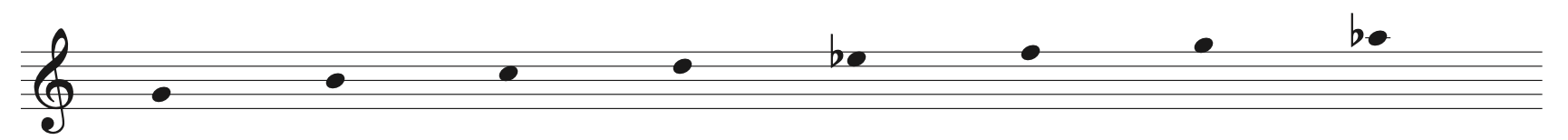

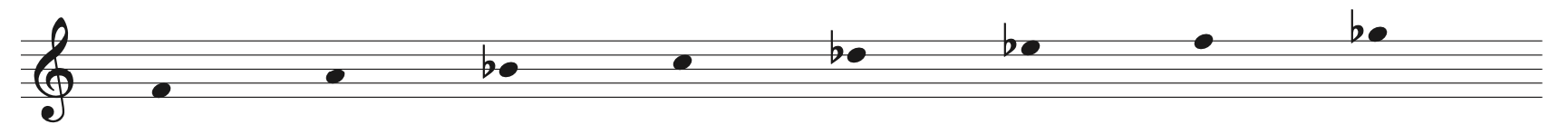

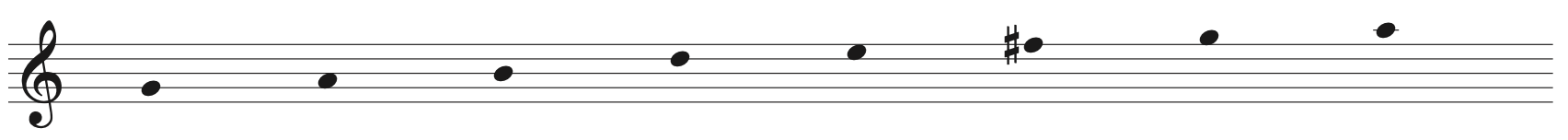

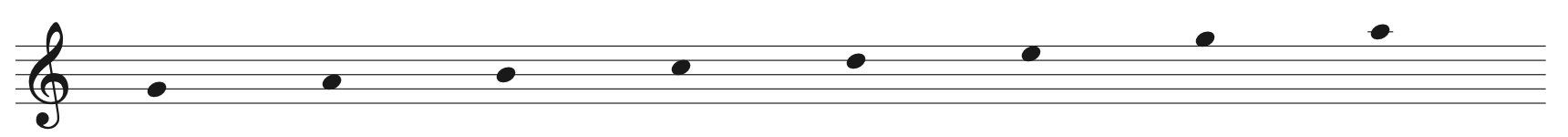

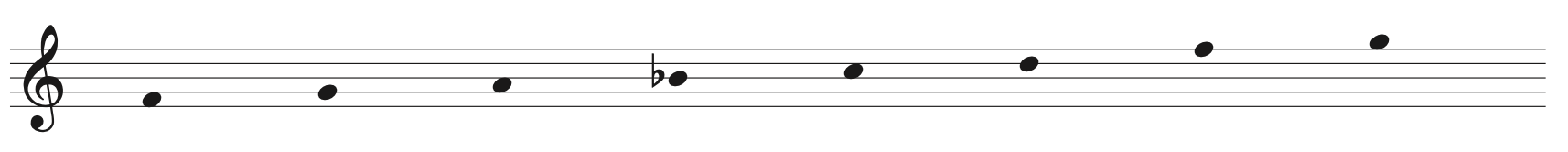

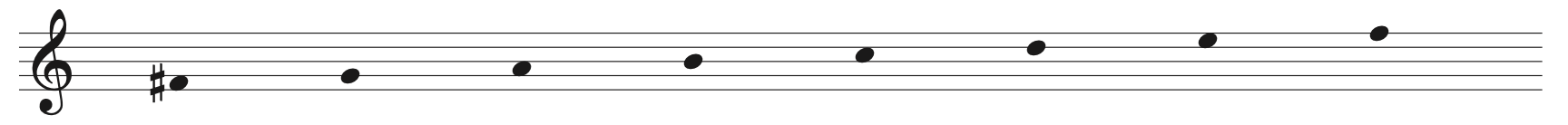

Rather curiously, Americans sing their national anthem to the British song “To Anacreon in Heaven” by John Stafford Smith. The melody tests the vocal range of even the best singers, spanning twelve scale tones.

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bomb bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream,

‘Tis the star-spangled banner – O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a Country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O thus be it ever when freemen shall stand

Between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto – “In God is our trust,”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

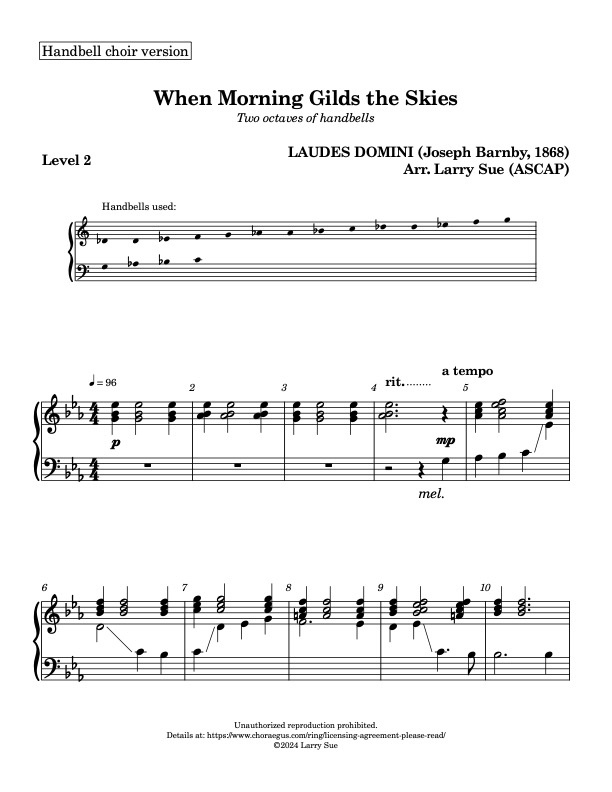

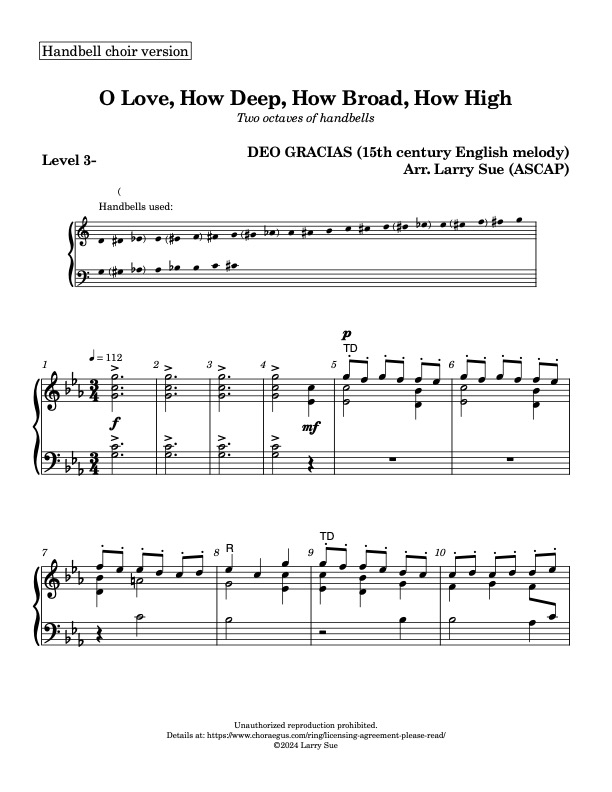

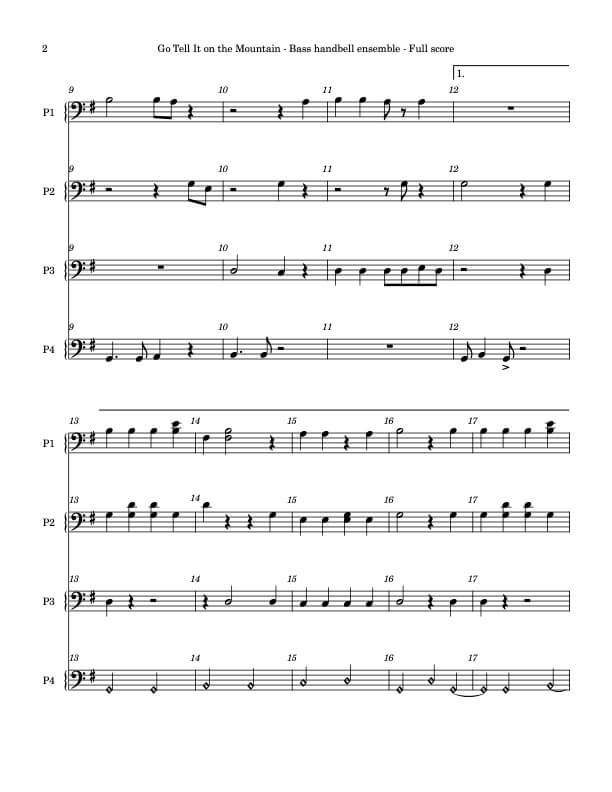

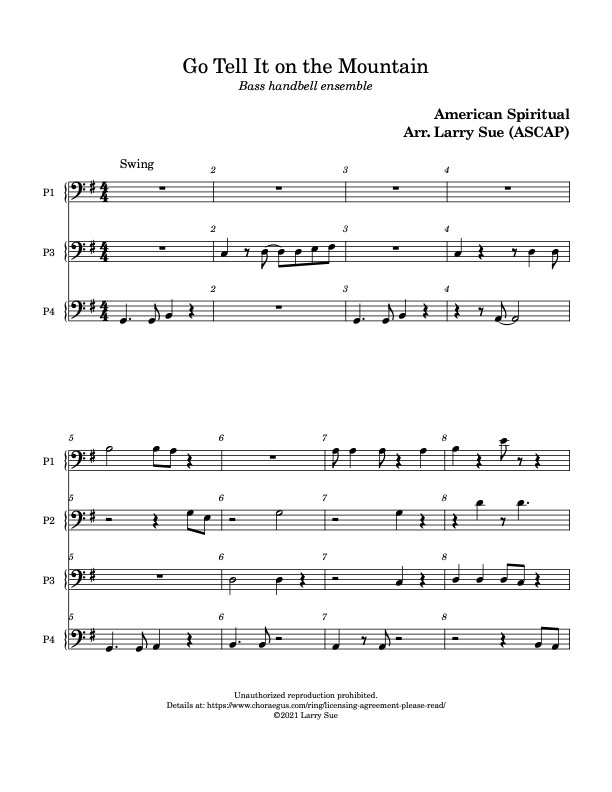

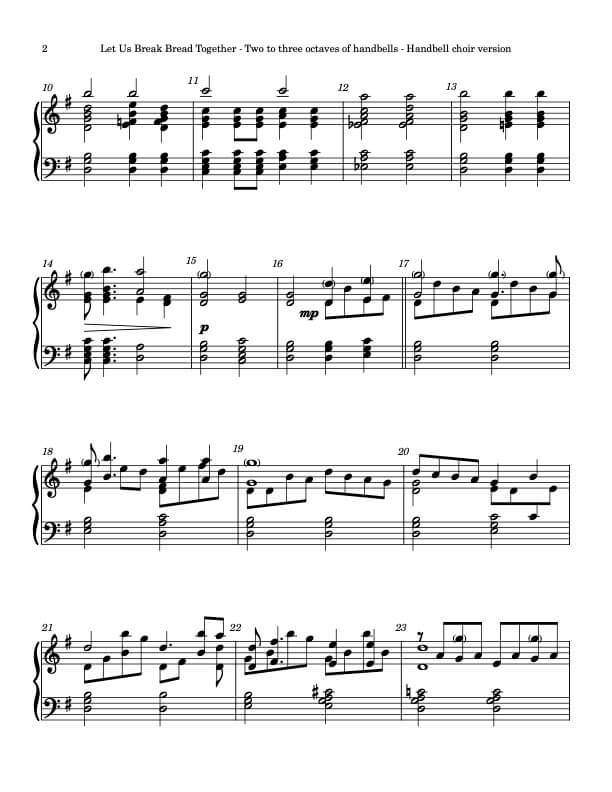

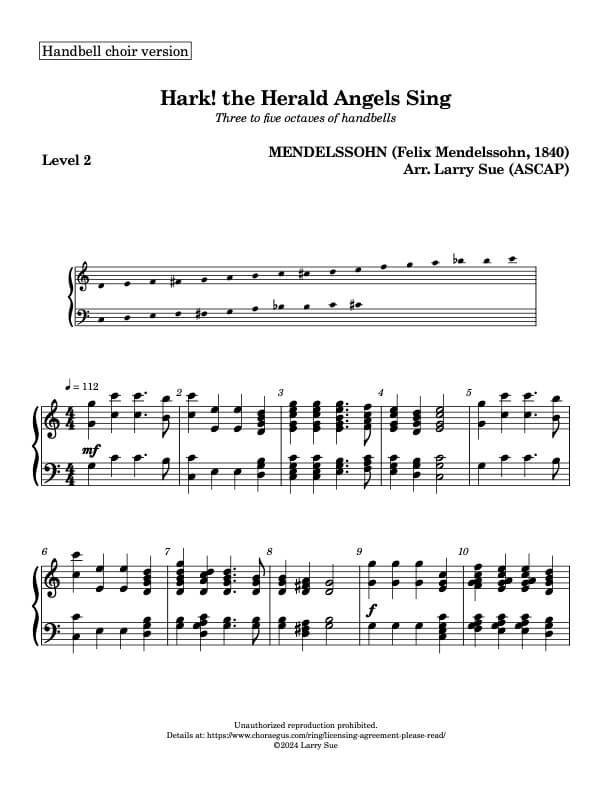

Purchasing this 12-bell arrangement gives you permission to print and maintain up to six copies for your handbell group – so you only need to pay once. Purchase also gives permission for performance, broadcasting, live-streaming and video-sharing online. See our licensing agreement for full details, and please remember to mention the title and arranger of the piece on video-sharing sites, social media and any printed materials such as concert programs.